When the first U.S. case of a new coronavirus spreading throughout China was confirmed last week in Washington state, public health workers were well prepared to respond, building on lessons learned during the outbreak of measles that sickened 87 people in the state in 2019.

As of Monday, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had confirmed five cases of infection from the new coronavirus in the U.S., including two in California, one in Illinois and one in Arizona. All were linked to people who traveled to the Wuhan region in China. More than a hundred people are under investigation for the new coronavirus in 26 states, according to the CDC.

The first U.S. patient, an unidentified man in his 30s, had traveled to the Wuhan area at the end of last year. He fell ill shortly after flying back to the U.S., where he lives north of Seattle.

In Washington state, health agencies have identified more than 60 people who came in close contact with the infected man before he was hospitalized in Everett, a city in Snohomish County outside Seattle.

The case quickly grabbed national headlines, but it didn’t rattle the local health clinic workers who had recently geared up to handle another infectious disease.

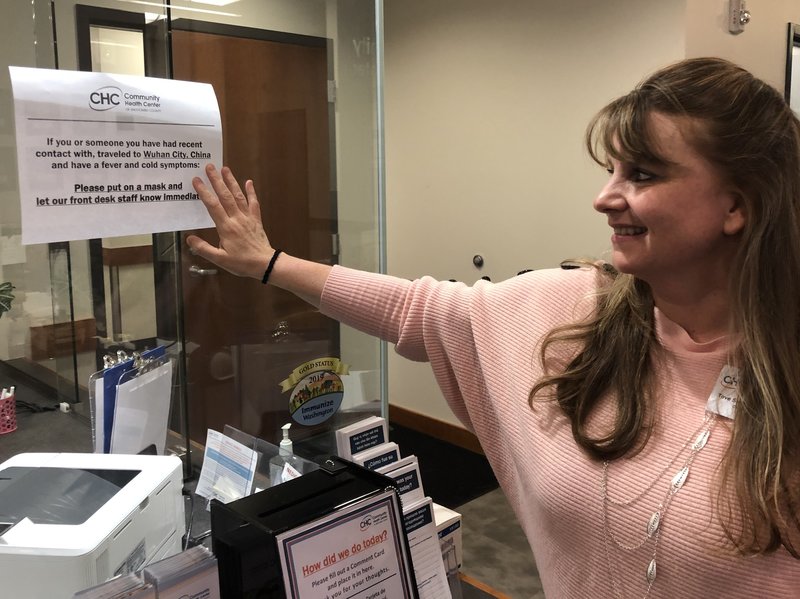

“The measles really kind of enlightened everybody about ‘Wow, there are a lot of things out there that can be really contagious and can get you really sick, really fast,’” said Tové Skaftun, the chief nursing officer for the Community Health Center of Snohomish County.

Skaftun said she’s glad that last year’s outbreak forced them to improve how they approach these situations.

“We’ve recently grown our infection-control program so it’s kind of at the forefront of a lot of what we do,” said Skaftun.

She said that effort focused on educating staff about the correct precautions to take when faced with different kinds of infectious diseases — including wearing protective air-purifying respirators when in contact with patients who may be infected.

Measles is one of the most contagious viruses and can stay in the airspace of a room for up to two hours. In contrast, public health experts believe the new coronavirus requires close contact to spread between humans.

“Coronaviruses are generally transmitted through sneezing, coughing and close contact with individuals, so those are the types of criteria we use to identify people at risk,” said Dr. Kathy Lofy, Washington’s state health officer.

She said previous outbreaks and most recently the measles outbreak led to “a lot of preparation by our health care system partners around how to appropriately … protect themselves from highly infectious pathogens.”

In Washington, public health workers are daily calling people who have come in contact with the confirmed case and asking about symptoms such as a fever or cough. Those being monitored are not required to be isolated unless they develop symptoms.

The patient in Seattle first went to a local health clinic when he started showing symptoms. Once it became clear he was at risk for coronavirus, he was transported to Providence Regional Medical Center in Everett, a hospital north of Seattle, where he was treated in isolation. He remains in “satisfactory” condition, according to the Washington State Department of Health.

Dr. Amy Compton-Phillips, the chief clinical officer at Providence St. Joseph Health, which runs that hospital, said it was set up to handle high-level infectious pathogens during the Ebola scare of 2014.

“All types of infrastructure had been put in place to ensure that when something came around we’d be ready,” said Compton-Phillips.

Those include specialized gurneys to keep patients isolated while they’re wheeled around the hospital, robots that can listen to patients’ lungs and take blood pressure, and rooms with negative-pressure airflow so germs aren’t circulated throughout the rest of the hospital.

In Snohomish County, health workers are on alert for signs that any patients could be at risk of carrying the new virus. At the Community Health Center of Snohomish County, signs posted in the waiting room tell patients to notify staff if there’s any indication they could have been exposed.

“We do have patients that are calling in, and we do have patients that are talking about it with their provider staff,” said head nurse Skaftun.

Skaftun said it’s natural that some patients have been asking questions, but like other health providers in the area, her clinic had all the right protocols and infection-control gear at the ready when they first heard the news.

Last year, Clark County, Washington, which is in suburban Portland, Oregon, had an alarming outbreak of 71 cases of measles, mostly among unvaccinated children. In the Seattle area, the outbreak was smaller, and Snohomish County had just one case of measles. Still, the contagion containment efforts were statewide and can be drawn on now.

Federal health officials have been advising health care workers to take “airborne precautions” and wear protective gear if they are near a patient who is under investigation for the new coronavirus. At the moment, it appears considerably less dangerous than the flu.

“At this time in the U.S., this virus is not spreading in the community,” said Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, at a news conference.

The Washington patient was diagnosed after samples were sent to CDC headquarters in Atlanta. The CDC has developed a test to diagnose the new coronavirus.

“We are refining the use of this test so we can provide optimal guidance to states and laboratoriums on how to use it,” said Messonnier. The agency plans to distribute those to public health labs around the country “as fast as possible” in the coming weeks, she said.

“There are a lot of unknowns,” said Janet Baseman, a professor of epidemiology at the University of Washington. “The best thing public health can do now is assume that it will be similar to other coronavirus outbreaks we have seen in recent years until proven otherwise.”

“Being overprepared is the name of the game,” she said.

With only one case of the coronavirus from China confirmed so far in Washington, Baseman said it’s much easier for public health workers to do contact tracing than it was last year when they faced the measles outbreak, which included multiple cases.

“It was a really different situation because there were also a lot more exposed people,” said Baseman.

This story is part of a partnership between NPR and Kaiser Health News.