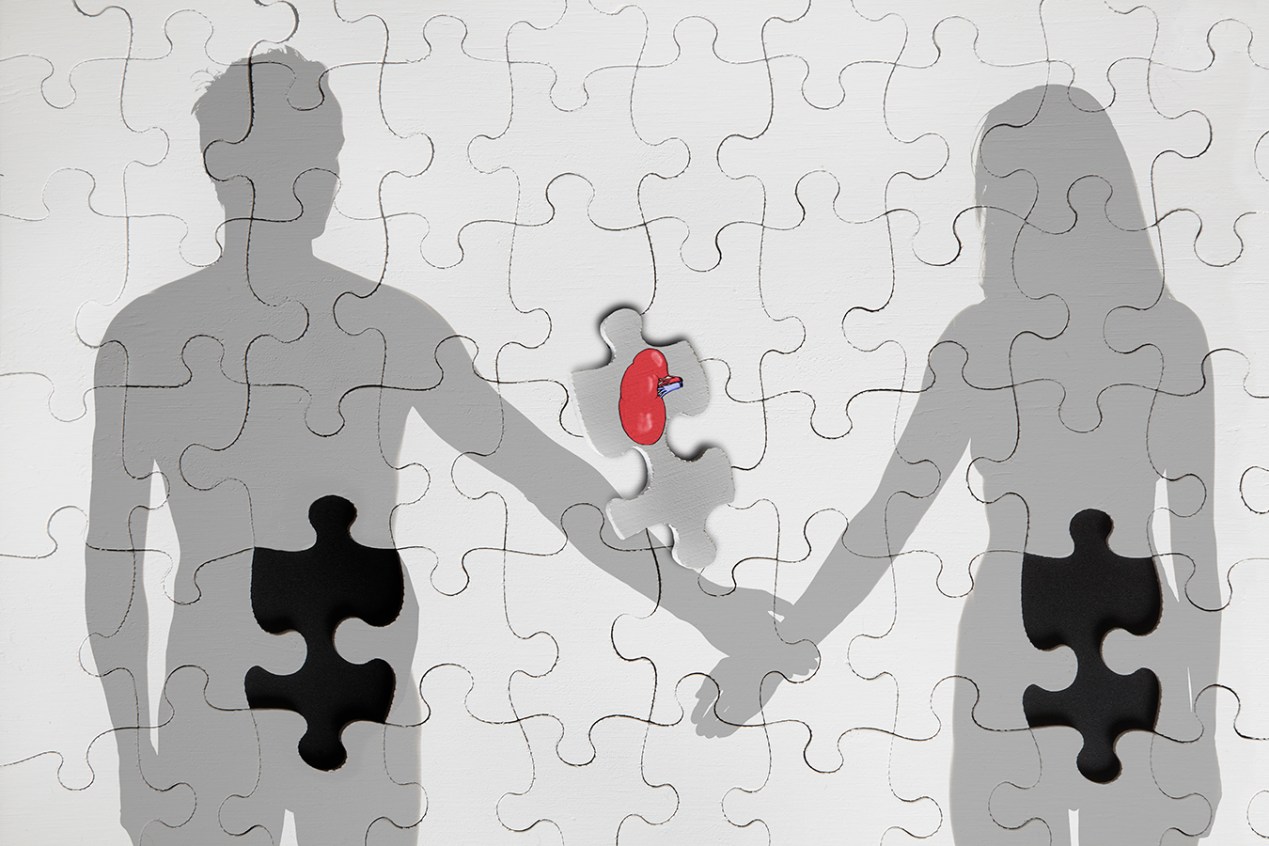

The nation’s first kidney transplant from a living HIV-positive donor to another HIV-positive person was successfully performed Monday by doctors at a Johns Hopkins University hospital.

By not having to rely solely on organs from the deceased, doctors may now have a larger number of kidneys available for transplant. Access to HIV-positive organs became possible in 2013, and surgeries have been limited to kidneys and livers.

“It’s important to people who aren’t HIV-positive because every time somebody else gets a transplant and gets an organ and gets off the list, your chances get just a little bit better,” said Dr. Sander Florman, director of the Recanati/Miller Transplantation Institute at Mount Sinai in New York.

