PEMBROKE PINES, Fla. — A late-morning thunderstorm had just passed when Evaristo Miqueli reached the faded yellow house with its overgrown plants and algae-covered swimming pool and laid a trap to catch Florida’s most wanted mosquitoes.

As Miqueli explored the property, he covered an open pipe, turned empty flower pots upside down and foraged for garbage scraps in plain sight — all to make the place less hospitable for the mosquitoes to thrive. Setting a trap took him less than 10 minutes, and he would return the next day to retrieve his catch.

“We are not just killing mosquitoes, we are disease hunters,” said Miqueli, a biologist for Broward County Mosquito Control, which is based west of Fort Lauderdale.

Miqueli is on the front line in the ground war against this year’s two most-feared urban mosquitoes — Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (also known as the yellow fever mosquito and Asian tiger mosquito, respectively). Both can spread the dangerous Zika virus, which causes devastating birth defects in babies and has been called a global health emergency by the World Health Organization.

The United States has seen more than 700 Zika cases in the past year, all of them related to people traveling from Brazil and countries in Latin America and the Caribbean where they were infected. Florida, the main U.S. gateway to those regions, leads all other states with 185 cases as of June 16. Broward County’s 24 cases is second only to neighboring Miami-Dade’s tally of 55.

Broward is one of about two dozen local governments in Florida that are collectively seeking millions of dollars in federal funds to squash the Zika threat. Congress has been haggling over the size of Zika’s emergency budget since winter. House and Senate negotiators are poised to begin talking about a deal in coming days.

Their battle plan is simple but effective: Hire more inspectors. Buy more insecticide. Lay more mosquito traps. The generals leading Florida’s mosquito control forces want to be ready for the first locally acquired case, which will trigger a ramp-up in surveillance and spraying.

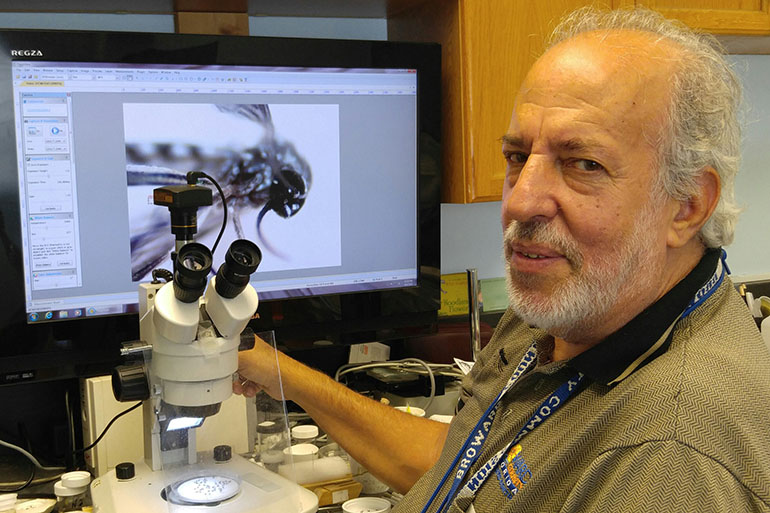

Mosquito-fighting pros such as Miqueli, 67, who keeps a clear garbage bag with thousands of the dead insects in his office, are an often forgotten part of the nation’s public health system both in Florida and nationally — until an outbreak occurs.

At the Broward County Mosquito Control office in Pembroke Pines, Florida, biologist Evaristo Miqueli holds a bag of thousands of dead mosquitoes his agency has caught in 2016. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

Year in and year out, mosquito control is a steady march of tracking, spraying and surveillance that, in the absence of a vaccine, provides the best defense against disease. Nationally, such duties are carried out by mosquito-control agencies run by cities and counties or specially funded local taxing districts. Some of the foot soldiers work for local health departments, and others are assigned to departments of agriculture, transportation, or parks and recreation. In Broward, mosquito control is part of the county public works department.

“The way Florida handles mosquito control varies greatly,” said Michael Farzan, vice chairman of the department of immunology and microbial science at Scripps Research Institute in Jupiter.

