In some ways, the nation’s COVID testing system is like a game of Jenga: When one piece falters, the entire tower collapses.

Take Sacramento County, home to 1.5 million people and California’s capital. Coronavirus cases started surging in late June, and on July 15, 360 residents were diagnosed, marking an ominous single-day record.

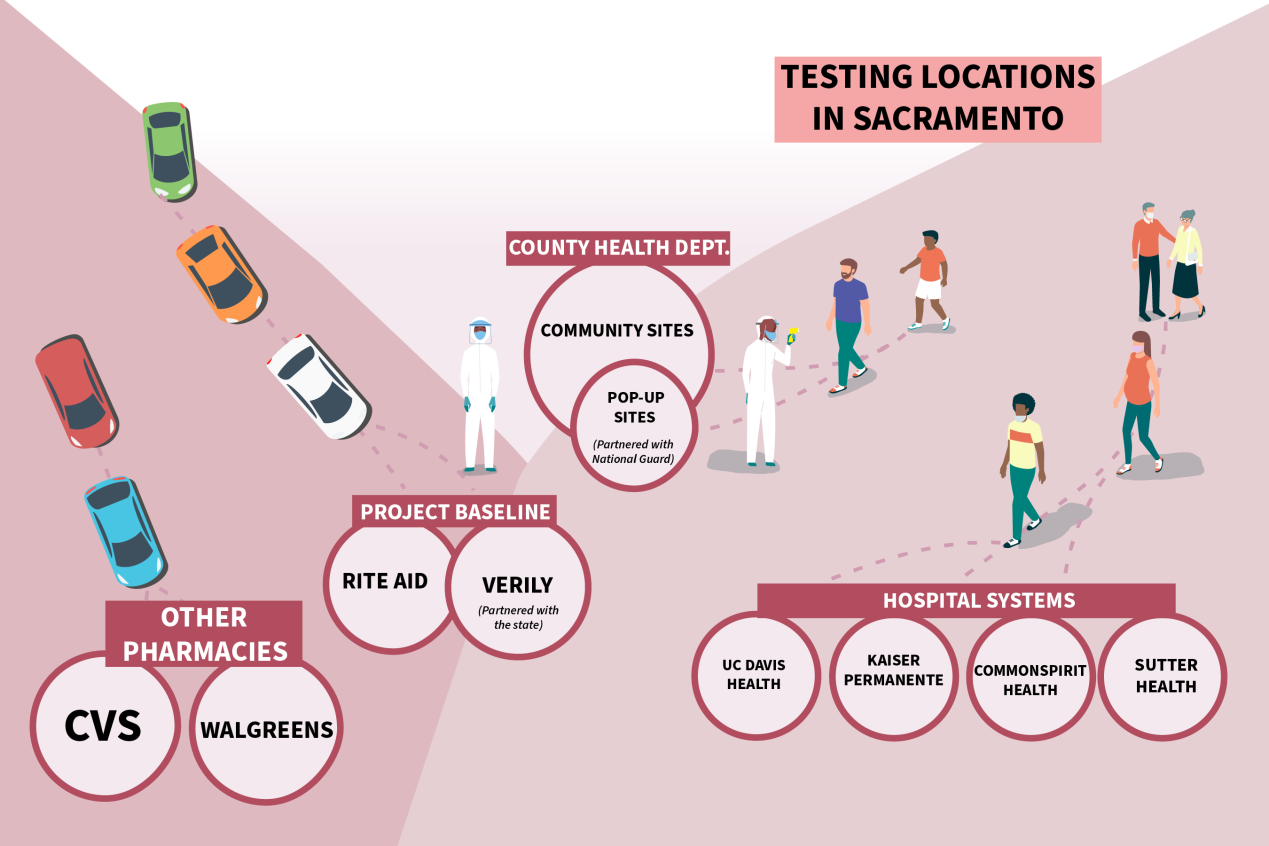

Around that time, people flocked to testing sites run by the state, county, local health systems and other providers, and CVS, the first major retail establishment to start testing in Sacramento County.

But securing a test became next to impossible for many people. Even as Gov. Gavin Newsom touted California’s ability to test roughly 100,000 people per day, Sacramento’s time slots filled quickly, five county-run testing sites temporarily shuttered, and some health care providers limited testing to symptomatic patients.

For those lucky enough to get tested, results took days — sometimes weeks — to return, rendering them essentially useless.

“Results should come in 24 to 48 hours, ideally, from when people are exhibiting symptoms,” said Sacramento County Public Health Officer Dr. Olivia Kasirye. “It impacts our ability to take action and do contact investigations.”

So what happened? Sacramento, like other counties across the state and nation, has been plagued by a series of choke points in its testing system since the pandemic began. During the summer surge, at least two bottlenecks — caused by the sheer volume of tests and a shortage of lab processing supplies — dramatically constricted testing capabilities and slowed results.

“It’s pretty stunning that we are still having these bottlenecks. It was understandable when New York was struggling in March, but why is California struggling now?” said David Lazer, a professor at Northeastern University and co-author of a recent report on turnaround times for test results across the U.S. “It’s a local manifestation of national shortages.”

(Hannah Norman/KHN; Getty Images)

The first choke point emerged in Sacramento as people flocked to testing sites, placing a heavy burden on commercial labs that processed tests, such as Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp.

