A 58-year-old Maryland woman breaks her ankle, develops a blood clot and, unable to find a doctor to monitor her blood-thinning drug, winds up in an emergency room 30 times in six months. A 55-year-old Mississippi man with severe hypertension and kidney disease is repeatedly hospitalized for worsening heart and kidney failure; doctors don’t know that his utilities have been disconnected, leaving him without air conditioning or a refrigerator in the sweltering summer heat. A 42-year-old morbidly obese woman with severe cardiovascular problems and bipolar disorder spends more than 300 days in a Michigan hospital and nursing home because she can’t afford a special bed or arrange services that would enable her to live at home.

These patients are among the 1 percent whose ranks no one wants to join: the costly cohort battling multiple chronic illnesses who consumed 21 percent of the nearly $1.3 trillion Americans spent on health care in 2010, at a cost of nearly $88,000 per person. Five percent of patients accounted for 50 percent of all health-care expenditures. By contrast, the bottom 50 percent of patients accounted for just 2.8 percent of spending that year, according to a recent report by the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

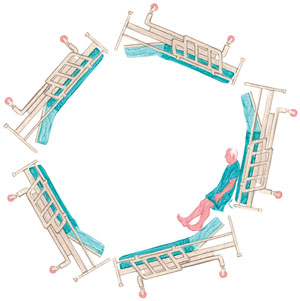

Sometimes known as super-utilizers, high-frequency patients or frequent fliers, these patients typically suffer from heart failure, diabetes and kidney disease, along with a significant psychiatric problem. Some are Medicare patients unable to afford the many drugs needed to manage their chronic health problems. Others are younger “dual eligibles” who qualify for Medicare and Medicaid, and who often bounce from emergency room to emergency room, struggling with substance abuse, homelessness and related medical conditions. Still others have private health insurance.

Nearly all wind up in emergency rooms because they have enormous difficulty navigating the increasingly fragmented, complicated and inflexible health-care system. Because of lack of alternatives or force of habit, they use hospitals, often several in the same city, for care that could be provided far more cheaply and effectively in outpatient settings. Many suffer from the phenomenon known as “extreme uncoordinated care.”

In the past few years, efforts to lower costs and improve care have proliferated. In Ann Arbor, Mich., two programs at the University of Michigan Health System assign specialized case managers to super-users, some of whom have been in the ER more than 100 times in a year. In a largely rural swath of central Pennsylvania, Geisinger Health System enrolls elderly Medicare patients in its Proven Health Navigator program, calling them after they leave the hospital and providing heart failure patients with scales that transmit data to nurses: Sudden weight gain can signal a problem. In the Washington area, a program sponsored by Medical Mall Health Services — a program founded by civil rights activist and physician Aaron Shirley that targets medically underserved patients — provides home visits and helps arrange services for newly discharged patients.

“We’ve seen situations where for want of a $20 cab ride to get to dialysis, a patient ended up with an emergency hospitalization costing $20,000,” said Tim McNeill, chief operating officer of Medical Mall, which is headquartered in Jackson, Miss.

Most programs are modeled on an approach pioneered by Denver geriatrician and MacArthur Foundation “genius grant” winner Eric Coleman, whose Care Transitions program has been widely adopted and embraced by Medicare. In addition to a patient’s medical and mental health needs, these efforts focus on the social determinants of health including income, education and community support, low levels of which often trigger unnecessary readmissions.

More effectively managing the 1 percent is “a huge problem for us and for the health-care system in general,” said surgeon Carnell Cooper, vice president of medical affairs for Prince George’s Hospital Center, where more than 50 percent of patients are uninsured or underinsured, one of the highest rates in Maryland. “We are well aware from a quality perspective that we have to work on decreasing readmissions.”

100 ER Visits

The problem is receiving increasingly urgent attention from hospitals and insurance companies, which are facing pressure to deliver better and more-cost-effective care. The Affordable Care Act is ramping up penalties levied on hospitals for certain Medicare patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Hospitals have traditionally made more money readmitting patients than trying to prevent them from bouncing back. A recent study by researchers at Yale School of Medicine found that only a third of 400 elderly patients were discharged with a follow-up doctor’s appointment and 25 percent were handed instructions written in impenetrable medical jargon.

Insurers are also scrambling. They are expected to enroll millions of new customers under the law but can no longer control costs by imposing lifetime expenditure caps or refusing to cover preexisting conditions. The law also creates accountable care organizations — groups of doctors, hospitals and clinics – that pool resources to treat Medicare patients more effectively and share in the savings.

