We’ve been here before: congressional Democrats and Republicans sparring over the future of the Affordable Care Act.

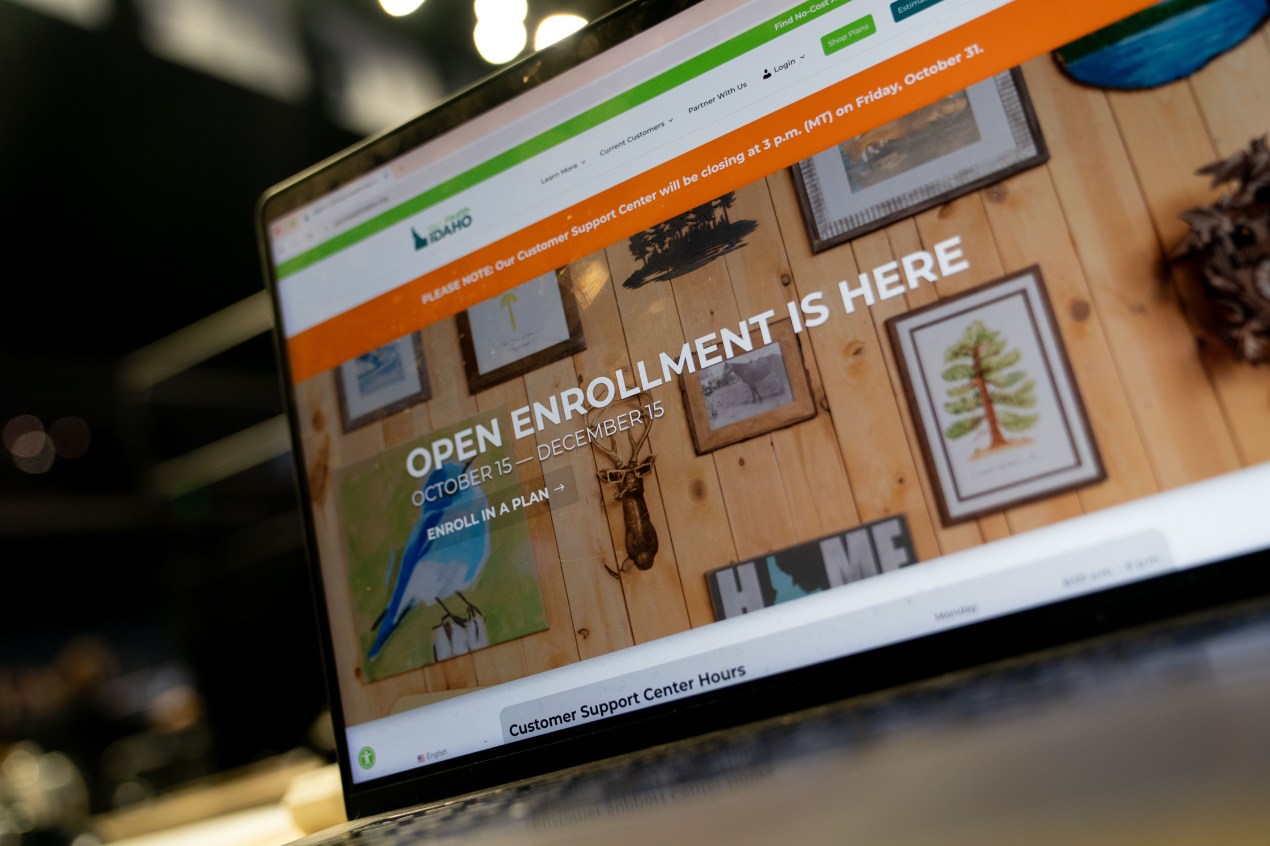

But this time there’s an extra complication. Though it’s the middle of open enrollment, lawmakers are still debating whether to extend the subsidies that have given consumers extra help paying their health insurance premiums in recent years.

The circumstances have led to deep consumer concerns about higher costs and fears of political fallout among some Republican lawmakers.

According to a KFF poll released in December, about half of current enrollees who are registered to vote said that if their overall health care expenses — copays, deductibles, and premiums — increased by $1,000 next year, it would have a “major impact” on whether they vote in next year’s midterm elections or which party’s candidate they support.

For those caught in the middle — including consumers and leaders of the 20 states, along with the District of Columbia, that run their own ACA marketplaces — the lack of action on Capitol Hill has led to uncertainty about what to do.

“Before I sign up, I will wait and see what happens,” said poll participant Daniela Perez, a 34-year-old education consultant in Chicago who says her current plan will increase to $1,200 a month from about $180 this year without an extension of the tax credits. “I’m not super hopeful. Seems like everything is in gridlock.”

In Washington, as part of the deal to end the recent government shutdown, a Senate vote was held Dec. 11 on a proposal to extend the subsidies. Another option, which was advanced by Republicans and included funding health savings accounts, was also considered. Neither reached the 60-vote mark necessary for passage.

On the House side, Speaker Mike Johnson plans to bring to the floor a narrow legislative package designed to “tackle the real drivers of health care costs.” It would include expanded access to association health plans and appropriations for cost-sharing reduction payments to stabilize the individual market and lower premiums. It would also increase transparency requirements for pharmacy benefit managers. Like the bill put forward by Republicans in the Senate it would not extend the ACA’s enhanced subsidies. Lawmakers are likely to vote on such an extension at some point.

In general, Democrats want to extend the life of the more generous subsidies, created in response to the covid pandemic. Those are set to expire at the end of the year. Republicans are split, with many balking at the cost of a straightforward extension, as well as the policy and political implications that might come with a vote to buttress Obamacare, which many have long viewed as public enemy No. 1.