With COVID hot spots flaring this summer in Sacramento and beyond, the labs faced mounting backlogs, sometimes delaying results by more than a week. During Quest’s second-quarter earnings call in late July, Steve Rusckowski, the company’s chairman, president and CEO, addressed why the lab was struggling to keep up with demand — even as it rapidly increased testing capacity, which is now at 150,000 diagnostic tests a day.

Beyond catering to regions with high numbers of COVID-19 cases, Rusckowski said the lab was also responding to the testing needs of patients scheduled for surgery, high-risk residents at places like nursing homes and prisons, employers testing their workers, and universities requiring tests for returning students.

“There has been … broader availability of testing, where people now have access to asymptomatic testing and very convenient locations,” Rusckowski said. In July, Quest performed 3.5 million diagnostic tests, the company said, compared with 1.5 million in May.

Tests from Sacramento residents were among those, including people who visited the state-funded, drive-thru testing site run by Verily Life Sciences. Pharmacy giant CVS, with its 11 testing locations in the county and more than 1,800 nationwide, also sent its load to Quest, in addition to other commercial labs.

Quest said it has shortened its average turnaround time for tests to two to three days.

Smaller regional operations have popped up to ease the demand. Before the pandemic, Folsom, California-based StemExpress focused primarily on collecting and distributing blood and bone marrow for research and treatments. In early April, the company started processing COVID-19 tests. Now, StemExpress performs tests for Sacramento and other counties, health care systems, private businesses and even the Sacramento Kings NBA team.

About one-third of its business is now diagnostic COVID testing, according to Hether Ide, a company vice president. The lab has the capacity to process 10,000 tests per day, though it generally averages that in a week, Ide said.

To keep up this swift pace, StemExpress early on turned to its supplier, ThermoFisher, for certified COVID testing machines and secured year-long pre-purchasing contracts for the necessary supplies and chemicals. The company hired more than 30 people and staffs round-the-clock shifts to guarantee results in 48 to 72 hours. Still, it’s a fraction of what Quest churns through daily.

“It was a huge front-end financial investment — millions of dollars,” Ide said. “We had to buy the equipment and supply chain.”

Source: KHN reporting and a California COVID-19 Testing Task Force report. (Hannah Norman/KHN; Getty Images)

This brings us to the second major bottleneck: the supplies that big and small labs need to process tests.

In early July, Sacramento had to temporarily close five of its county-funded testing sites because the county’s testing partner, UC Davis Health, could not secure enough reagents — the chemical mixtures necessary to process COVID-19 tests — from Roche, the Swiss manufacturer of its “SUV”-sized lab machine. Major labs nationwide were scrambling for the same reagents.

To get the testing sites back up and running, Sacramento turned to StemExpress — which in April began securing lab supplies intended to last an entire year — to process the tests that UC Davis Health could not. The health system now has adequate supplies and is running about 2,500 tests per week, including some for the county, a UC Davis Health spokesperson said.

Sacramento County has reduced its turnaround time to 72 hours for results, the county said. Sacramento has also recently added community testing sites.

Manufacturers of lab processing supplies have struggled for months to keep up with the global demand. In a recent earnings call, Roche CEO Thomas Schinecker said the company had increased production of PCR testing machines and materials to approximately four times the normal levels. PCR tests, using a polymerase chain reaction, are the most common type used to detect COVID-19.

To avoid relying on one particular manufacturer, many labs use a variety of equipment. For instance, both Quest and BioReference Laboratories operate four FDA authorized testing systems, including ones made by Roche and Hologic, which are the sole makers of their proprietary reagents.

“These labs don’t want to put all their eggs in one basket,” said Marlene Sautter, director of laboratory services at Premier Inc., a group purchasing organization that works with 4,000 U.S. hospitals and health systems.

At the same time, major health systems, including those in Sacramento, face their own supply and testing shortages as they compete for the same equipment.

Kaiser Permanente has ramped up its purchasing of machines, testing kits and chemicals from vendors, and even built a 7,700-square-foot COVID-testing lab in Berkeley, which opened in June. (KHN, which produces California Healthline, is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

Collection Supplies

Earlier in the pandemic, a different supply shortage plagued testing sites in Sacramento: swabs used to collect specimens from people’s nasal cavities for the PCR tests.

In March, Maine-based Puritan Medical Products and Italian company Copan Diagnostics, the two leading manufacturers of these specialized nasal swabs, struggled to keep up with the accelerating demand.

In response, U.S. manufacturers expanded their efforts and Puritan received $75.5 million from the federal government in late April to make more swabs. California’s testing task force, in concert with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said in an early-summer report that it had secured about 14 million swabs. Still, the report says that’s not enough to last through 2020.

Sautter fears that the upcoming flu season will add additional strain on the availability of swabs. Because the flu and COVID-19 share similar symptoms, more people will likely seek testing, and flu tests use the same type of swabs, she noted.

Plus, it’s never clear when one of the Jenga pieces will falter because of manufacturing delays, supply shortages or a spike in testing volume that could jam the system again.

“We really expected a decrease in COVID this summer. Obviously it hasn’t happened,” Sautter said. “Until there’s a vaccine, there’s going to be continued testing demand. Even then, I don’t know if anyone knows when this will be done.”