The coronavirus pandemic is now stretching into its third year, a grim milestone that calls for another look at the human toll of covid-19, and the unsteady progress in containing it.

The charts below tell various aspects of the story, from the deadly force of the disease and its disparate impact to the signs of political polarization and the United States’ struggle to marshal an effective response.

Covid rocketed up the list of leading killers in the U.S. like nothing in recent memory. The closest analogue was HIV and AIDS, which ranked among the top 10 causes of death from 1990 to 1996. But even HIV/AIDS never reached higher than eighth on that list.

By contrast, covid shot up to third in 2020, its first year of existence, covering only about nine months of the pandemic. Only heart disease and cancer killed more Americans that year.

“The leading causes of death are relatively stable over long periods of time, so this is a very striking result,” said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and health policy at Vanderbilt University.

Covid generally hit people of color harder, a pattern experts trace back to historical disparities in income, geography, medical access, and educational attainment.

“This tells us something about our society — it’s a kind report card,” Schaffner said. Studies have shown that illness and prevention are even more strongly correlated with educational background than with income.

“There was some effort to correct the disparities,” said Arthur Caplan, a professor of bioethics at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine. “But these were band-aids on a system that remains broken.”

Older people tend to be more vulnerable to disease than younger people, because of weaker immune systems and underlying health problems. That’s been especially true with covid.

“Many other infections affect the very young and the very old disproportionately, but covid-19 stands out in being so age-dependent,” said Dr. Monica Gandhi, a professor of medicine at the University of California-San Francisco. “Children were remarkably spared from severe disease in the U.S., as they were worldwide.”

Deaths among older Americans, however, were especially widespread in the early days of the pandemic due to the close contact of seniors living in nursing homes.

“Some will argue that [the] old are frail anyway, but I find that morally repugnant,” Caplan said. The deaths of so many older people “makes me extremely sad.”

The good news, experts say, is that older Americans were the most likely to get vaccinated, with a 91% full vaccination rate for those between ages 65 and 74. This almost certainly prevented many deaths among older people as the pandemic ground on, Schaffner said.

Although the pandemic has had its peaks and valleys, due to largely seasonal factors and the emergence of new variants, it has continued to produce deaths at a fairly steady rate since its beginning two years ago.

The pandemic is “impressive in how it just keeps going,” Schaffner said.

