[Update: On Dec. 5, 2025, a federal vaccine panel voted 8-3 to end the decades-long recommendation that all newborns receive a hepatitis B vaccine. The committee kept the recommendation that babies of mothers who test positive for the virus or whose status is unknown should be immunized soon after birth.]

Working out of a tribal-owned hospital in Anchorage, Alaska, liver specialist Brian McMahon has spent decades treating the long shadow of hepatitis B. Before a vaccine became available in the 1980s, he saw the virus claim young lives in western Alaskan communities with stunning speed.

One of his patients was 17 years old when he first examined her for stomach pain. McMahon discovered she had developed liver cancer caused by hepatitis B, just weeks before she was set to graduate from high school as valedictorian. She died before the ceremony.

McMahon thinks often of an 8-year-old boy who showed no signs of illness until he complained of pain from what turned out to be a rapidly growing tumor on his liver.

McMahon can still hear his voice.

“He was moaning in pain, saying, ‘I know I am going to die soon,’” he recalled. “We were all crying.” The boy died at home a week later.

The hepatitis B virus is transmitted through blood and bodily fluids, even in microscopic amounts, and the virus can survive on surfaces for a week. Like many of his patients, McMahon said, both children contracted hepatitis B at birth or in early childhood.

That outcome is now preventable. A birth dose of the vaccine, recommended for newborns since 1991, is up to 90% effective in preventing infection from the mother if given in the first 24 hours of life. If babies receive all three doses, 98% of them have immunity from the incurable virus, with the protection lasting at least 30 years.

In the communities of western Alaska, years of targeted testing and widespread vaccination efforts led to the number of cases plummeting.

“Liver cancer has disappeared in children,” McMahon said. “We haven’t seen a case since 1995. Nor do we have any children under 30 that have gotten infected that we know of.”

He worries those hard-won gains could soon be rolled back.

Pushing Back the Dose?

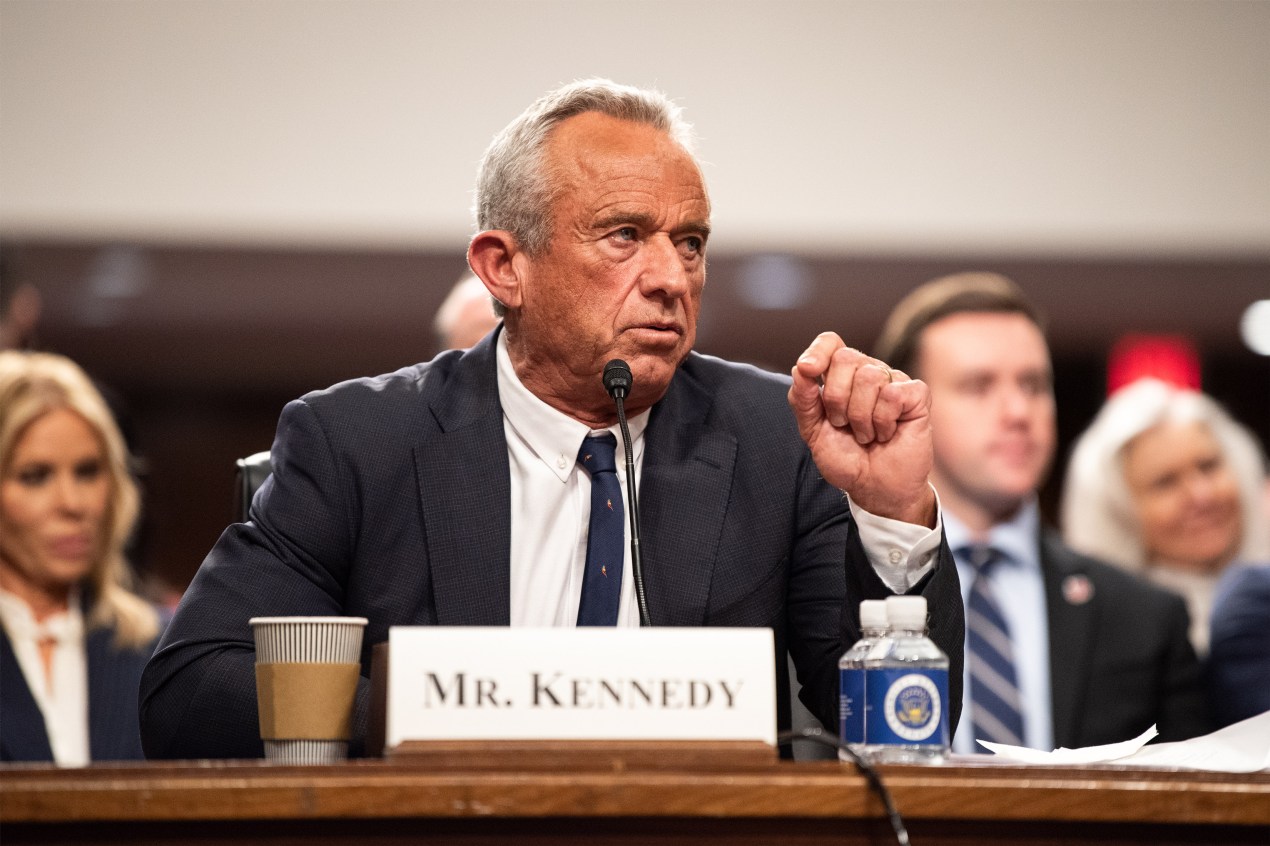

A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention vaccine advisory panel appointed by Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is scheduled to discuss and vote on the hepatitis B birth dose recommendation during its two-day meeting starting Dec. 4, potentially limiting children’s access.

