For Tammy Rainey, finding a health care provider who knows about gender-affirming care has been a challenge in the rural northern Mississippi town where she lives.

As a transgender woman, Rainey needs the hormone estrogen, which allows her to physically transition by developing more feminine features. But when she asked her doctor for an estrogen prescription, he said he couldn’t provide that type of care.

“He’s generally a good guy and doesn’t act prejudiced. He gets my name and pronouns right,” said Rainey. “But when I asked him about hormones, he said, ‘I just don’t feel like I know enough about that. I don’t want to get involved in that.’”

So Rainey drives around 170 miles round trip every six months to get a supply of estrogen from a clinic in Memphis, Tennessee, to take home with her.

The obstacles Rainey overcomes to access care illustrate a type of medical inequity that transgender people who live in the rural U.S. often face: a general lack of education about trans-related care among small-town health professionals who might also be reluctant to learn.

“Medical communities across the country are seeing clearly that there is a knowledge gap in the provision of gender-affirming care,” said Dr. Morissa Ladinsky, a pediatrician who co-leads the Youth Multidisciplinary Gender Team at the University of Alabama-Birmingham.

Accurately counting the number of transgender people in rural America is hindered by a lack of U.S. census data and uniform state data. However, the Movement Advancement Project, a nonprofit organization that advocates for LGBTQ+ issues, used 2014-17 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data from selected ZIP codes in 35 states to estimate that roughly 1 in 6 transgender adults in the U.S. live in a rural area. When that report was released in 2019, there were an estimated 1.4 million transgender people 13 and older nationwide. That number is now at least 1.6 million, according to the Williams Institute, a nonprofit think tank at the UCLA School of Law.

One in 3 trans people in rural areas experienced discrimination by a health care provider in the year leading up to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Report, according to an analysis by MAP. Additionally, a third of all trans individuals report having to teach their doctor about their health care needs to receive appropriate care, and 62% worry about being negatively judged by a health care provider because of their sexual orientation or gender identity, according to data collected by the Williams Institute and other organizations.

A lack of local rural providers knowledgeable in trans care can mean long drives to gender-affirming clinics in metropolitan areas. Rural trans people are three times as likely as all transgender adults to travel 25 to 49 miles for routine care.

In Colorado, for example, many trans people outside Denver struggle to find proper care. Those who do have a trans-inclusive provider are more likely to receive wellness exams, less likely to delay care due to discrimination, and less likely to attempt suicide, according to results from the Colorado Transgender Health Survey published in 2018.

Much of the lack of care experienced by trans people is linked to insufficient education on LGBTQ+ health in medical schools across the country. In 2014, the Association of American Medical Colleges, which represents 170 accredited medical schools in the United States and Canada, released its first curriculum guidelines on caring for LGBTQ+ patients. As of 2018, 76% of medical schools included LGBTQ health themes in their curriculum, with half providing three or fewer classes on this topic.

Perhaps because of this, almost 77% of students from 10 medical schools in New England felt “not competent” or “somewhat not competent” in treating gender minority patients, according to a 2018 pilot study. Another paper, published last year, found that even clinicians who work in trans-friendly clinics lack knowledge about hormones, gender-affirming surgical options, and how to use appropriate pronouns and trans-inclusive language.

Throughout medical school, trans care was only briefly mentioned in endocrinology class, said Dr. Justin Bailey, who received his medical degree from UAB in 2021 and is now a resident there. “I don’t want to say the wrong thing or use the wrong pronouns, so I was hesitant and a little bit tepid in my approach to interviewing and treating this population of patients,” he said.

On top of insufficient medical school education, some practicing doctors don’t take the time to teach themselves about trans people, said Kathie Moehlig, founder of TransFamily Support Services, a nonprofit organization that offers a range of services to transgender people and their families. They are very well intentioned yet uneducated when it comes to transgender care, she said.

