Since the mid-1800s, laughing gas has been used for pain relief, but it’s usually associated with a visit to the dentist.

In the early 20th century, women used it to ease the pain of labor, but its use declined in favor of more potent analgesia. Now, a small band of midwives is helping to revive its use in the U.S.

One hospital in Rhode Island, South County Hospital in North Kingstown, has just added nitrous oxide, the formal name for laughing gas, to its menu of pain relief options for labor.

Amy Marks jumped at the chance to use it because she wanted to avoid an epidural — an injection in the fluid around the spinal cord that blocks feeling below the waist. The day after she gave birth, she sat with her son, Ethan Thomas, snug in the crook of her arm.

“When the contractions started getting pretty intense, I was like, ‘wow, this is pretty bad,'” she said. “So they brought it in and it really took the edge off.”

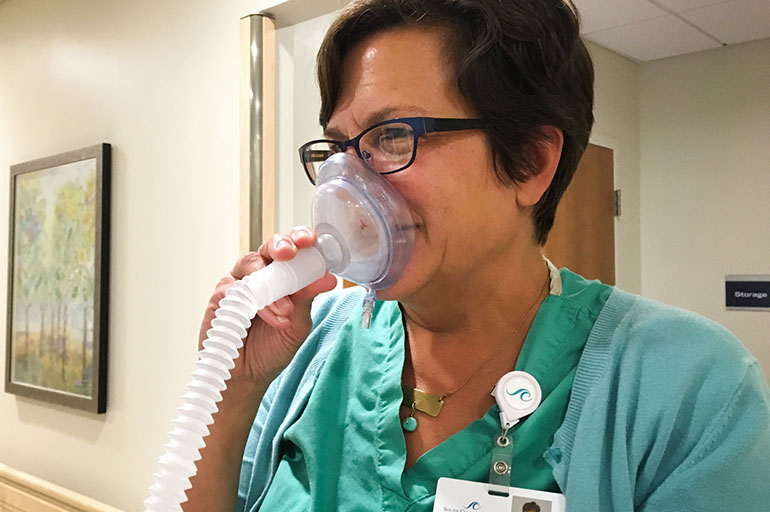

But is taking “the edge off” really enough relief for labor pain? It was for Marks, once she got the hang of breathing in the gas through a face mask, timing it to anticipate the peak pain of a contraction by 15 to 30 seconds.

“You’re going through the contraction, you’re breathing in and out, maybe do five, six breaths, get to the peak of the contraction, and I kind of didn’t really need any more, I could bear the rest of the contraction,” she said. “I was giggly. But only for like 15 to 30 seconds.”

Marks’ midwife Cynthia Voytas said Marks was breathing a mixture of 50 percent nitrous oxide and 50 percent oxygen.

“It gives you this euphoria that helps you sort of forget about the pain for a little bit,” Voytas said.

“Absolutely. That’s exactly what happened,” said Marks.

The laughing gas set up is on a little cart stocked with two gas tanks. It’s mobile, so nurses can just roll it up to the woman’s bedside. There’s a hose with a breathing mask. When she wants a little gas, a woman can just pick up the mask and breathe. Voytas said it gives a mom more control over her pain relief.

Until 2011, only a couple of hospitals in the United States offered nitrous oxide to women in labor. Today, it’s in the hundreds, according to the two main manufacturers of nitrous oxide systems. One of those manufacturers, Porter Instrument, maker of Nitronox, says nearly 300 hospitals and birth centers use the option for pain management.

Dr. Michelle Collins, professor and director of nurse midwifery at the Vanderbilt University School of Nursing, is helping lead the charge to bring back nitrous oxide as one of several options women should be offered for pain relief during childbirth. She sees the effort as being in line with what midwives have always done: advocating for women to have more control of the experience of giving birth.

Baby Ethan Thomas was born without an epidural being administered. (Kristin Espeland Gourlay/RINPR)

Prior to the 1950s, Collins said, nitrous oxide was commonly used in labor. But then in the 1950s and 1960s, doctors started using drugs that could make a person drowsy. Women would go to the hospital, be completely knocked out, and wake up with a baby in their arms. The epidural, which came on the scene in the 1970s, gave women the possibility of a pain-free labor while awake. But it came with trade-offs: epidurals can make it difficult to move around and can prolong the second stage of labor.

Collins said women want more options to be more involved in the birth of their babies.

“Now, women are more informed, and they’re demanding that their voices be heard, which is a really great thing in my book,” she said.

Nitrous oxide has continued to be used regularly in Europe, so there’s data that shows it’s safe, especially in smaller doses. It doesn’t reduce pain, like an epidural. Rather, it induces a sense of euphoria or relaxation.

“For some women, the epidural is going to be their number one choice. For other women, they want to be unmedicated and have nothing and that’s their choice. For other women, nitrous oxide is a viable choice,” she said. “It’s seen somewhat like a menu and for everything that’s safe, it should be on that menu and available to the woman.”

Another leader of this mini-revolution, retired nurse midwife and epidemiologist Judith Rooks, said the gas leaves the body in seconds.

“It does pass the placenta and go into the fetal circulation, but as soon as the baby takes a breath or two, it’s gone,” Rooks said.

The American College of Nurse-Midwives came out with a position paper in 2011, saying it’s important for midwives be aware of nitrous oxide as a good option for women in labor and get trained in how to administer it. Dr. Laura Goetzl, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Temple University’s medical school, researches pain relief in childbirth. She considers nitrous oxide a “safe and reasonable” option and she is encouraging Temple to offer it at its hospital.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists reviewed research and in May 2011, said in a paper that they would like to see more and more rigorous studies on its safety and effectiveness — much of the research is decades old. They also warn that facilities should have a good system for capturing any gas that escapes into the air, so those nearby don’t breathe it in. They note its use in Europe showed, “good safety outcomes for both mother and child.”

Nitrous oxide is less expensive than an epidural by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of dollars. Collins said the disposable breathing apparatus may cost about $25 and the cost of the gas alone, she said, is about 50 cents an hour. An anesthesiologist does not need to administer it — it can be done by a nurse midwife or other trained medical staff. Hospitals are having a hard time figuring out the billing, however, because it’s so new, said Collins.

“The interesting thing is that there’s not a charge code for this particular use of nitrous oxide in labor,” she said. “So places around the country are being very creative in how they’re approaching the charge portion of it.”

One insurer in Rhode Island covers it as it would another painkiller. Some hospitals, says Collins, just swipe a patient’s credit card, or don’t charge at all.

This story is part of a reporting partnership with NPR, local member stations and Kaiser Health News.