On Tucker Carlson’s podcast in June, Kennedy falsely claimed that the hepatitis B birth dose is a “likely culprit” of autism.

He also said the hepatitis B virus is not “casually contagious.” But decades of research shows the virus can be transmitted through indirect contact, when traces of infected fluids like blood enter the body when people share personal items like razors or toothbrushes.

The committee’s recommendations carry weight. Most private insurers must cover the vaccines the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices endorses, and many state vaccination policies are directly linked to its guidelines.

Neither ACIP nor the CDC is regulatory. They cannot mandate immunizations. It’s up to states to do that. But keeping the recommendation for a hepatitis B vaccine at birth preserves the widest range of options for families. They can choose to vaccinate at birth, wait until later in childhood, or not vaccinate at all, and insurance will continue to cover the cost of the shot as long as it remains approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Two senior FDA officials — Commissioner Marty Makary and top vaccine regulator Vinay Prasad — suggested at the end of November that changes to the vaccine approval process may be coming. Vaccines must be approved by the FDA to be administered in the United States.

In internal agency emails obtained by PBS NewsHour and The Washington Post, Prasad questioned the routine practice of “giving multiple vaccines at the same time.” It’s not clear whether he was referring to combination vaccines that offer immunity against multiple diseases with a single shot. Three of the nine hepatitis B vaccines currently approved by the FDA are combination vaccines. The birth dose of the hepatitis B vaccine is given only as a stand-alone vaccine.

Contacted for comment, Health and Human Services spokesperson Emily Hilliard said in a statement that “ACIP will review the evidence at its meeting this week and issue recommendations based on gold standard, evidence-based science and common sense.”

‘Sowing Distrust’

If private insurers opt to still cover the shot, misinformation from the meeting still could lead families to falsely believe the vaccine could harm their babies, said Sean O’Leary, chair of the Committee on Infectious Diseases for the American Academy of Pediatrics and an assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

“Whatever comes out of this disaster of a meeting in December is going to be mainly designed around sowing distrust and spreading fear,” he said.

President Donald Trump, Kennedy, and some newly appointed ACIP members have mischaracterized how the liver disease spreads, ignoring or downplaying the risk of transmission through indirect contact. The hepatitis B virus is far more infectious than HIV. Unvaccinated people, including children, can get infected from microscopic amounts of blood on a tabletop or toy, even when the infected person is asymptomatic.

McMahon has cared for children who tested negative at birth and later became infected through indirect contact. In a study in the 1970s, nearly a third of such children went on to develop chronic hepatitis B without ever showing symptoms, he said.

“It’s a very infectious virus,” McMahon said. “That’s why giving everybody the birth dose is the best way to prevent it.”

The CDC recommends that all pregnant people be screened for hepatitis B, but it estimates that up to 16% are not tested and fall through the cracks. O’Leary and other experts say testing mothers for the virus shortly before or after delivery is unfeasible, because most hospitals lack the staff and resources.

The three-dose vaccine has a long track record of safety. Numerous studies show it is not associated with an increased risk of infant death, fever or sepsis, multiple sclerosis, or autoimmune conditions, and severe reactions are rare.

“We have an incredible safety profile,” O’Leary said. “No one expects to get in a car wreck, right? And yet we all put our seat belts on. This is similar.”

The CDC estimates that 2.4 million people in the U.S. have hepatitis B and that half do not know they are infected. The disease can range from an acute infection to a chronic one, often with few to no symptoms. If the disease is left untreated, it can lead to serious conditions such as cirrhosis, liver failure, and liver cancer. There is no cure.

Expert’s Advice to Parents: Talk to a Doctor

William Schaffner, a professor of preventative medicine at the Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and a former voting member of ACIP, said some parents struggle to understand why a healthy newborn needs a vaccine so soon after birth, especially for a virus they feel certain they don’t have and often wrongly associate only with risky behaviors. Those perceptions, he said, mix with declining trust in public health and rising skepticism about vaccines.

His advice to expectant parents who are on the fence is to talk to their doctor about the shots. Even if the pregnant woman has tested negative, he said, it’s still important to give the baby the birth dose, because false negatives are possible and because the virus can spread so easily from surface contact. Babies who receive the full vaccine series starting from birth have their chance of liver cancer reduced by 84%.

“If you wait a month and if the mom happens to be positive, or the baby picks it up from a caregiver, by that time the infection is established in that baby’s liver,” Schaffner said. “It’s too late to prevent that infection.”

He said that if fewer people get vaccinated, hepatitis B will circulate at higher rates in American communities and the risk of contracting the virus will rise for everyone who doesn’t get the shots.

And more hepatitis B cases could mean higher costs for patients and the broader health care system. The CDC estimates treating someone with a less severe form of the disease costs $25,000 to $94,000 per year. For patients who require a liver transplant, annual medical expenses can climb above $320,000, depending on their treatment.

Over the past 30 years, the main adverse events parents have reported from their babies receiving the birth dose have been fussiness and crying, both of which pass quickly. Schaffner said that’s a very strong safety profile — for a newborn vaccine with a track record of protecting babies from an incurable disease.

“The data are so clear about this,” Schaffner said. “A whole array now of other countries have initiated this program. They’ve modeled it on us.”