Around the country, nursing homes trying to protect their residents from the coronavirus eagerly await boxes of masks, eyewear and gowns promised by the federal government. But all too often the packages deliver disappointment — if they arrive at all.

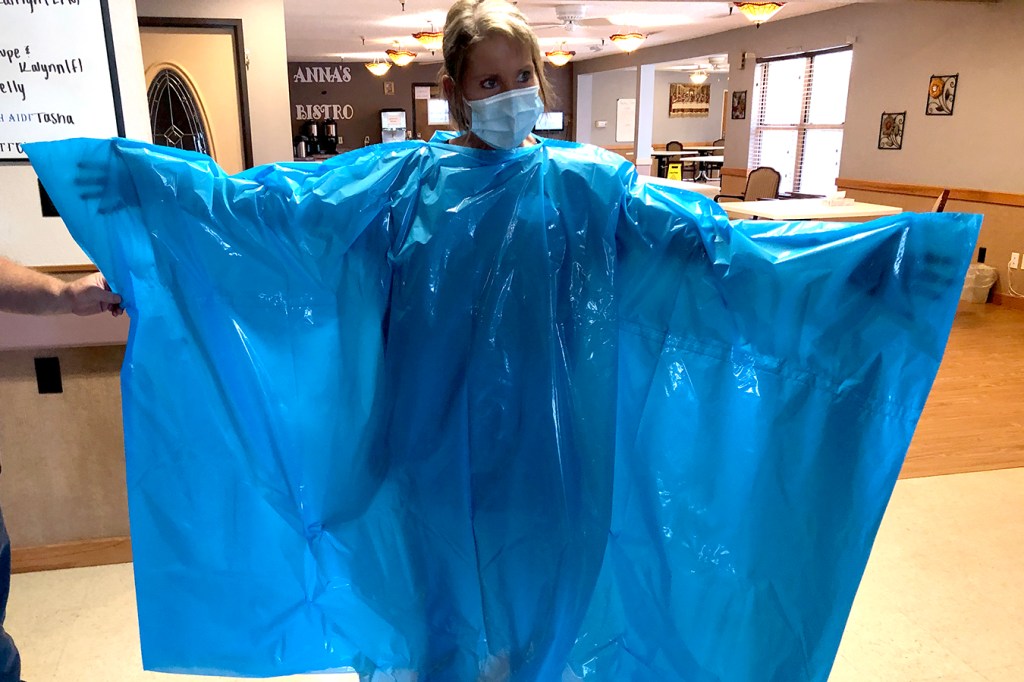

Some contain flimsy surgical masks or cloth face coverings that are explicitly not intended for medical use. Others are missing items or have far less than the full week’s worth of protective equipment the government promised to send. Instead of proper medical gowns, many packages hold large blue plastic ponchos.

“It’s like putting a trash bag on,” said Pamela Black, the administrator of Enterprise Estates Nursing Center in Enterprise, Kansas. “There’s no real place for your hands to come out.”

As nursing homes remain the pandemic’s epicenter, the federal government is failing to ensure they have all the personal protective equipment, or PPE, needed to prevent the spread of the virus, according to interviews with administrators and federal data.

Despite President Donald Trump’s pledge April 30 to “deploy every resource and power that we have” to protect older Americans, a fifth of the nation’s nursing homes — 3,213 out of more than 15,000 — reported during the last two weeks of May that they had less than a week’s supply of masks, gowns, gloves, eye protectors or hand sanitizer, according to federal records. Of those, 946 reported they had at least one confirmed COVID infection since the pandemic began.

“The federal government’s failure to nationalize the supply chain and take control of it contributed to the deaths in nursing homes,” said Scott LaRue, president and CEO of ArchCare, the health care system of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, which operates five nursing homes.

Widespread equipment shortages continue in some places as the virus rages lethally through nursing homes and other long-term care facilities. More than 217,000 short-term patients and long-term residents in nursing homes have contracted COVID-19, and 43,000 have died.

Some homes still have not received the first of two batches of supplies the Federal Emergency Management Agency said it would ship in May. Instead, some got only cloth masks that the Department of Health and Human Services commissioned through a contract with HanesBrands, the apparel company known for its underwear. An HHS webpage says the masks are not intended for caring for contagious patients but can be given to workers for their commutes or to residents when they leave their rooms.

