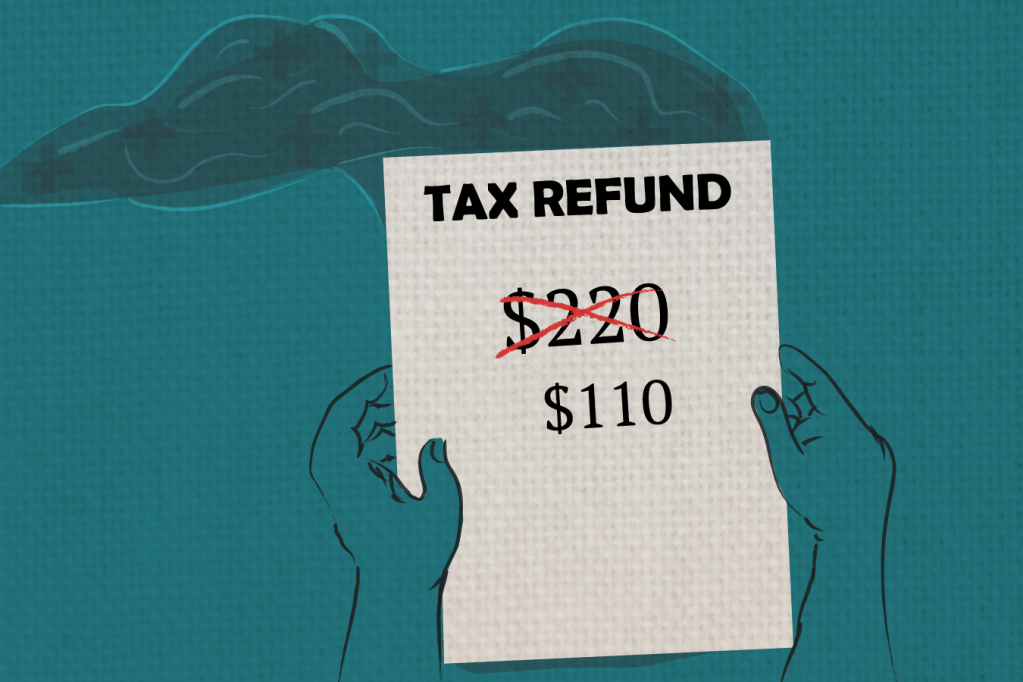

The notice from the Virginia tax department puzzled a Charlottesville couple last October. It said their state income tax refund had been reduced because of an outstanding medical debt to the University of Virginia Medical Center. Instead of $220, they got $110.

Mystified, they contacted UVA for details about the unpaid bill. The answer astonished them. The medical center had asked the tax department to withhold the money for medical care their son received in 2001 and 2002.

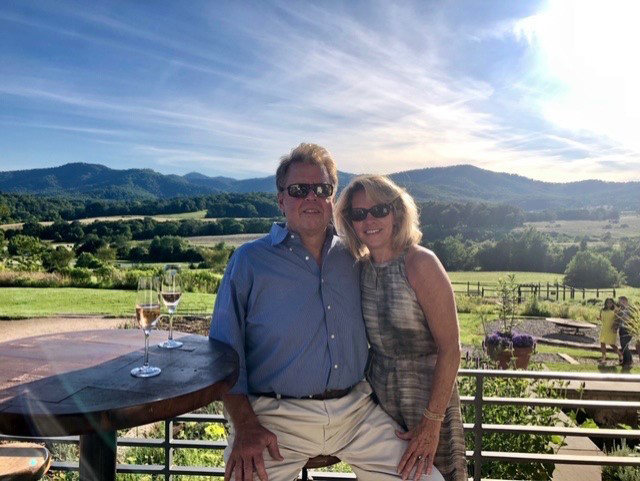

Jane Collins and Anthony Blow received a notice last year from the Virginia tax department, which reduced their state income tax refund to offset outstanding medical debt.(Courtesy of Jane Collins)

“The amount is not the issue; it’s this whole idea that you can go after something that is so old,” said Jane Collins. “Maybe technically you are entitled to that money, but do you mean to tell me you can go into the deep recesses of your computer and now you’re going to take this?”

Initially, Collins couldn’t remember what the bill was for, and she no longer had paper records from nearly two decades ago.

According to financial documents the hospital sent Collins and her husband, Anthony Blow, late last year, the bills relate to three hospitalizations for their son, who was born prematurely and frequently hospitalized as a child.

Collins believes the 2001 hospital visits are probably related to a shunt her son had when he was 3 to relieve fluid buildup in his brain. She’s uncertain what the 2002 charges are for. The computer printouts she received from UVA list service codes and billed charges but don’t describe why he was hospitalized.

“I’m utterly confused by all of this,” said Collins, whose family is covered by the same employer plan they had then. “Eighteen years later, I don’t remember disputing anything about the bills.”

A spokesperson for the health system said patient privacy laws prohibit them from commenting on specific cases.