And a few back various proposals that would extend the tax subsidies, fearing that failing to do so will result in political fallout in next year’s midterm elections.

The result is that differing policy positions are being advanced by lawmakers on both sides of the aisle and in both chambers of Congress.

The White House, though supportive of HSAs in principle, has not made clear its choice among the various Capitol Hill plans.

Meanwhile, the clock is ticking for shoppers. People needed to choose their ACA plan before Dec. 15 for coverage to begin Jan. 1. Open enrollment continues in most states until Jan. 15 for coverage beginning Feb. 1.

The marketplaces, too, must have contingency plans in case Congress intervenes. These adjustments could take days or weeks.

“We have a plan on the shelf” to go update the website, including notifying consumers of any changes, said Audrey Morse Gasteier, executive director of the Massachusetts Health Connector, a state-based ACA insurance marketplace.

Still, not many working days remain on Congress’ 2025 calendar, and “in many ways, it feels like they are farther apart than they were even a few months ago,” said Jessica Altman, executive director of Covered California, that state’s ACA marketplace.

Waiting for Numbers

Both Altman and Gasteier said it’s still too early to tell how final enrollment tallies will come out, but already there are indications of how sign-ups will compare with last year’s record high of about 24 million.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on Dec. 5 released figures from about the first month of open enrollment, showing 949,450 new sign-ups — people who did not have ACA coverage this year — across the federal and state marketplaces. That’s down a bit from approximately the same period last year, when there were 987,869 new enrollees by early December.

Up slightly, however, are returning customers who have already selected a plan for next year. That stands at about 4.8 million, according to CMS, compared with about 4.4 million at this time last year.

That initial finding — lower new enrollments but quicker action by some already covered — may reflect that “people who come back early in the enrollment period are those who need the coverage because they have a chronic condition or need something done,” said Sabrina Corlette, co-director of Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. “So they are more motivated in the front half.”

And the final number of federal marketplace enrollments takes time to shake out. “The rubber meets the road when people have to pay the first premium,” Corlette said. “With the federal marketplace, we won’t know that for some time.”

Some states have also released information from the first few weeks, with the caveat that many people may wait until mid-December or later to make coverage decisions. Affordability has emerged as a pressure point.

In Pennsylvania, for example, in the first six weeks of open enrollment there was a 16% decrease in people signing up for the first time compared with last year, according to data posted by Pennie, the state’s ACA insurance marketplace. For every one of those new enrollments, 1.5 existing customers canceled, Pennie reported.

There were some indicators that income is a factor: Most of those canceling earned 150% to 200% of the federal poverty level, or $23,475 to $31,300 for a single adult.

Most states automatically reenroll existing customers into the same or similar coverage for the following year. Letters and other notifications are sent to consumers, who then can let the coverage continue or go online during the open enrollment period to change their plan or cancel it.

California reported a 33% drop in new enrollments through Dec. 6. And Altman said she’s also seeing some other changes.

She said more people are opting for “bronze”-level plans, which have lower premium payments than “silver” or “gold” plans but also higher deductibles — the amount people have to pay before most insurance coverage kicks in.

Nationally, the average bronze-plan deductible will be $7,476 next year, while silver plans carry an average $5,304 deductible, according to KFF, a health information nonprofit that includes KFF Health News.

“That people are being forced to opt for plans with really high deductibles is a warning sign,” Altman said.

In Massachusetts, consumer calls to the state’s marketplace in the first month were up 7% over last year, Gasteier said.

Additionally, “our call centers are getting heartbreaking phone calls from people about how they can’t understand how they can possibly remain in coverage,” she said.

Detailing the Difference

If the enhanced tax credits expire, Obamacare subsidies will revert to pre-pandemic levels.

Households will pay a percentage of their income toward the premium, and a tax credit subsidy will cover the remainder, with the payment generally made directly to the insurer.

The enhanced subsidies reduced the amount of household income people had to pay toward their own coverage, with the lowest-income people paying nothing. Also, there was no upper limit on income to qualify — a particular point of criticism from Republicans. Still, in reality, some high earners don’t get a subsidy, because their premiums without it are less than what they are required to contribute.

Next year, without the more generous subsidies, those in the lowest income brackets will pay at least 2.1% of their household income toward their premiums, with the highest earners paying nearly 10%. No subsidies would be available for people earning more than four times the federal poverty level, which comes to $62,600 for an individual or $84,600 for a couple.

For those now shopping for coverage, that cap means a sharp increase in coverage costs. Not only have insurers raised premiums, but now that group’s subsidies have been cut entirely.

“They said, based on our salary, we don’t qualify,” said Debra Nweke, who, at 64, is retired, while her husband, 62, still works. They live in Southern California and are looking at coverage going from $1,000 a month this year to $2,400 monthly next year if they stay in the same ACA plan. “How can you have health insurance that is more than your rent?”

Senate Majority Leader John Thune said in early December that Republicans want to find a solution that will lower health care costs, but not one with “people who are making unlimited amounts of money being able to qualify for government subsidies.” He also objected to granting free coverage to those at the lower end of the income scale.

Even those getting subsidies say they are feeling the pinch.

“Our prices are going up, but even at that, I don’t have any other options,” said Andrew Schwarz, a 38-year-old preacher in Bowie, Texas, who gets ACA coverage for himself and his wife. His three children are on a state health insurance program because the family qualifies as low-income. Both Schwarz and Nweke took part in the KFF poll.

Schwarz’s coverage is going from $40 a month this year to $150 monthly next year, partly because he chose a plan with a lower deductible than some of the other options.

Schwarz said that while the health system overall has many problems, Obamacare has worked out for his family. They’ll just have to take the additional cost out of somewhere else in the family budget, he said.