John Weiser, a doctor and researcher, has treated people with HIV since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s. He joined the CDC’s HIV prevention team in 2011 to help lead its Medical Monitoring Project, the only in-depth survey of HIV across the United States. The project has shaped the country’s response to the epidemic over two decades, but the Trump administration censored last year’s findings and stopped funding it.

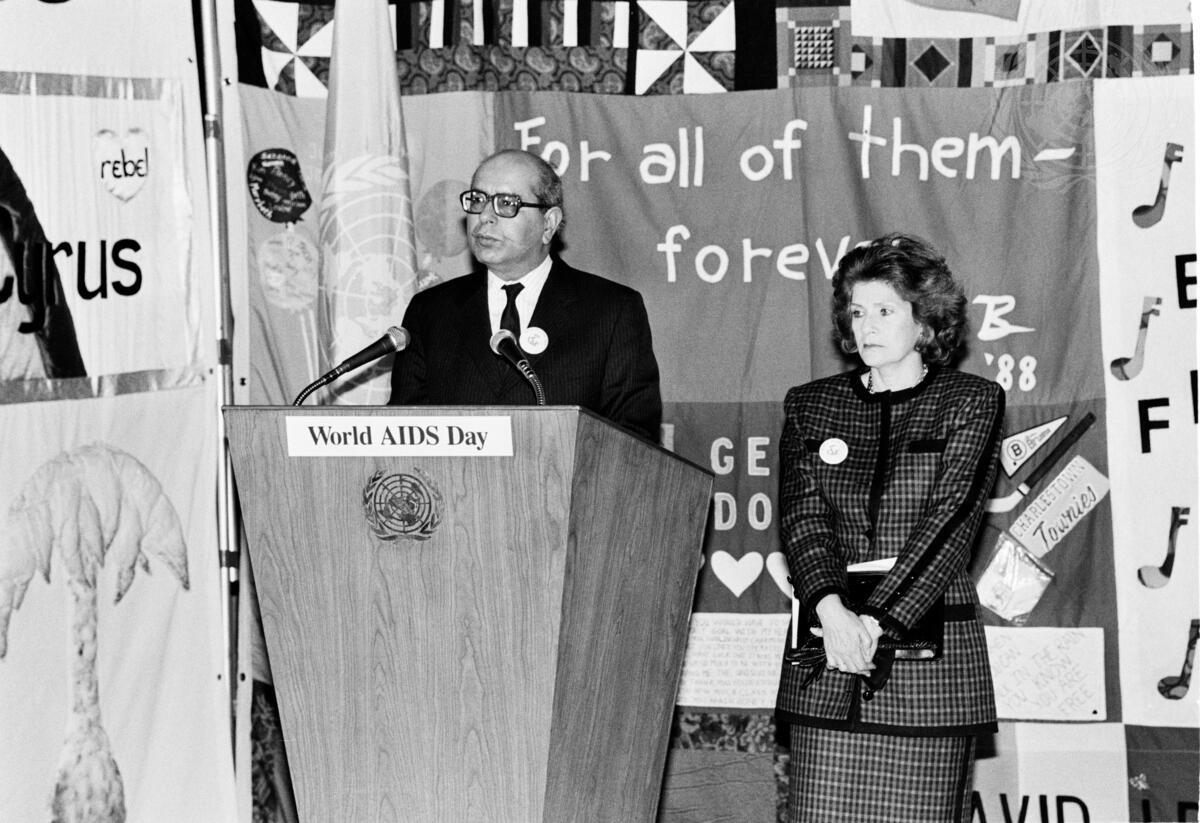

Weiser spoke with KFF Health News on the evening before World AIDS Day, which the U.S. government, for the first time since 1988, didn’t acknowledge this year. That was only the latest blow to efforts to combat HIV. The Trump administration has cut funds to provide lifesaving HIV care abroad, withheld money to prevent and treat HIV in the U.S., and fired HIV experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Weiser was fired from the CDC during mass layoffs in April, was rehired in June, and then resigned. He continues to treat patients at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta. In November, he published an article that warns against complying with presidential orders to censor data about transgender people.