As homes keep scrounging for supplies in a chaotic market with jacked-up prices and continued scarcity, 653 skilled nursing facilities informed the government they had completely run out of one or more types of protective supplies at some point in the last two weeks of May, according to records released last week by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, or CMS.

“The federal government has got to step up,” said Lori Smetanka, executive director of the National Consumer Voice for Quality Long-Term Care, an advocacy group based in Washington, D.C. “We’re now — what? — three months into this pandemic, and these facilities still don’t have enough PPE to protect themselves and their residents?”

A ‘Relentless Commitment’

In April, Trump pledged his administration “will never waver in its relentless commitment to America’s seniors.” But FEMA’s shipments of masks, gloves, gowns and eye protection have had a more modest goal: “to serve as a bridge between other PPE shipments.”

In written comments, FEMA defended the quality of the poncho gowns but said that because of complaints, the contractor was creating a “short instructional video about proper use of the gowns” to share with homes. FEMA officials said that, as of June 4, the agency had shipped packages to 11,287 nursing homes, starting at “the soonest possible date in the COVID-19 global supply chain climate.”

Yet 67 of the Good Samaritan Society’s 147 nursing homes have not received a FEMA shipment, including homes that are fighting the biggest outbreaks in Sioux Falls, South Dakota; Greeley, Colorado; and Omaha, Nebraska, according to Nate Schema, the Evangelical Lutheran society’s vice president of operations. “We have not received a shipment in our six or seven hot spots,” he said.

The supplies that did arrive tended to be in one size only, he said, and “the quality wasn’t quite up to the same level we’ve been receiving” through the society’s affiliation with Sanford Health, a large hospital and physician system.

The society has enough equipment, but small nursing home groups and independent homes are still struggling, particularly with obtaining N95 masks, which filter out tiny particles of the virus and are considered the best way to protect both nursing home employees and residents from transmitting it.

The CMS records show 711 nursing homes reported having run out of N95 masks, and 1,963 said they had less than a week’s worth. But FEMA is not shipping any N95 masks, and nursing homes are having trouble obtaining them from other sources. Instead, it is sending surgical masks, but more than 1,000 homes have less than a week’s supply of those.

Messiah Lifeways at Messiah Village in Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, received a FEMA shipment this week that had face shields and gloves, but only three days’ worth of surgical masks and “very low low-grade quality” gowns that lacked sleeves, said Katie Andreano, a Messiah communications specialist.

Only two of ArchCare’s five nursing homes have received any FEMA shipments even though it is based in New York City, the site of the nation’s biggest outbreak. The equipment for those two homes lasted less than a week. LaRue tried to procure equipment from abroad, but all of the potential suppliers turned out to be fraudulent. He said ArchCare has had to rely on sporadic supplies from the state and city emergency management offices.

“As we sit here today, I’m still not able to get more than a few days’ supply of N95 masks, and I still struggle to a certain extent with gowns,” LaRue said. “That doesn’t make you sleep at night, because you’re not sure when the next delivery comes.”

‘It’s Not Going To Work’

In addition to the supplies, the administration has dedicated $5 billion to nursing homes out of $175 billion in provider relief funds appropriated by Congress. Hospitals are getting much more. Administrators said money doesn’t solve the broken private supply chains, where the availability of PPE is spotty and the equipment is vastly overpriced.

“Too often, the only signs of FEMA’s much-hyped promise of PPE are scattershot delivery with varying amounts of ragtag supplies,” said Katie Smith Sloan, president and CEO of LeadingAge, an association of nonprofit nursing homes and other service agencies for older people.

The cloth masks from HHS have been particularly perplexing to nursing home administrators, given the caveats that accompanied them. The instructions for the masks said they could be washed up to 15 times, according to Sondra Norder, president and CEO of St. Paul Elder Services in Kaukauna, Wisconsin.

“I don’t know how we would possibly track how many times each mask has been washed,” she said. The instructions also said the masks should not be washed with disinfectants, bleach or chemicals, which is how Norder said nursing homes clean their laundry.

Norder said she laundered about 100 masks and they shrank. “The ones that have been washed are tiny, and I certainly wouldn’t want to put something on someone’s face that hasn’t been laundered,” she said. “All my colleagues [at other nursing homes] received the same thing and were also baffled by it, wondering, ‘How are we going to use these?’”

KHN senior correspondent Christina Jewett contributed to this report.