Americans in their 80s and 90s are not the ones amassing the largest medical bills to hold off death, according to a new analysis that challenges a widely held belief about the costs of end-of-life care.

Younger seniors — those with potentially longer expectancies — are.

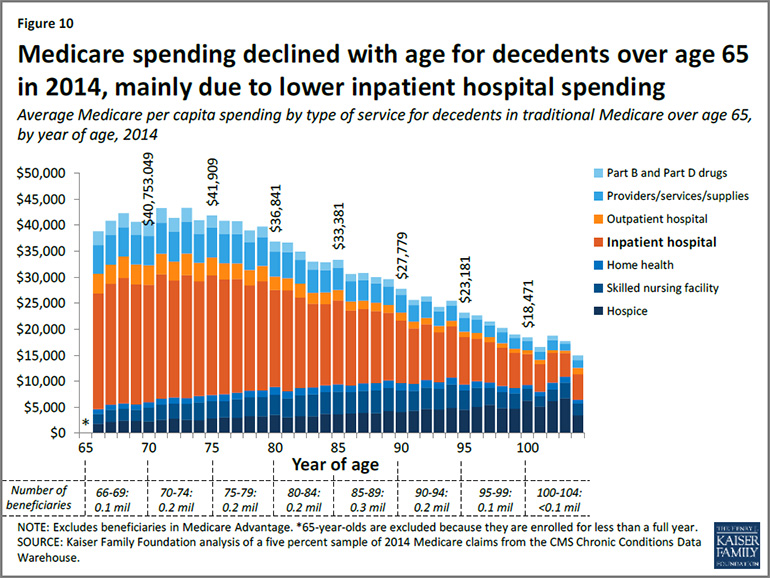

Medicare claims data for 2014 for beneficiaries who died the same year shows that average Medicare spending per person peaked at age 73 — at $43,353, the Kaiser Family Foundation reported Thursday. That compared with $33,381 per person for 85-year-olds and among 90-year-olds, $27,779 per person. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

“This is a pattern we weren’t really expecting to see,” said Juliette Cubanski, the associate director of the program on Medicare policy for the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Kaiser researchers said their findings suggest that providers, patients and their families may favor more costly, lifesaving care for younger seniors, and turn to hospice care when patients are older.

“It kind of goes against the notion that doctors are throwing everything including the kitchen sink at people at the end of life regardless of how old they are,” Cubanski said.

Medicare covered eight of 10 people in the U.S. who died in 2014, establishing it as the largest insurer of medical care provided at the end of life, according to the Kaiser report.

Medicare spent an average of $34,529 on each of them, and most of that money (51 percent) went to inpatient hospital expense. The rest was spent mostly on skilled nursing facilities, home health care and hospice (23 percent) or physicians (13 percent) or medication, 6 percent. Overall, the largest portion, 31 percent, of per capita spending for all beneficiaries goes to inpatient hospital expenses.

The Kaiser team said spending on people who die in a given year represents a small and declining share of traditional Medicare spending —18.6 percent in 2000 but 13.5 percent in 2014.

Overall, the aging baby boomer population is leading to a decrease in the growth of spending on patients’ last years of life. More beneficiaries are younger and healthier, and they are living longer, so their last years of life are cheaper.

Kaiser’s analysis covered only traditional Medicare beneficiaries during the calendar year in which they died and did not include spending in the full 12 months before their deaths. The report also did not include spending on beneficiaries in Medicare Advantage because data was unavailable.