For Emily Boller, it was a $5,000 hospital bill for a simple case of pink eye that took four years to pay off. For Mary Curley, it was the threatening collection letters from a lab that arrived more than 2½ years later, just as her husband lost his job and the family was fighting to save their home.

For Cory Day, it was a $1,000 fee he was charged at an emergency room outside Los Angeles, even though he only checked in and then left before being seen. “I feel like the hospital is a predator,” Day said. “This is a place that’s supposed to be looking after you.”

The experience offered a stark lesson, he said: “Don’t trust the system.”

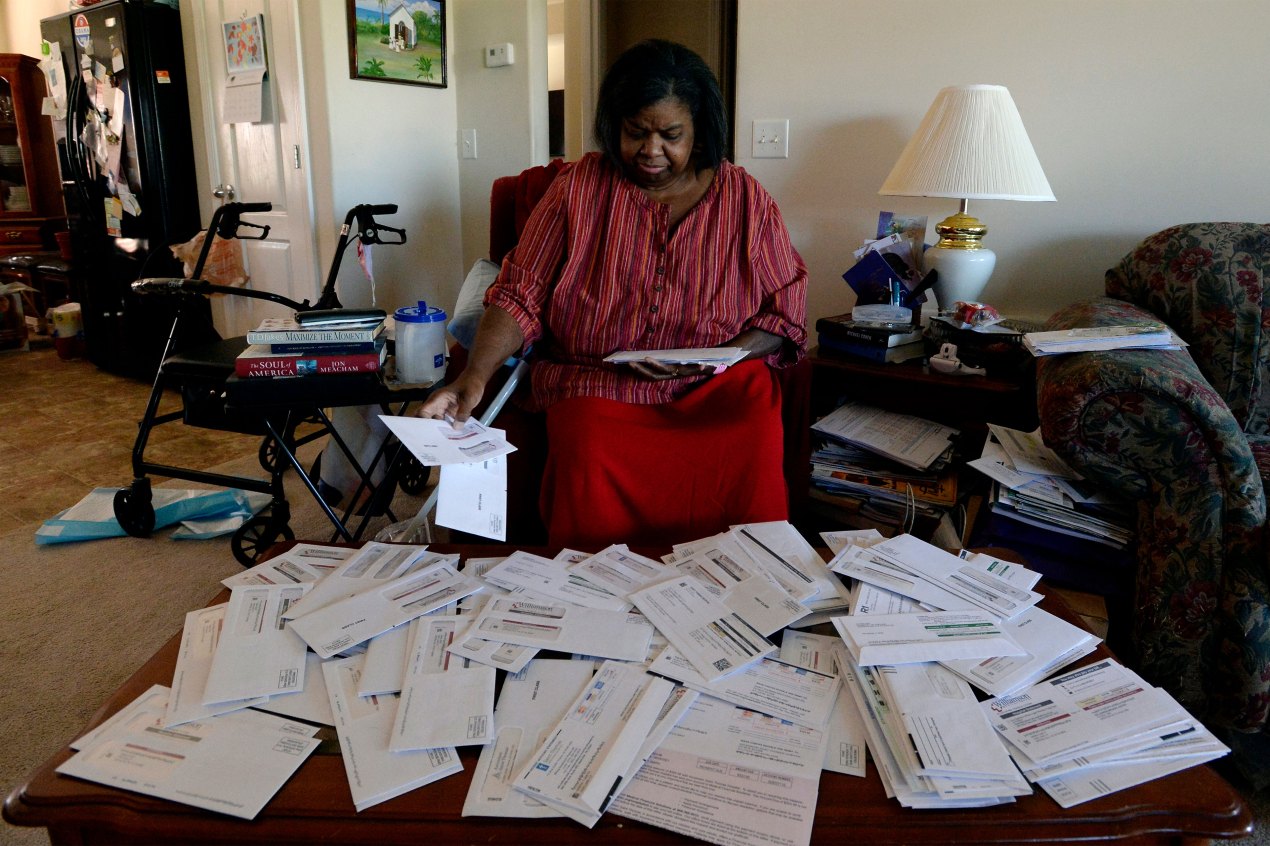

Reporting on medical debt over the past two years, I’ve spent hundreds of hours on the telephone, in the living rooms, and at the kitchen tables of patients like Day, Curley, and Boller. They are among the 100 million people in America whom we found have been driven into debt by medical and dental bills.

Some of my conversations with patients have been heartbreaking. Some enraging. Many have revealed a deep and disturbing disillusionment with our health care system.

Medical providers ignore this at their peril — and at a high risk to Americans’ health.

Doctors and hospitals have long held an exalted position in American life, retaining public confidence even as Americans have steadily lost trust in other institutions such as government, law enforcement, and the media. Growing up, I shared this faith. My father was a physician who never hesitated to get up in the middle of the night and drive to the hospital to operate on a sick child in his care.

But as a journalist covering health care in America over the past 15 years, I’ve seen patients’ faith shaken. They’re tired of shocking medical bills they didn’t expect and can’t afford. And they’re disgusted by the collection notices, the threatening phone calls, and the appointments they can’t get because they owe money.

Many Americans say they simply no longer trust their medical providers. This is borne out by polling we did with our colleagues at KFF as part of our investigation of medical debt. Just 15% of people with health care debt said they have a lot of trust that providers have patients’ best interests in mind. That’s about half the rate among people without such debt.

Many caring people who work in health care understand this. I’ve met countless compassionate physicians, nurses, and others who see firsthand the toll that debt is taking on their patients.

But I’ve seen a lot more denial and finger-pointing by health care leaders. Hospitals and doctors blame the government for underpaying them and blame insurers for selling plans with unaffordable deductibles. Insurers blame providers for obscene prices. Everyone blames drug companies.

The upshot is that each of these medical industries hunkers down and, pleading its own suffering, looks out for its own interests. They rarely talk seriously about what they could do to relieve the financial burdens they create that drive tens of millions of Americans into debt.

And so, the suffering of patients deepens.

In our project on medical debt with NPR, we documented cancer patients forced to hold off debt collectors while fighting off nausea and other toxic side effects of chemotherapy; older workers whose retirement savings were obliterated; 30-somethings unable to buy a home because their credit was ruined by health care debt; new mothers forced to take on extra work; parents unable to buy Christmas gifts for their children; and seniors who cut back on food because of medical debt.

That our health care system would do this to people might be reason enough for hospital executives, insurance CEOs, and senior physicians to stop the blame game and look in the mirror.

If nothing else, this should be a flashing red light: the simmering resentment of growing numbers of patients who feel victimized by this system.

We got a hint of the dangers of this during the pandemic, as Americans who distrusted the medical system proved easy prey for misinformation about vaccines and other public health measures, with sometimes fatal consequences.

Other systemic risks are lurking. I was once a political reporter. I covered mayors and state legislatures and, ultimately, Congress. I saw up close what an erosion of trust can do to a system, and how much more difficult it becomes to get things done when the public loses faith in its institutions.

And as the political turmoil of recent years shows, public anger and disillusionment can produce unpredictable, even dangerous results.

Health care leaders — and physician leaders in particular — could alleviate patients’ financial suffering.

Physician groups and hospital systems, many of which are led by doctors, could look more closely at the bills they send patients and the collection tactics they use. Health insurers, whose leadership ranks also often include physicians, could reconsider the high-deductible plans they sell and ask whether they truly protect their customers. And physicians everywhere could speak up about the financial travails of patients in their care.

Absent action, patients’ trust is sure to erode further. And without the trust of the people it serves, this American health care system cannot long endure.