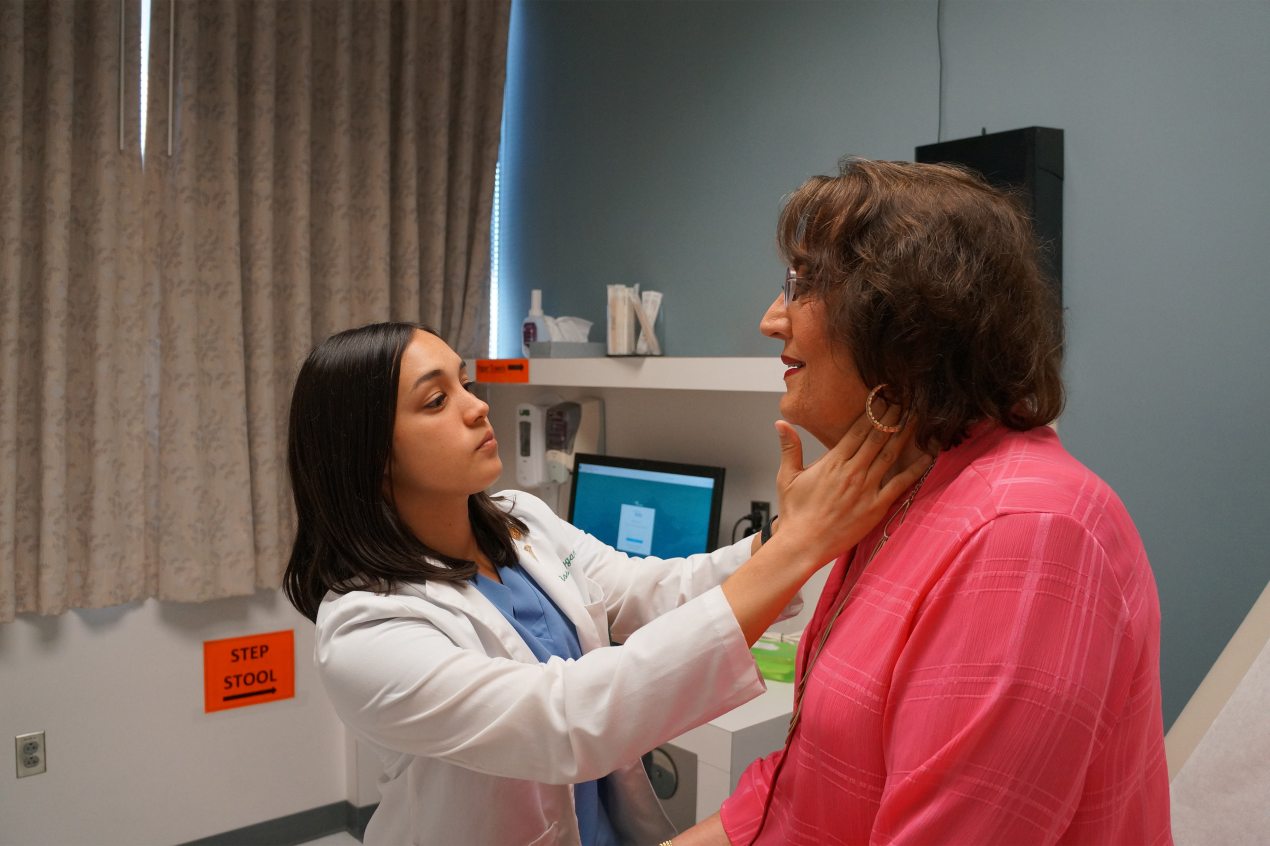

Some medical schools, like the one at UAB, have pushed for change. Since 2017, Ladinsky and her colleagues have worked to include trans people in their standardized patient program, which gives medical students hands-on experience and feedback by interacting with “patients” in simulated clinical environments.

For example, a trans individual acting as a patient will simulate acid reflux by pretending to have pain in their stomach and chest. Then, over the course of the examination, they will reveal that they are transgender.

In the early years of this program, some students’ bedside manner would change once the patient’s gender identity was revealed, said Elaine Stephens, a trans woman who participates in UAB’s standardized patient program. “Sometimes they would immediately start asking about sexual activity,” Stephens said.

Since UAB launched its program, students’ reactions have improved significantly, she said.

This progress is being replicated by other medical schools, said Moehlig. “But it’s a slow start, and these are large institutions that take a long time to move forward.”

Advocates also are working outside medical schools to improve care in rural areas. In Colorado, the nonprofit Extension for Community Health Outcomes, or ECHO Colorado, has been offering monthly virtual classes on gender-affirming care to rural providers since 2020. The classes became so popular that the organization created a four-week boot camp in 2021 for providers to learn about hormone therapy management, proper terminologies, surgical options, and supporting patients’ mental health.

For many years, doctors failed to recognize the need to learn about gender-affirming care, said Dr. Caroline Kirsch, director of osteopathic education at the University of Wyoming Family Medicine Residency Program-Casper. In Casper, this led to “a number of patients traveling to Colorado to access care, which is a large burden for them financially,” said Kirsch, who has participated in the ECHO Colorado program.

“Things that haven’t been as well taught historically in medical school are things that I think many physicians feel anxious about initially,” she said. “The earlier you learn about this type of care in your career, the more likely you are to see its potential and be less anxious about it.”

Educating more providers about trans-related care has become increasingly vital in recent years as gender-affirming clinics nationwide experience a rise in harassment and threats. For instance, Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Clinic for Transgender Health became the target of far-right hate on social media last year. After growing pressure from Tennessee’s Republican lawmakers, the clinic paused gender-affirmation surgeries on patients younger than 18, potentially leaving many trans kids without necessary care.

Stephens hopes to see more medical schools include coursework on trans health care. She also wishes for doctors to treat trans people as they would any other patient.

“Just provide quality health care,” she tells the medical students at UAB. “We need health care like everyone else does.”