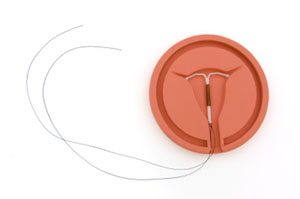

Even though they’re more effective at preventing pregnancy than most other forms of contraception, long-acting birth-control methods such as intrauterine devices and hormonal implants have been a tough sell for women, especially younger ones. But changes in health-care laws and the introduction of the first new IUD in 12 years may make these methods more attractive. Increased interest in the devices could benefit younger women because of their high rates of unintended pregnancy, according to experts in women’s reproductive health.

IUDs and the hormonal implant — a matchstick-sized rod that is inserted under the skin of the arm that releases pregnancy-preventing hormones for up to three years — generally cost between $400 and $1,000. The steep upfront cost has deterred many women from trying them, women’s health advocates say, even though they are cost-effective in the long run compared with other methods, because they last far longer.

Under the Affordable Care Act, new plans or those that lose their grandfathered status are required to provide a range of preventive benefits, including birth control, without patient cost-sharing. Yet even when insurance is covering the cost of the device and insertion, some plans may require women to pick up related expenses, such as lab charges.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs) require no effort once they’re put into place, so they can be an appealing birth-control option for teens and young women, whose rates of unintended pregnancy are highest, experts say.

Across all age groups, nearly half of pregnancies are unintended, but younger women’s rates are significantly higher, according to a 2011 study from the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive health research organization. Eighty-two percent of pregnancies among 15- to 19-year-olds were unintended in 2006, and 64 percent of those among young women age 20 to 24 were unintended, the study found.

Although the use of LARCs has more than doubled in recent years, it is a small part of the contraceptive market. Among women who use birth control, 8.5 percent of women used one of those methods in 2009, according to the Guttmacher Institute. The use of LARCs by teenagers was significantly lower at 4.5 percent, while 8.3 percent of 20- to 24-year-olds chose this type of contraception.

In October, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reiterated its strong support for the use of LARCs in young women.

Yet many young women are unaware that long-acting methods could be good options for them, in part because their doctors may be reluctant to prescribe them, experts say. That is partly the legacy of the Dalkon Shield, an IUD that was introduced in the 1970s whose serious defects caused pain, bleeding, perforations in the uterus and sterility among some users. The problems led to litigation that resulted in nearly $3 billion in payments to more than 200,000 women.

In addition, providers may hesitate because there’s a slightly higher risk that younger women will expel the device, experts say.

But expulsion is a problem more likely associated with the size of the uterus, which is not necessarily related to a patient’s age, says Tina Raine-Bennett, research director at the Women’s Health Research Institute at Kaiser Permanente Northern California and chairwoman of the ACOG committee that released the revised opinion on LARCs. “Expulsion is only a problem if it goes unrecognized.” (Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

The new IUD Skyla became available in mid-February. It is made by Bayer, the same company that makes Mirena, another IUD sold in the United States. Unlike Mirena, which is recommended for women who have had a child, Skyla has no such restrictions (nor does ParaGard, the third type of IUD sold here). Mirena is currently the subject of numerous lawsuits alleging some complications, such as device dislocation and expulsion.

Skyla is slightly smaller than the other two IUDs on the market and is designed to protect against pregnancy for up to three years, a shorter time frame than the others.

This shorter time frame may make Skyla more attractive to younger women who think they may want to get pregnant relatively soon, some experts say, although any IUD can be removed at any time.

“More providers are spreading the word that it’s okay, and more young women are demanding it,” says Eve Espey, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of New Mexico.

This article was produced by Kaiser Health News with support from The SCAN Foundation.

Please send comments or ideas for future topics for the Insuring Your Health column to questions@kffhealthnews.org.