The following conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

LISTEN: Former CDC official John Weiser speaks with KFF Health News correspondent Amy Maxmen about his resignation from the agency and why he thinks complying with President Donald Trump’s orders to erase transgender people is bad for science and society.

In the first weeks of his presidency, Donald Trump issued several executive orders with implications for HIV programs. One directed federal employees to exclude gender identities that didn’t correspond to a person’s biological sex assigned at birth.

On how this played out at the CDC:

We were told to scrub any mention of gender or transgender people from dozens of research papers and surveillance reports that had already been published or were going to be published, and to stop collecting information from participants about their gender identity. For example, we had to recalculate our numbers on HIV among men who have sex with men, or MSM, a category that the CDC changed to “males who have sex with males.”

The CDC had no director at the time. The order came from on high. And there was no discussion about whether we wanted to comply with the directive.

On how this directive has affected his research:

Using data from the Medical Monitoring Project, we found that people with HIV who misused opioids were more likely to engage in behaviors that could pass on HIV to another person — through unprotected sex or shared injection. And we found that very few people who misused opioids were receiving treatments for substance misuse. This information could have been useful to change clinical practice and boost funding to treat people with HIV who misuse opioids.

We were getting ready to publish this study, but when I put the paper through CDC’s clearance process, I was told to remove data about the prevalence of opioid misuse among transgender people.

I thought carefully about that, and I decided not to do that, because it’s bad science to suppress data for ideologic reasons and because erasing people from the story harms actual people. I thought about my transgender patients and how I would face them, and what I would say to them while I’m sitting with them in the exam room, knowing that I had erased their existence from CDC.

I withdrew the paper. It remains unpublished.

On how removing data harms people:

Purging data about transgender people has the effect of erasing them from the real world, pretending that they don’t exist. This group of people is heavily affected by HIV, and this type of information informs improvements in treatment. My transgender patients struggle with poverty, with unstable housing, with food insecurity, with mental health disorders, with substance misuse, and face a huge amount of stigma and discrimination in their daily lives.

My transgender patients are trying to get by, day by day. They’re trying to survive. I think it’s important to realize that somebody who is transgender needs to feel comfortable in their own body to be healthy — and denying them recognition compounds their challenges.

After the executive order came down, one of my patients said she felt even more afraid of being in public and not passing, and so she was considering having additional surgical treatment to feel safer. Her concern was not about politics. It was about survival.

On why the CDC went along with orders to remove transgender data:

I think the hope was that by complying with the directive, other work at the CDC would be spared. And unfortunately, that hasn’t proved to be the case. Funding for the Medical Monitoring Project was terminated after 20 years, and the concern within CDC is that the president will eliminate all HIV prevention and surveillance funding.

One of my concerns while there was that if it’s OK to comply with a directive to remove information about gender, what if the next demand is that we don’t report about people who emigrated from other countries, or on people who are experiencing homelessness? What if there’s a directive to suppress data about a particular racial or ethnic group that’s unpopular? How far would we go?

Some HIV clinics and organizations have considered curtailing their work with transgender people and undocumented immigrants, or on equity initiatives, because they fear the loss of federal funds.

His advice on these decisions:

People making these decisions are in a really tough spot. They want to do what’s best for their programs. They want to do what’s best for their employees. They want to do what’s best for the people they’re charged with taking care of. Those are careful decisions that need to be made weighing all of the considerations. What I want these leaders to do is also consider how a decision to essentially throw one group of people under the bus undermines scientific integrity and harms everyone.

And I think that it’s also necessary for the rise of autocracy to go along, to compromise, to acquiesce. While all of this was going on, I heard an interview with M. Gessen, who is a Russian American journalist who writes about the rise of autocracy. Gessen explained that decisions to go along are not made because people are unethical or heartless. They’re rational choices. They’re made in order to protect something that’s important — institutions, families, jobs — even if it means sacrificing principles. Gessen’s point is that this gradual process of compromising ultimately is what solidifies an autocrat’s power.

On why he resigned from the CDC:

As a physician working at the CDC, numbers have always described individual people, people whose suffering I witness. When you know somebody, they’re no longer just a concept that you make a judgment about.

I realized that I could do more good by spending more time with my patients than I could working for the CDC under this administration.