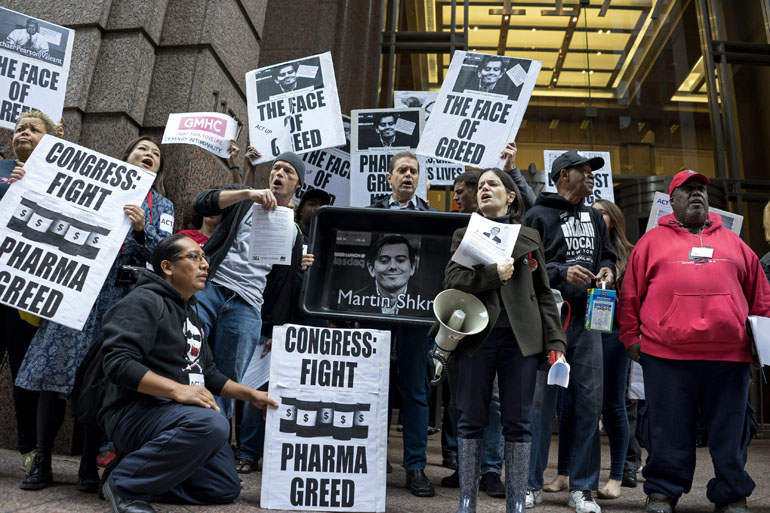

When Turing Pharmaceuticals raised the price of an older generic drug by more than 5,000 percent last month, the move sparked a public outcry. How, critics wondered, could a firm charge $13.50 a pill for a treatment for a parasitic infection one day and $750 the next?

The criticism led Turing’s unapologetic CEO to say he’d pare back the increase – although no new price has yet been named – and the New York attorney general has launched an antitrust investigation. The outcry has again focused attention on how drug prices are set in the United States. Aside from some limited government control in the veterans health care system and Medicaid, prices are generally shaped by what the market will bear.

A jump in the number of new expensive drugs hitting the market — along with moves by drugmakers like Turing to raise the price on older and generic drugs — have helped make prescription drugs the fastest-growing segment of the nation’s health care tab. Prescription drugs account for about 10 percent of all health care spending. Two ideas for curbing that spending surface every time a price spike renews interest in drug costs: Letting consumers buy products from other countries with lower prices set by government controls, and allowing Medicare administrators to negotiate drug prices, from which they are currently barred.

Both proposals are getting an airing in Washington and on the campaign trail, pushed by Democratic presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders. Opposition is heavy, particularly to Medicare negotiations, and neither is likely to gain much traction.

Drugmakers and some economists argue that price controls or other efforts aimed at slowing spending by targeting profits mean cutting money that could go toward developing the next new cure. Because many pharmaceutical companies spend more on marketing than research, some lawmakers counter that the industry could spend less on promoting its products. Health insurers, in turn, blame drugmakers for high prices, even as they shift more cost to consumers, who then fear they won’t be able to afford their medications.

Aside from the perennial ideas, what else is being tried to combat rising prices or at least bring some relief to consumers?

1) Disclose drug development costs

Lawmakers in several states, including New York, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, have introduced “transparency” measures that would force drug companies to provide details on how much they spend researching, making and advertising their products. Proponents say public disclosure would force companies to justify their pricing. Skeptics say disclosure alone may not be enough, so some proposals go further. Massachusetts, for example, would gather price information on a set of drugs deemed critical to the state — and create a commission that could set prices for drugs deemed too costly. None of the measures have passed. On the national front, Clinton proposes to require companies that benefit from federal investment in basic science research to invest a certain amount of their own revenue in research and development.

Some economists say the state and national effort is misguided. Research costs aren’t a good way to justify a drug’s ultimate price, they say. Looking at a single drug produced by a company ignores the huge amounts spent on other products that failed but still provided clues for the product that did succeed. And, some economists say, such rules might simply foster more money spent on research that isn’t needed.

2) Cap consumer copayments

The growing number of insurers placing certain high-cost drugs in categories in which consumers have to pay a percentage of the cost — often upward of 30 percent — has caught the attention of lawmakers in a handful of states, including Montana, California and Delaware. They’ve passed laws capping the amount insured consumers must pay at the pharmacy counter as their share of a drug’s cost. The pocketbook cost for patients is still high, ranging from $100 a month to $250, depending on the state. Still, that’s less than what consumers currently pay for some drugs in many health insurance plans. While such laws could help consumers with out-of-pocket costs, it doesn’t affect the underlying price of those drugs. Critics say in some cases, such rules may encourage greater use of costly drugs for which there are less expensive alternatives.

3) Pay up if the product delivers

A drug’s price should reflect its effectiveness, according to new efforts under way. Benefit manager Express Scripts, for example, next year will pay varying amounts for a small set of oncology drugs based on how well the products perform on different types of cancer. The plan will target drugs that work well on one type of cancer — based on clinical data submitted by drugmakers to the Food and Drug Administration — but are less effective against other types. For instance, the drug Tarceva, when given for non-small cell lung cancer, prolongs life an average of 5.2 months, a big advance for lung cancer treatments, said Steve Miller, senior vice president and chief medical officer at Express Scripts. But, when the $6,200-a-month drug is used to treat pancreatic cancer, it prolongs life an average of only 12 days. Under the new program, insurers would pay the drugmaker less when the treatment is given to pancreatic cancer patients. “We’re trying to slow the rising cost of treating cancer,” said Miller, who said if it works with a small set of cancer drugs, the firm may look to expand to other types of treatments. Variations on the theme are being explored by others, including Novartis, which has said it is in talks with insurers about varying payments based on how well its new heart drug prevents hospitalizations. Both pricing plans face obstacles, such as how to set the right price and how to determine if it was the drug — or something else — that led to fewer hospitalizations.

Meanwhile, consumer groups are cautious, saying such “pay-for-value” ideas hold promise, but only if patients aren’t kept from needed medicines.

These are just three of the proposals being weighed as solutions to combat rising drug prices, but none of them will provide a quick fix.

Price spikes aren’t the only reason the drug industry is under scrutiny. Experts advocate for more education for both doctors and consumers; specifically, they say comparative information about drugs and costs should be more widely available.

Doctors often don’t know how much a particular treatment costs, which is “one of the reasons why [increased] competition isn’t a big enough factor,” said Joseph Antos of the American Enterprise Institute. “I hope this concern about high drug prices would translate into a stronger push for getting beyond platitudes about creating informed consumers and actually doing it.”

Unbiased, medical information about the use of new drugs needs to be easier to get as well, said Jerry Avorn, a professor of medicine at Harvard. That’s particularly true with expensive new products like injectable cholesterol control medications that hit the market this summer. Aside from some patients with a rare form of hereditary high cholesterol, the $14,000-a-year drugs were approved by the FDA only for those patients for whom a less expensive class of drugs, called statins, have been unable to control their “bad” cholesterol levels.

“We’ve got to get word out to doctors, ‘Here’s this new class of drugs and here’s who needs it and here’s who doesn’t,’” Avorn said. He has long supported “academic detailing,” which sends representatives to doctor offices with such detailed information. “It’s important to get to doctors with the best evidence, so they’re not just relying on the [pharmaceutical] sales representative.”