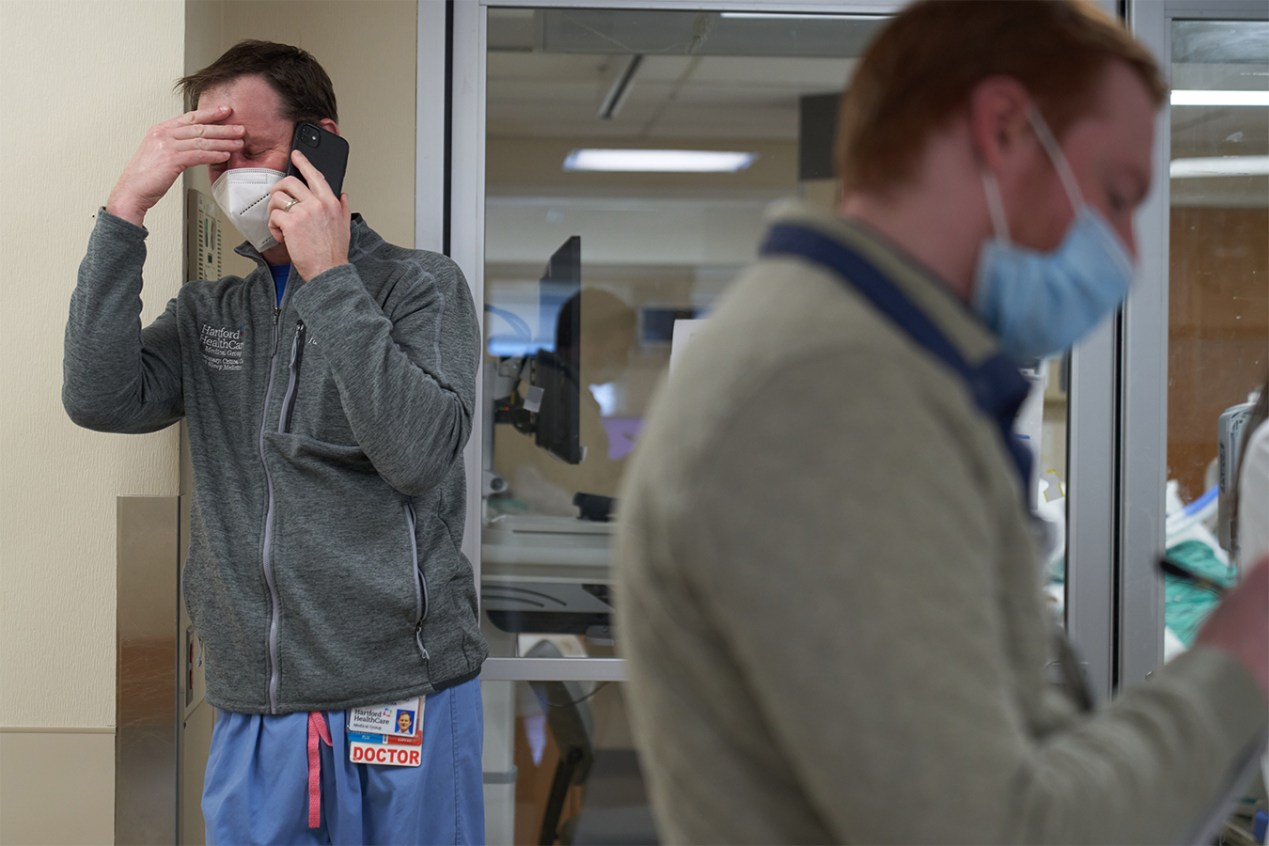

The slow grind is “why we’re exhausted,” Caplan said. “It’s like we can’t make a significant dent, no matter what we do.”

There have been five distinct peaks: the initial one in April 2020, a summer spike in August 2020, a winter spike in January 2021, the initial outbreak of the delta variant in September 2021, and the omicron surge in January 2022.

The on-off nature of the pandemic “has led to a lot of the confusion and grumpiness,” Schaffner said. Caplan compared it to the exhaustion of the American public when hearing body counts during the Vietnam War.

Once a natural disaster like a hurricane or a tornado has passed, Schaffner added, it’s gone and people can rebuild. With covid, it’s just been a matter of time before the next wave arrives. The coronavirus also affected the whole world, unlike a localized disaster.

Such factors “stretched the capacity of the public health system and our governance,” Schaffner said.

Not surprisingly, the number of deaths in each state was heavily dependent on the size of the state’s population. California and Texas each lost more than 80,000 people to covid, while Vermont lost 546.

But once you adjust for population, distinct differences emerge in how various states fared during the pandemic.

The seven states with the worst death rates include densely populated New Jersey, an affluent, educated Northeast state, and Arizona, a fairly diverse Southwestern state. The other five are Southern states that rank among the 11 states with the lowest levels of educational attainment and median income: Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee, and West Virginia.

Among the states with the lowest death rates, Hawaii and Alaska (and, to an extent, Vermont and Maine) are isolated and may have had an easier time keeping the virus out.

“For all the grumbling you hear about federal mandates and enforcement, you can’t help but look at this list and see that the pandemic has been handled state by state,” Caplan said.

The world’s performance in battling covid is analogous to the United States’: Some places did it well, and others did not.

And in the international context, the United States’ record was not so hot.

When comparing death rates around the world, it’s clear how much worse the U.S. has fared than other wealthy industrialized nations.

The countries that have a higher death rate than the U.S. are largely medium-size and middle-income. The industrialized Western nations that are the United States’ closest peers all managed to do better, including the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Canada.

Meanwhile, other affluent countries did far better than the U.S. did, including Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan (which have more experience with airborne diseases and greater public tolerance for masking), and two island nations: Australia and New Zealand.

In general, Schaffner said, countries that performed better than the U.S. tended to have “sustained, single-source, science-based communication. They communicated well with their populations and explained and justified why they were doing what they were doing.”

It’s impossible to look at the United States’ response to covid without factoring in the extent to which it became politicized. Almost from the beginning, basic communications about the severity of the disease and how to combat its spread broke down along partisan lines. The way Americans responded also followed a partisan pattern.

Most states that voted for Joe Biden for president in 2020 had above-average vaccination rates. Most states that voted for Donald Trump in 2020 had below-average rates.

Among the outliers in that pattern were Arizona, Nevada, Michigan, and Georgia, which supported Biden but had below-average vaccination rates. All four had very tight races in 2020; and Trump won three of them in 2016. The outliers on the other side were Florida and Utah, which supported Trump but had higher-than-average vaccination rates.

Efforts to promote vaccination as advancing the common good “got beaten back by arguments about autonomy and individual freedom,” Caplan said.

The rejection of vaccines by many Americans helped bring down U.S. vaccination rates compared with other countries as well.

The U.S. full-vaccination rate of just under 66% was higher than the world average of about 54%, but not especially impressive considering the United States’ wealth and the fact it was producing many of the key vaccines in the first place. Essentially every other high-income country has vaccinated a higher share of its residents than the U.S. has.

The fact that the United States has both a lower rate of full vaccination and a higher death rate than other high-income countries “makes me wonder how we might have done as a country if our pandemic response had not been so politicized and polarized,” said Brooke Nichols, an infectious-disease mathematical modeler at Boston University.