Nina Martinez, 35, is the living donor. She donated her kidney to an anonymous recipient after the friend she had hoped to give it to died last fall. Martinez acquired HIV when she was 6 weeks old through a blood transfusion and was diagnosed at age 8.

In a news conference Thursday, Martinez said that even after her friend died, she wanted to carry on in honoring him by donating her kidney and making a statement.

“I wanted to show that people living with HIV were just as healthy. Someone needed that kidney, even if it was a kidney with HIV. I very simply wanted to show that I was just like anybody else,” said Martinez.

Johns Hopkins said that Martinez was being discharged Thursday from the hospital. The anonymous recipient is in stable condition and will likely be discharged in the next couple of days.

Since 1988, doctors have transplanted at least 1,788 kidneys and 507 livers — both HIV-positive and HIV-negative organs — to patients with HIV, according to the United Network for Organ Sharing, a private nonprofit that manages the nation’s organ transplant waiting list. All the HIV-positive organs came from recently deceased people.

Johns Hopkins Medicine was the first to perform the initial HIV-to-HIV transplant from a deceased donor in the U.S. in 2016.

Dr. Dorry Segev, one of the Johns Hopkins surgeons who performed the organ transplant, said the surgery was no different than any other live donor transplant that he has done because Martinez’s HIV was so well-controlled by antiretroviral medication. He said Johns Hopkins has already been receiving calls from people living with HIV who want to be living organ donors.

“This is not only a celebration of transplantation, but also HIV care,” said Segev during the news conference.

People living with HIV have faced challenges participating in organ transplants as recipients and donors. Organ transplant centers initially hesitated to give these patients organs for fear of inadvertently infecting them with the virus or accelerating the onset of AIDS in the recipient. Physicians thought the medicines given to prevent organ rejection — which suppress the immune system — could allow HIV to attack more of the body’s cells, unchecked.

Yet, some centers assumed the risks and performed these procedures. “There were no rules,” Florman said. “That was the wild west.”

Transplants slowly increased as more evidence proved liver and kidney recipients with HIV survived at rates similar to patients without the virus. But by the 2000s, the medical community and advocates wanted more. Prospective donors with HIV could not donate their organs, as Congress had banned the practice.

The push for change resulted in the HIV Organ Policy Equity Act, known as the HOPE Act, in 2013. This federal law allowed organ transplants between people with HIV in clinical trials. The legislation drastically cuts the waiting time for recipients with HIV who are willing to accept an organ from a person with the virus from years to months, Florman said. Only patients with HIV are allowed to accept these organs.

Kidney and liver transplants began under the HOPE Act three years after the legislation passed. As of March 24, 116 HOPE Act kidney and liver transplants have taken place.

UNOS does not track HIV status information for transplant candidates on its waiting list. But, as of March 8, 221 registrants have indicated they would be willing to accept a kidney or liver from a donor who has HIV.

Under the HOPE Act, recipients and living donors must meet requirements like undetectable levels of HIV, a normal CD4 count — an important type of white blood cell — and no opportunistic infections. Deceased donors are highly scrutinized to make sure they do not have a strain of HIV that is difficult to manage or treat, Florman said.

Researchers are seeking to expand the HOPE Act protocol to other organs. Dr. David Klassen, the chief medical officer for UNOS, said the Johns Hopkins living donor transplant opens up a promising new avenue for both organ recipients and donors living with HIV.

“As we accumulate more safety data, I think it is possible that the HOPE Act could become a standard of care possibly in the next couple of years,” said Klassen. “At some point, I think this will move into the mainstream.”

Some view the legislation not only as an avenue to advance medicine, but also to challenge how people perceive HIV. The ability to donate an organ implies a certain level of health that was once thought impossible in people living with HIV, said Peter Stock, professor of surgery at the University of California-San Francisco and one of the pioneering surgeons in HIV organ transplants.

“It used to be a death sentence,” he said of HIV. “And now we’re transplanting them.”

Dr. Christine Durand, another Johns Hopkins physician involved in the organ transplant, encouraged those living with HIV to sign their organ donor cards and contact their local transplant center if they’re interested in living donation.

“I am hoping this leads to a ripple effect,” said Durand. “And many people with HIV will be inspired to sign up as an organ donor as a result.”