It’s remarkable that the reputation of the National Institutes of Health has remained mostly intact through the covid-19 pandemic, even as other federal science agencies, including the Food and Drug Administration and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, have come under partisan fire.

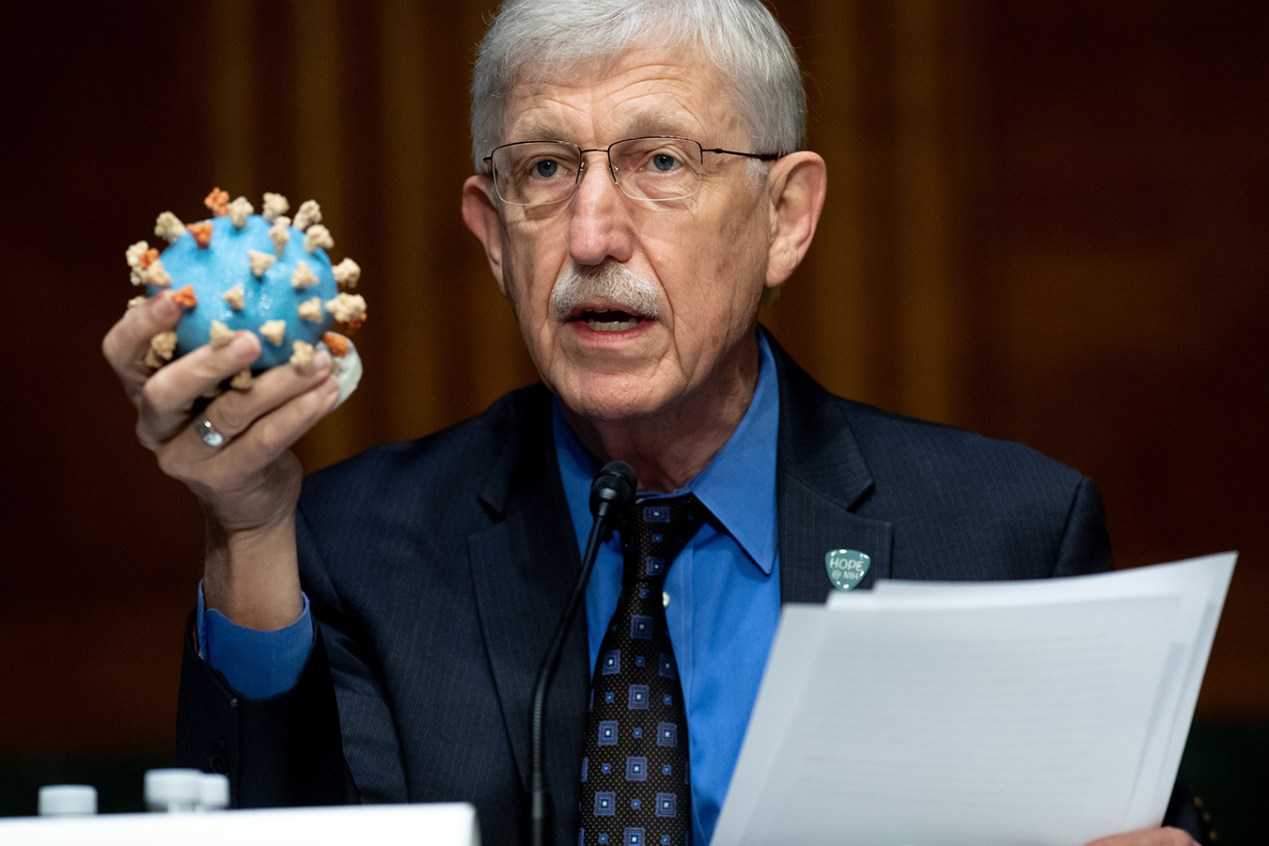

That is in no small part due to NIH’s soft-spoken but politically astute director, Dr. Francis Collins. The motorcycle-riding, guitar-playing Collins announced Tuesday he will step down by the end of the year from his job as chief of the research agency, having served more than a dozen years under three presidents.

“No single person should serve in the position too long,” said Collins in a statement, and “it’s time to bring in a new scientist to lead the NIH into the future.” Collins, 71, said he plans to return to his lab at the National Human Genome Research Institute, which he led for 15 years, from 1993 to 2008. Under his leadership, the institute successfully mapped the human genome, and Collins helped shepherd through Congress legislation to protect the privacy of individuals’ genetic information.

The big question now is not just who will fill Collins’ big shoes at NIH, but whether the agency can maintain its status as a political favorite among members of both parties. Under Collins’ stewardship, NIH’s budget has increased by more than a third during a time of mostly flat federal health budgets, and political interference with biomedical research has been, if not nonexistent, at least mostly off the front pages. That’s in sharp contrast to the CDC, whose handling of the pandemic has drawn plenty of criticism under both Presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden, and the FDA, which tallied its own covid missteps and remains without a nominated commissioner nearly 10 months into the new administration.

While Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the NIH’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has maintained a much higher profile than Collins and also courted controversy, most of that flak did not redound to NIH as a whole.

President Joe Biden praised Collins, calling him “one of the most important scientists of our time.” Noting Collins’ work on the human genome and his help launching the Obama administration’s work on precision medicine, the Brain Initiative and the National Cancer Moonshot effort, Biden said, “Millions of people will never know Dr. Collins saved their lives.”

Accolades for Collins flowed in from the scientific community as soon as news of his impending departure was announced. “For more than a decade Dr. Collins has provided exemplary leadership and stewardship as head of the NIH,” said the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network.

And the praise from politicians was distinctly bipartisan. Sen. Richard Burr (R-N.C.) said in a statement that Collins “led the NIH capably and admirably, leaving it better prepared to meet the challenges of the 21st century.” House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer was no less effusive, calling Collins “one of our country’s greatest public servants, having spent his career working to improve the health of all Americans and promoting cutting-edge research that extends our understanding of the human body and how to heal it.”

It is notable that the relative lack of controversy during Collins’ tenure has been the exception, not the rule, for NIH over the past half-century. Starting in the 1970s, every biomedical advance, from in vitro fertilization to fetal tissue and stem cell research to the cloning of Dolly the sheep resulted in intense political fights and blaring headlines.

In the late 1990s, Republicans led by then-House Speaker Newt Gingrich decided to make science funding a priority and spearheaded a doubling of NIH’s budget, an effort Democrats happily joined. But after that doubling, a stagnant NIH budget caused cutbacks in university research, creating controversy of its own, which Collins had to manage.

Controversy comes with the territory. “Anytime there’s controversy in science, NIH is going to be involved,” said Mary Woolley, president and CEO of Research!America, a science funding advocacy group.

What has set Collins apart, said Woolley, is his ability to communicate to transcend that controversy, “both in ways unexpected, like singing and riding motorcycles, and more traditional ways,” like dealing with lawmakers.

Dr. Ross McKinney, chief scientific officer for the Association of American Medical Colleges, agreed. “He’s just done a dynamite job at being effective at communicating with both sides,” he said. “He’s good with scientists, he’s personally Christian and religious, so he can speak to that side, as well.”

Both Woolley and McKinney said they are confident there are plenty of good candidates to lead NIH, although neither would name any. But McKinney said he hopes the NIH doesn’t end up with a void at the top like the FDA. “I think the FDA precedent is concerning,” he said.

Still, Woolley said, Collins is leaving the NIH in good shape. “The next leader will benefit from what he has done,” she said.

HealthBent, a regular feature of KFF Health News, offers insight into and analysis of policies and politics from KFF Health News chief Washington correspondent Julie Rovner, who has covered health care for more than 30 years.