Virginia is one of at least a dozen states that can dock residents’ income tax refunds to pay delinquent medical debts, according to Richard Gundling, a senior vice president for the Healthcare Financial Management Association, an organization for finance professionals. In Virginia, state-affiliated hospitals like the University of Virginia Medical System and Virginia Commonwealth University Health System generally first attempt to collect money owed to them directly or by enlisting a collection agency.

If those efforts fail, they send the claims to the state tax department’s Set-Off Debt Collection Program. The tax department uses Social Security numbers to electronically match claims submitted by the hospitals with individual income tax refunds. When the system finds a match, it withholds all or part of the refund and sends it to the hospital.

In fiscal 2018, Virginia collected $68 million in individual debts through the program, a figure that includes medical bills and other types of debt owed to state and local government agencies and state courts, among others.

It’s a controversial way to collect medical debt, especially for care delivered decades ago.

“This gives a whole new meaning to surprise medical bills,” said Mark Rukavina, business development manager at Community Catalyst, a consumer advocacy organization. “Digging up a bill that’s 20 years old and informing someone that they owe it by attaching their tax refund is not good policy.”

State laws prohibit private collection agencies from suing consumers after a specified period of time, often three to six years. The laws don’t extinguish the debt, but they protect consumers from being taken to court many years later, when documents may be lost and memories fuzzy.

But there’s no similar time limit for going after Virginia consumers’ tax refunds through the setoff program.

“[This] hospital is an agency of the commonwealth and the statute of limitations doesn’t apply to the commonwealth,” said Caroline Klosko, an attorney at the Legal Aid Justice Center in Charlottesville. Klosko said she worked with a client who faced a similar refund capture by UVA for a medical debt that was six years old.

In addition to the age of the debt, concerns over whether the amount billed is accurate are often legitimate.

What if people are charged too much in the first place? Federal law requires nonprofit hospitals to have patient financial assistance policies and to publicize them widely. For-profit hospitals generally seem to have similar programs, said Rukavina. But income standards and other requirements to qualify for discounted or free care vary widely and may not be easy for patients to find.

A new state law will prohibit UVA and VCU from taking consumers’ tax refunds to satisfy medical debts unless the health systems have determined that patients aren’t eligible for their financial assistance programs or Medicaid, the state-federal health insurance program for low-income people.

UVA screens people routinely for financial assistance and Medicaid eligibility, according to spokesperson Eric Swensen. Every year, the health system helps roughly 3,500 people qualify for Medicaid or Family Access to Medical Insurance Security, a program for children whose families earn too much for regular Medicaid, he said.

If someone has an overdue bill with UVA, the health system turns to the refund setoff program as a last resort after all other options, including establishing interest-free payment plans, have been exhausted, Swensen said. In 2019, UVA received $4 million from tax refunds for delinquent medical debt, according to Swensen. Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center collected approximately $7.7 million through the debt setoff program in 2019, according to spokesperson Laura Rossacher.

Collins said that she and her husband knew nothing about their debt until they got their smaller-than-expected “tax relief refund” last fall, along with a notice directing them to contact UVA if they had questions. (Under a 2019 state law, Virginia taxpayers were eligible to receive a one-time tax relief refund of up to $110 for individuals and $220 for married couples who file their taxes jointly.)

She said the couple had received state tax refunds in the years since this care was provided.

Swensen said that, in general, once a patient’s outstanding balance is sent to the state’s setoff program, “we are required to resubmit that balance to the state database each year until the patient pays their outstanding balance or the outstanding balance is satisfied through the debt setoff program.”

“If a patient had previous tax refunds that were not assessed, we are unsure why this happened,” he said.

A patient financial services representative at UVA told Collins the health system had sent billing statements, as well as final notices informing the couple that their accounts were being referred to collections. UVA also said it had notified them that the accounts would be reported to the state Department of Taxation.

Collins said that they never received those notices but that after their tax refund was withheld, they did receive several notices.

In October and November, Collins and Blow received letters from both UVA and the tax department informing them of four setoff claims totaling $220, in the amounts of $67.39, $42.61, $78.63 and $31.37. Two of the dollar amounts matched up with the itemized bills from UVA, but two did not. If they wanted to contest the claims, the notices said, they could request a hearing with UVA. Collins did so.

Subsequently, the UVA patient services rep said that as a “one-time courtesy” the health system would release the hold on the $110 from their refund, Collins recounted.

In late May, Collins and Blow received a “patient refund card” worth $31.37 from UVA for their son’s care. But the odyssey continues. The following week, the state tax department informed them it had once again withheld money from their tax refund — $5.79 this time — to satisfy an unpaid UVA debt.

Collins said she planned to call UVA to ask about the refund offset, but she assumes it’s also related to her son’s care nearly 20 years ago.

How much longer will this go on, Collins wonders. Do Collins and Blow still owe money to UVA? If they do owe money, how much do they owe? And why did it take so long for UVA to come looking for it?

Collins said she has asked UVA those questions but hasn’t gotten clear answers. Her frustration is through the roof.

“You know what I think government agencies and state hospitals are good at?” Collins asked. “Obfuscation.”