[UPDATED at 2 p.m. ET on March 26]

The chairman of the Senate health committee on Tuesday backed new federal regulations to remove roadblocks patients can face in obtaining copies of their electronic medical records.

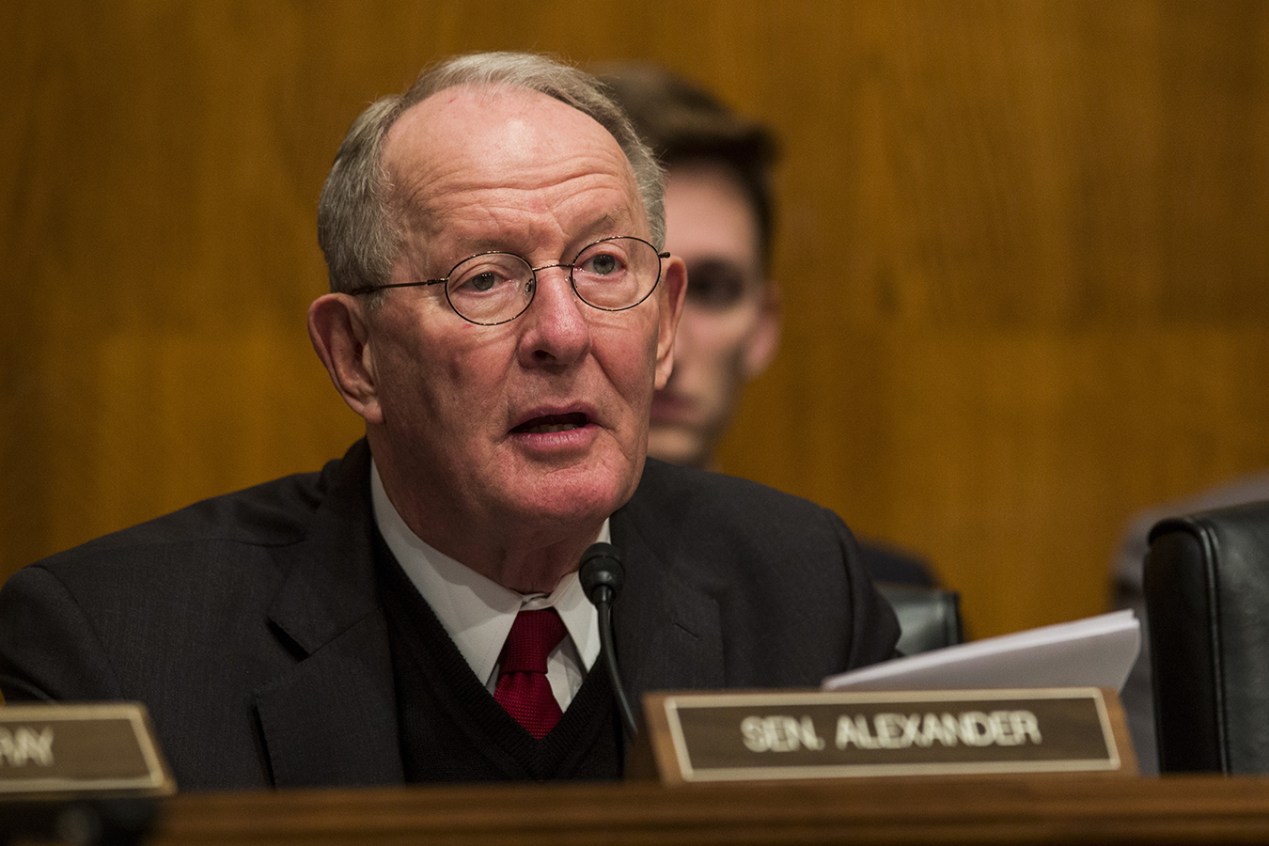

“These proposed rules remove barriers and should make it easier for patients to more quickly access, use and understand their personal medical information,” Lamar Alexander (R-Tenn.), chairman of the Health, Education, Labor & Pensions Committee, said in a statement prepared for a hearing on the rules that kicked off Tuesday at 10 a.m.