“Having a coordinated care plan is crucial,” said Susan Kosman, director of nursing for Aetna, which has linked previously separate mental health and medical teams to more effectively manage the cases of super-utilizers.

“We do a significant amount of sorting out the chaos in the system,” said internist Brent Williams, medical director of the University of Michigan’s Complex Care Management Program. Teams of doctors, nurses and case managers spend much of their time trying to bridge the chasm between inpatient and outpatient treatment systems, Williams said, each of which has its own set of rules and incentives.

After devising a coordinated plan for both inpatient and outpatient treatment, case managers follow patients, sometimes for several years, even accompanying them to doctors’ appointments, helping them obtain food or furniture and connecting them with community resources. A recent JAMA study found that the program decreased annual spending on a group of dual eligible patients by $2,500 per patient. Sometimes the savings are greater: Williams said that the 42-year-old severely obese patient who in 2011 spent all but 38 days as an inpatient is living at home and has had no hospitalizations so far this year.

A related program, which initially focused on the 14 top users of the emergency department at the Ann Arbor hospital, saved $1 million in 2011, according to Timothy Peterson, director of the ED Complex Care Program. “It’s not hard when someone’s been in the ER 100 times,” he said. “What most of these folks need is somebody who has the time to look at their case in a holistic way.”

Health Connect, the program sponsored by Medical Mall Health Services, is working with patients at Prince George’s Hospital Center and four others in the District and Maryland. So far, about 2,000 patients have been invited to enroll in the voluntary program, and more than 95 percent of them have done so.

The program is open to patients with one or more chronic diseases: sickle cell anemia, heart failure, diabetes and kidney disease. Many patients also have a mental health problem, including depression. A Medical Mall nurse meets patients in the hospital at least 48 hours before discharge to plan home care and try to plug gaps, such as a lack of transportation to follow-up medical appointments. Once home, patients receive a series of phone calls and at least one visit in the month after discharge. The goal is to make sure that prescriptions have been picked up and that a patient has an appointment with a doctor within seven days and a way to get there.

Between July and November 2012, readmissions to the Prince George’s County hospital within 30 days of discharge dropped 34 percent, according to Medical Mall’s McNeill, from 284 to 186. “The success has been significant,” said hospital vice president Cooper.

No Phone, No Follow-Up

One recent Friday, Michael Fonju, his eyes glued to his smartphone as he punches up driving directions, strides to his beige Chevy in the parking garage of Providence Hospital, a low-slung red brick facility in a leafy corner of Northeast Washington.

Since March, Fonju, a 27-year-old community health worker for Medical Mall who is trained as a respiratory therapist, has followed patients discharged from Providence. His caseload averages about 50 patients, most of them older than 55, who live nearby or in neighboring Prince George’s County. The biggest hurdle, Fonju said, is connecting with them: One-third don’t have a working phone. Participants are dropped from the program after three failed attempts to reach them.

First stop is the apartment of 70-year-old Louis Cunningham, sent home two weeks earlier after an eight-day stay for double pneumonia. In addition to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, he has high blood pressure and diabetes.

A tall, imposing man newly tethered to an oxygen tank, Cunningham tells Fonju that he has seen his primary care doctor; his wife has filled his prescriptions and his oxygen is working fine.

Fonju checks the tank and then asks Cunningham to demonstrate how he uses a new inhaler. “You know your stuff,” Fonju quips approvingly. Cunningham, looking pleased, said that other than a nicotine craving, he feels fine. A smoker for 60 years, he hasn’t had a cigarette for 15 days.

Next stop is a dimly lit brick rowhouse a mile away. Its 56-year-old occupant has been at Providence twice in the past month for severe shortness of breath. She hands Fonju a battered plastic bag containing the 15 medicines she takes each day to treat hypertension, bipolar disorder, HIV, asthma, COPD and heart failure.

Fonju examines her pill bottles, making sure they correspond to her records. “Why do you have so much lithium?” he asks with concern, referring to one of three psychiatric drugs she takes. “Are you getting your levels checked?” Lithium requires regular blood tests to prevent serious, even fatal, side effects; too much, he tells her, can be toxic.

“Oh, lithium can be toxic?” she asks, looking puzzled.

He asks if she has a scale. One is being delivered the next day, she tells Fonju.

“Make sure you write down your weight every day and take it with you to the doctor,” he reminds her, heading out the door and on to his next patient.