No place spends more per capita in Florida than Lee County, an area of 700,000 residents including Fort Myers on the state’s southwestern coast. Its special mosquito control district — funded by local property taxes — has an annual budget of $24 million, which pays for 86 employees, 10 helicopters and four propeller planes for spraying.

In contrast, Miami-Dade, Florida’s biggest county with 2.6 million people, spends $1.6 million a year and has 15 employees. Broward County, with a population of 1.9 million, has a $1.3 million budget and a mosquito control staff of 15.

Miami-Dade’s relatively low mosquito-fighting budget and its role as a transportation hub for visitors from South and Central America, where Zika is rampant, could make the county vulnerable to a Zika outbreak, said Farzan. Yet, Miami-Dade officials talk down such fears.

Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, one of the species that can spread Zika, lay in a petri dish at the Broward County Mosquito Control. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

“We are confident that Miami-Dade County is prepared to fight the mosquito species capable of transmitting the Zika virus,” said county spokeswoman Gayle Love. The county has a long history of controlling mosquito borne illness, she noted. “In the past, our community has faced West Nile virus, dengue fever and chikungunya, with only a handful of locally transmitted cases.”

West Nile can cause serious neurologic illnesses in less than 1 percent of cases, but most people infected develop no symptoms. Dengue results in flu-like symptoms for most people, but the less-common dengue hemorrhagic fever can be fatal if not recognized and left untreated. Chikungunya most often leads to severe joint pain.

Florida mosquito control agencies statewide have visited the homes of hundreds of people suspected of having Zika, based on alerts from their doctors to health departments. The agencies spring into action without waiting for confirmation from blood tests, which may take a week or more to get results.

Because the mosquitoes that may spread Zika only travel about a hundred yards, inspectors mainly spray in the immediate area around a Zika-infected human’s home and try to remove standing water. That offensive is aimed at preventing Zika-carrying mosquito species from biting people already infected with the virus, spreading Zika into the general mosquito population and infecting more people.

Even though they are looking for federal funding, Florida mosquito-control forces say they aren’t panicked about carrying out their mission.

“The Florida mosquito control districts are fully prepared to handle Zika as this is not our first rodeo with these two mosquitoes,” said Terry Torrens, referring to Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, which spread dengue and chickungunya in Florida. Torrens is mosquito control director for Osceola County, south of Orlando.

“We have been hunting and killing these species effectively for years. Florida is slap full of decorated and published mosquito professionals housed in districts across the state, we are ready.”

Mosquito hunters like Miqueli are laying traps to both count the number of the specific mosquito species that carry Zika and also bring in mosquitoes for testing to find out if they are carrying the virus. The state has tested nearly 5,000 mosquitoes since May and all were negative for the virus.

Steve Noe, project manager of Martin County Mosquito Control in Florida, examines water from a bucket at a home he visited. Noe can see the larvae for one of the mosquito species that can spread Zika, Aedes aegypti, swimming in the bucket. (Phil Galewitz/KHN)

Meanwhile, the mosquito control districts across Florida report a surge in calls from worried homeowners and businesses seeking protection. Even before the heavy rains began in the past month, Broward County was getting close to 400 calls a day for mosquito spraying, twice the normal amount for spring.

“We are meeting the demand, but my biggest concern is what happens if we get a localized outbreak and we need additional resources,” said Anh Ton, who oversees the Broward operation.

If his worry comes to pass, county inspectors will have to widen their surveillance radius to at least a mile around the home of an infected resident, he said. Broward has asked for $650,000 in additional federal money to bring on four more inspectors to help the eight it employs plus four more trucks for spraying.

Finding Zika-carrying mosquitoes is crucial because that will guide the Florida’s summer assault to the right spots, Miqueli said. The traps that Miqueli and others lay down attract mosquitoes with chemical scents that simulate a human’s and they contain dry ice to keep the insects alive long enough to be taken to a state lab for testing.

In the mosquito hunters’ view, experience and confidence counts for a lot.

Martin County’s mosquito control section, about 100 miles north of Miami, beat back a dengue outbreak in 2013. Steve Noe, its project manager, knows his enemy so well he can point out the Aedes aegypti mosquito larvae without a microscope by the way it swims through water in a bucket.

Noe has no doubt his team has what it takes to handle the latest threat. “It’s all about having boots on the ground,” he said. “We crushed it before.”