The rules, proposed last month by the Department of Health and Human Services, take aim at so-called information blocking, in which tech companies or health systems limit the sharing or transfer of information from medical files.

Alexander said HHS believes the new rules should give more than 125 million patients easier access to their own records in an electronic format.

“This will be a huge relief to any of us who have spent hours tracking down paper copies of our records and carting them back and forth to different doctors’ offices. The rules will reduce the administrative burden on doctors so they can spend more time with patients,” Alexander said.

The proposal requires manufacturers to fashion software that can readily export a patient’s entire medical record — and mandates that health care systems provide these records electronically at no cost to the patient.

Congress jump-started the nation’s switch from paper to electronic health records in 2009 using billions of dollars in financial stimulus funding to help doctors and hospital purchase the equipment. Officials expected the shift to cut down on medical errors, reduce unnecessary medical testing and other waste and give Americans a bigger role in managing their health care.

Yet in the decade since the rollout, critics have argued that the government spent billions financing software that can cause some new types of errors and typically cannot share information across health networks as intended.

“Botched Operation,” a recent investigation published by KHN and Fortune, found that the federal government has spent more than $36 billion on the initiative. During that time, thousands of reports of deaths, injuries and near misses linked to digital systems have piled up in databases — while many patients have reported difficulties getting copies of their complete electronic files.

Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), ranking member on the committee, cited two patients profiled in the article to illustrate the potential dangers from EHRs that can’t exchange information.

“It’s patients who get hurt. Like the man in California, who suffered brain damage after his diagnosis was delayed because a hospital’s software couldn’t properly interface with a lab’s software,” she said at the hearing. “Or the woman in Vermont, who died of a brain aneurysm that might have been caught if a software problem hadn’t stopped the order for a test she needed.”

Jonathan Lomurro, a medical malpractice attorney in New Jersey, said his clients usually have to go to court to get their complete medical record. The information that health care providers fight most bitterly to keep from them, he said, are the audit logs — or the data that show every time a record has been accessed or edited, and by whom and when.

That “metadata,” he and other plaintiff attorneys argue, is critical for patients to understand the history of their care, particularly in cases where something has gone wrong.

In an interview prior to Tuesday’s hearing, Lomurro criticized the HHS proposal, saying it limits a patient’s ability to obtain these logs. While the proposed rule requires the systems to share most data from a medical record with a patient, it excludes audit trails from that classification.

“While the proposal talks about the need of patient access … they then strip the greatest protections from the patient,” said Lomurro. “I am at a loss on how this could ever be a beneficial change to the rules and help patients.”

Seema Verma, who heads the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, agreed that patients should be entitled to audit log information. “At the end of the day, it’s all of the patient’s data. If it affects and touches their medical record, then that belongs to them,” Verma said in an interview last month.

The HHS proposal also encourages doctors and other users of EHR technology to share information about software problems they encounter by prohibiting “gag clauses” in sales contracts. Critics have long argued that the clauses have prevented users from freely discussing flaws, including software glitches and other breakdowns that could result in medical errors and patient injuries. In 2012, an Institute of Medicine report blamed the confidentiality clauses for impeding efforts to improve the safety of health information technology.

But a major remaining problem in wiring up medicine is the lack of interoperability across rival data systems, said Christopher Rehm, chief medical informatics officer of LifePoint Health, a hospital system in Brentwood, Tenn. In testimony prepared for the Tuesday hearing, Rehm called it “the equivalent of telling people they must buy cars and move those cars from place to place, but there are no roads and no agreed-upon design for the roads, let alone the funding to actually pay for the construction.”

According to Rehm, the average-sized community hospital (161 beds) spends nearly $760,000 a year on information technology investments needed to meet federal regulations. He said the costs “are crushing our industry where margins are already thin.”