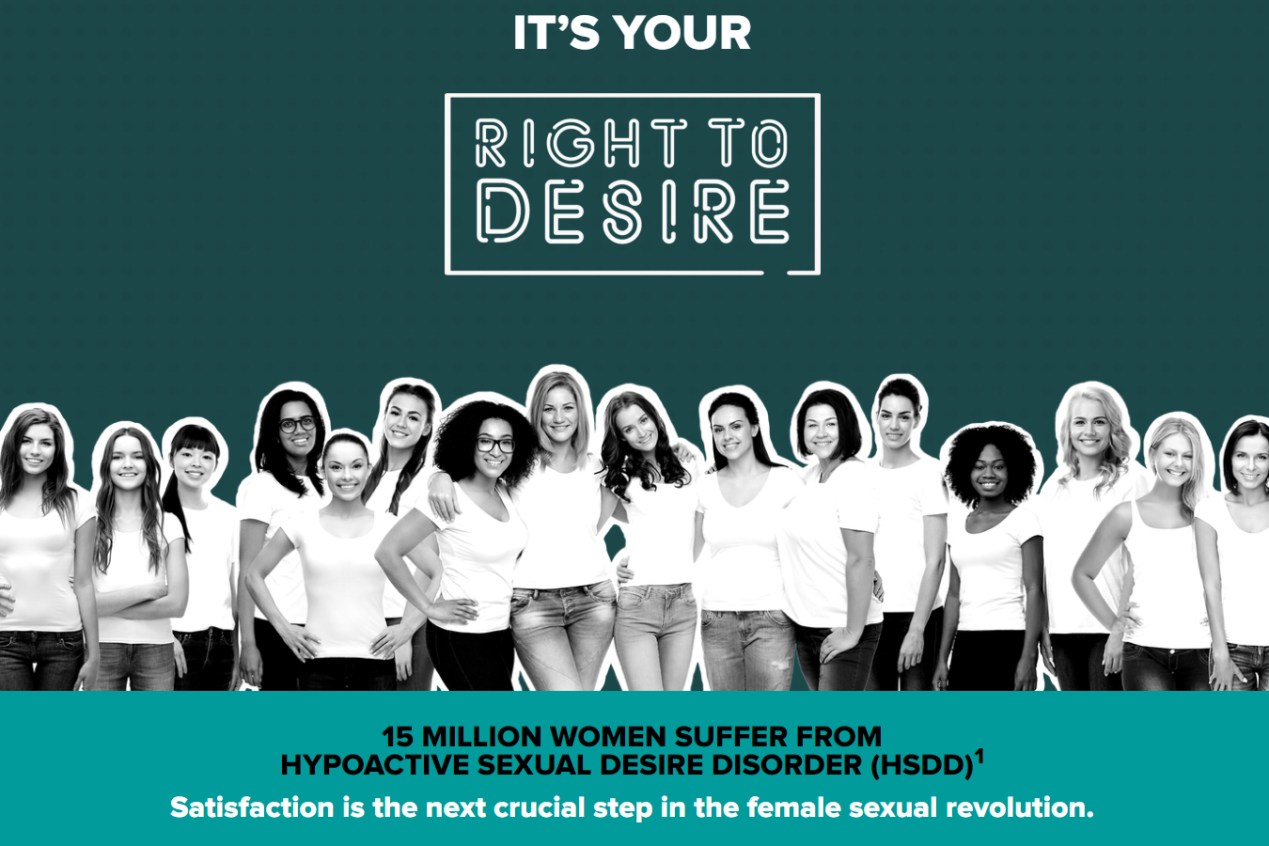

Studies have never defined a “normal” level of sexual desire. Despite that, there’s a website and an online quiz to help you decide if you’ve got a problem. Called “Right to Desire,” it brands libido as a feminist “right,” and its home page offers the defiant, in-your-face prompt: “Yes, I want my desire back.”

Click a few boxes and you’re instantly directed to a remedy (and an online doctor to prescribe it): a pill called Addyi from Sprout Pharmaceuticals.

“This particular product should not have been approved by FDA, but it was, and it is not a product that adds value to women’s lives,” said Susan Wood, assistant commissioner for women’s health at the Food and Drug Administration from 2000 to 2005.

She added: “There isn’t an actual market.”

The effort, called a “disease awareness” campaign, troubles critics because it attempts to define low sexual desire as a widespread disease that is treatable with a pill. Although doctors recognize that there is (perhaps) a condition called Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder, many of the studies defining HSDD were sponsored by the drugmaker. Almost all doctors on the 2016 consensus panel that defined HSDD were consultants or on Sprout’s advisory board.

To further complicate matters, in the studies that led to Addyi’s approval, results were not terribly impressive. And, for those who would simply like a little more sex in their lives, is it worth a $400-a-month pill?

Enter the latest sales pitch, which encourages women to stand up for their rights. The new campaign taps into emotional issues that have long been staples of women’s equality movements, like the right to equal access to health care, the idea that women’s issues should be taken as seriously as men’s, including women in conversations about their health and valuing women as sexual beings.

“To hear our language co-opted” is upsetting, Cindy Pearson, the executive director of the National Women’s Health Network, said in an interview. “It’s really bittersweet to see it co-opted to sell, and sell a product that isn’t that good.”

Addyi — also known as flibanserin — first gained FDA approval in 2015 after a long and contentious fight. It’s often called the “female Viagra” because it’s related to sex, but Addyi and erectile dysfunction meds are quite different.

