Rep. Kevin McCarthy, the number three Republican in the U.S. House of Representatives, has a very clear record on the Affordable Care Act. He has repeatedly called for its defeat and was one of the co-sponsors of the January repeal measure that easily passed the House but died in the Senate.

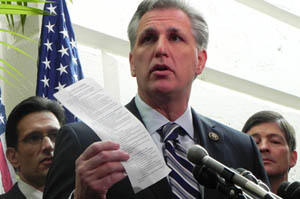

House Majority Whip Kevin McCarthy, R-Calif., discusses H.R. 2, a bill to repeal the 2010 health law, during a Jan. 18 press conference (Photo by Medill DC via Flickr).

But back in his hometown of Bakersfield, Calif., local officials are welcoming one aspect of the health overhaul law. Earlier this year, the Kern County Board of Supervisors — all Republicans — voted to accept federal money to expand insurance coverage for low-income adults.

The federal law extends Medicaid coverage to millions of Americans in 2014, including childless adults. But with permission – and dollars – from the federal government, California started the expansion early.

Indeed, all 58 counties in California, except Fresno, are offering care to more poor residents, which includes the most conservative counties, like Modoc, Orange, San Diego and Kern.

Expanding coverage to the 63,000 uninsured county residents couldn’t come too soon for Paul Hensler, the administrator in charge of the county’s public hospital, Kern Medical Center.

“Our proposal was to expand coverage to those that don’t have coverage and reduce the cost of care and improve outcomes,” he said. Because the county is now assigning uninsured, low-income adults — who up until now have been excluded from Medicaid – to primary care clinics, their chronic diseases are managed better, keeping them out of his emergency room.

Surprisingly though, the roll-out of what conservatives derisively call “Obamacare” has largely gone unnoticed in Bakersfield.

“This is one of those things that is being implemented under the radar,” says Ken Mettler, who helped found the Tea Party in Bakersfield. A dogged critic of the local Board of Supervisors, even Mettler wasn’t aware what the county was doing until asked about it by a reporter.

He says elected officials vigorously denounce the federal health law, but then are all too eager to roll it out.

“They always have to make this leap of logic that if we don’t take the money somebody else will. We will not be able to provide services that we’re mandated to provide,” Mettler said. “No one has the political courage to stand up and say, ‘look, this is wrong on all levels and if we don’t take a stand, who will?’”

But Supervisor Ray Watson, who has represented Kern County’s west side for nine years, says the move was necessary because California law mandates that counties offer basic medical care and emergency services to impoverished residents.

“We are on the hook already,” says Watson. “We get some funding, but it’s far from what is required to care for those people.”

Counties – which have suffered mightily in the economic downturn – are often on the losing end. When the economy slows and people lose their health insurance, demand for county services goes up. Watson, a Republican, says it’s a matter of fairness, not ideology.

“We have one of the lowest rates of returns of federal dollars,” Watson says, referring to the ratio of dollars paid in federal taxes to dollars returned to Kern County. “It’s not fair for our taxpayers to have to pay the burden of indigent care. … If it’s a policy of the government to make sure that we don’t have people suffering in the streets then the government needs to find a way to pay for it.”

Watson is no fan of the federal health law, but he says the uninsured do need some basic level of care and moving them away from the emergency room and into regular primary care makes sense.

Republican Supervisor Karen Goh, who represents Kern County’s poorest neighborhoods, agrees.

“We have obesity. We have high blood pressure. We have just about every bad thing,” says Goh. “Getting people to have those regular checkups. That’s a very important thing in a community of poverty.”

Goh is of two minds when it comes to the federal health law. She says it’s unfair that sick people can’t get health insurance, but she also opposes mandates on private businesses. She thinks local church groups – including one that runs a mobile van called the Jesus Shack – are filling some of the need. But, it seems implausible church groups could do it all.

Still, to some conservative voters in Kern County, the supervisors’ support of the early Medicaid expansion – explicitly stated or not – is tantamount to an endorsement of the federal health law. And that, says Republican political consultant Stan Harper, is a liability.

“I would say in Kern County and the immediate surrounding counties that if a candidate was out to run and support ObamaCare they would lose,” Harper said.

It’s unclear how the county’s Medicaid expansion might play in any future elections. Despite repeated requests for an interview, Rep. McCarthy would only say that in theory moving people into preventive programs was a good idea, but he didn’t comment specifically on the efforts underway in Kern County.

The Bakersfield Tea Party says they’re paying attention now, and they’ll be looking to back candidates, even on the county level, that want to get rid of the federal health entirely.