While impotence medications work by directing blood to the genitals and are taken before sex, Addyi is taken nightly and works in the brain to increase desire.

In fact, it was originally developed to be an antidepressant, but its clinical-trial performance fell short. Along the way, researchers noticed that subjects reported having some increase in sexual desire.

“Addyi is believed to work on the part of the brain involved in sexual motivation and response, though its exact mechanism of action is not fully understood,” the official website reads.

Even during drug trials, Addyi’s effectiveness was questioned. On average, women who took it reported one increased sexually gratifying experience every other month, and that was only after the subjects began recording their experiences monthly instead of daily.

There are also concerns about side effects like dangerously low blood pressure, fainting, severe drowsiness and insomnia.

The FDA rejected Addyi twice before it went before a public advisory council, where patients, doctors and women’s groups (some funded by the manufacturer, according to industry researchers) testified in favor of the drug.

In the old days, drugmakers developed drugs for known diseases. Now drugs come looking for a market.

It’s difficult to pinpoint the number of women who report a persistent lack of sexual desire. Even the findings of studies sponsored by the drugmaker vary widely. Such complaints also tend to be more common among post-menopausal women — a group for whom the drug is not approved.

Experts say it’s difficult to get an accurate picture of the problem medically known as low libido because it has so many possible causes — depression, poor body image, fatigue, stress, pregnancy and menopause. Even in the Sprout-sponsored study, many women who were distressed about their low sexual desire ascribed it to “relationship issues.”

“You take something that can occur from a wide range of reasons, some of which have nothing to do with physiological or medical problems, and you turn it into a medical problem, you give it a name and you sell a product to get rid of it,” said Diana Zuckerman, the president of the National Center for Health Research.

Rather than turn to a costly, silver-bullet medication approach, complaints like sexual dysfunction and low desire often need to be addressed by mental health professionals, sexual health professionals or people with more time and training than general practitioners, Zuckerman said.

Anyway, Addyi’s labeling expressly notes it is not approved for use by women whose low libido is caused by problems in their relationship, menopause, childbirth, medical issues, other medications they are taking or mental illness.

While Wood said she thought Sprout would like to market Addyi to “almost all women,” there’s a “tiny subset of women who suffer from HSDD.”

“And there’s not a big a market of people who actually suffer from this diagnosable condition that could benefit from a medical treatment,” Wood added.

Addyi’s labeling expressly notes it is not approved for use by women whose low libido is caused by problems in their relationship, menopause, childbirth, medical issues, other medications they are taking or mental illness.(Screenshot from addyi.com)

“Right to Desire” brands itself as a movement for women who are struggling with HSDD. The campaign is heavy on social media, with a strong Facebook presence that includes Funny or Die videos, date night “hacks” and testimonials from patients and doctors. There was a #RightToDesire “girls’ night out” Twitter party featuring several mommy bloggers and giveaways.

It’s not the first time feminism has been used to sell a product, but it’s still frustrating for women’s health activists who have been working for years to get their issues taken seriously.

At the time, a coalition of groups — some venerated women’s rights groups and some that were formed and funded by the pharmaceutical industry — known as “Even the Score” pushed for the drug’s approval and found traction. The rallying cry was the idea that 26 drugs had been approved for male sexual dysfunction and none for women.

“I believe [the FDA] found it hard to keep the product off the market when they were being accused of being sexist,” Wood said.

“They got, in my view, sort of bamboozled by that argument,” she added.

Forty-eight hours after Addyi was approved, Sprout sold it to Valeant, now under the umbrella of Bausch Health Companies, for around $1 billion.

And it flopped. According to Wood, that’s because the drug didn’t work, came with safety concerns and wasn’t covered by many insurance plans. Addyi cost around $800 a month for a daily pill, which may account for why at its peak in March 2016 only 1,600 prescriptions were written for it.

In 2017, Valeant gave up on Addyi, turning it back over to Sprout, which is now trying again to make the drug a sensation. As part of the arrangement, according to press reports, Sprout did not have to pay an upfront fee and, among other parts of the deal, agreed to pay Valeant, now Bausch, royalties on sales of the drug, though early indications say it still isn’t successful.

“We will receive royalties once they make a milestone,” Arthur Shannon, senior vice president and head of investor relations and communications for Bausch, wrote in an email. “We have not received any royalties thus far.”

The deal paved the way for a lower price tag — cut in half — and this trendy pop-feminist ad campaign.

Sprout did not make its CEO available for an interview.

Originally, the drug’s labeling included a prohibition on drinking alcohol while on the medication. This caution, though, resulted from a study whose participants were mostly men.

This spring, Sprout funded two new studies to show Addyi was safe to consume with alcohol, but the FDA kept the “black box” warning in place with one change — the alcohol prohibition is restricted to two hours before and at least eight hours after taking it.

“Now is the time to lend your voice and demand gender equality when it comes to sexual health,” the Facebook page declares as it directs visitors to a Change.org petition to get benefits managers to cover the drug. It also asserts that it’s “time to address women’s sexual health beyond reproduction alone.” It even quotes Eleanor Roosevelt.

“[Sprout is] definitely appropriating all that language, making it seem like a feminist issue,” said Dr. Steven Woloshin, a professor at the Dartmouth Institute. “This is an issue that involves women, but that doesn’t mean that taking this drug is something you should do because you’re a feminist.”