Seven years ago, Robert Kerley, who makes his living as a truck driver, was loading drywall when a gust of wind knocked him off the trailer. Kerley fell 14 feet and hurt his back.

For pain, a series of doctors prescribed him a variety of opioids: Vicodin, Percocet and OxyContin.

In less than a year, the 45-year-old from Federal Heights, Colo., said he was hooked. “I spent most of my time high, laying on the couch, not doing nothing, falling asleep everywhere,” he said.

Kerley lost weight. He lost his job. His relationships with his wife and kids suffered. He remembers when he hit rock bottom: One night hanging out in a friend’s basement, he drank three beers, and the alcohol reacted with an opioid.

“I was taking so much morphine that I [experienced] respiratory arrest,” Kerley said. “I stopped breathing.”

An ambulance arrived, and EMTs administered the overdose reversal drug naloxone. Kerley was later hospitalized. As the father of a 12-year-old boy, he knew he needed to turn things around. That’s when he signed up for Kaiser Permanente‘s integrated pain service. (Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

“After seven years of being on narcotics and in a spiral downhill, the only thing that pulled me out of it was going to this class,” he said. “The only thing that pulled me out of it was doing and working the program that they ask you to work.”

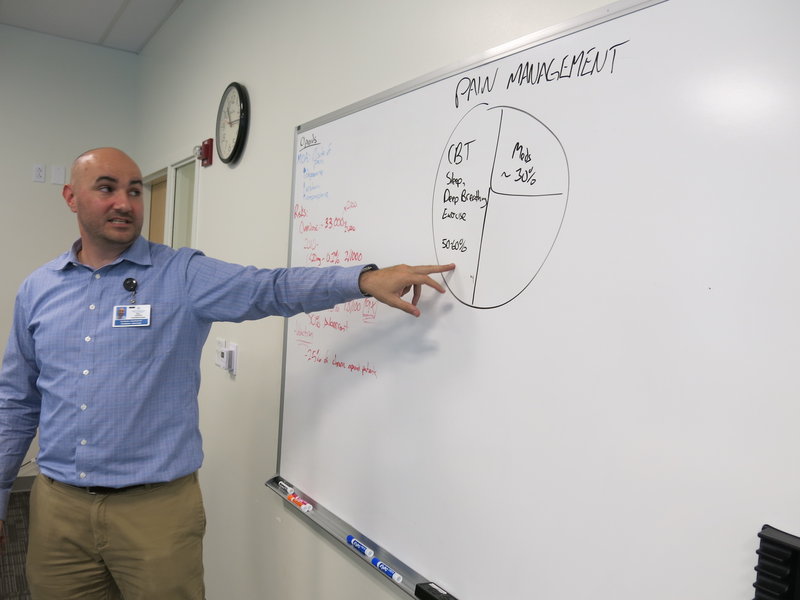

The program he refers to is an eight-week course, available to Kaiser Permanente members in Colorado for $100. It’s designed to educate high-risk opioid patients about pain management. A recent class met at Kaiser’s Rock Creek medical offices in Lafayette, Colo., a town east of Boulder. Will Gersch, a clinical pharmacy specialist, taught several patients learning to battle addiction the science behind prescription drugs.

“So, basically the overarching message here is the higher the dose of the opioids, the higher the risk,” he told the group, as he jotted numbers on a whiteboard. “If you’re over these two doses, that’s a risk factor.”

Amanda Bye, a clinical psychologist, works as part of an integrated medical team to treat people with chronic pain. (John Daley/Colorado Public Radio)

Upstairs, Gersch’s colleague Amanda Bye, a clinical psychologist, highlighted a key element of the program: It’s integrated. For patient care, there’s a doctor, a clinical pharmacist, two mental health therapists, a physical therapist and a nurse — all on one floor. Patients can meet with this team, either all at once or in groups, but they do not have to deal with a series of referrals and appointments in different facilities. A spokesperson for Kaiser Permanente said researchers tracked more than 80 patients over the course of a year and found the group’s emergency room visits decreased 25 percent. Inpatient admissions dropped 40 percent, and patients’ opioid use went way down.

“We brought in all these specialists. We all know the up-to-date research of what’s most effective in helping to manage pain,” Bye said. “And that’s how the program got started.”

Bye said the team helps patients use alternatives like exercise, meditation, acupuncture and mindfulness. Some patients, though, do need to go to the chemical dependency unit for medication-assisted treatment for their opioid addiction. Benjamin Miller is an expert on integrated care with the national foundation Well Being Trust. Kaiser is on the right track, he said.

“The future of health care is integrated and, unfortunately, our history is very fragmented, and we’re just now catching up to developing a system of care that meets the needs of people,” he said.

Similar projects in California showed a reduction in the number of prescriptions and pills per patient, said Dr. Kelly Pfeifer, director of high-value care at the California Health Care Foundation. Her group released case studies of three programs similar to Kaiser’s Colorado program. (Kaiser Health News produces California Healthline, an editorially independent publication of the California Health Care Foundation.)

“We’ve seen great success with these models that are integrating complementary therapy, physical therapy, behavioral health and medical care,” Pfeifer said. A key strategy is to gradually decrease the amount of opioids a patient takes, rather than cut them off before they’re ready. “It works so much better when the patients have access to these complementary therapies,” she said. “And it works even better when those complementary therapies are part of an integrated team.”

But it can be difficult to implement universally. One challenge is scale: Big systems like Kaiser Permanente have ample resources and enough patients to make the effort work. Another issue is payment. Some insurers won’t pay for some alternative treatments; others have separate payment streams for different kinds of care.

“Frequently, behavioral health and medical health are paid for by entirely different systems,” Pfeifer said.

Robert Kerley is recovering from an opioid addiction with help from Kaiser Permanente’s pain management program in Colorado. (John Daley/Colorado Public Radio)

The need for programs like Kaiser’s is urgent. In 2016, a record 912 people died from an overdose in Colorado, according to data recently released by the state health department. Of those, 300 people died from an opioid overdose. Opioid use often leads to an addiction to heroin, which claimed another 228 lives last year in the state. Those two causes together now rival the number of deaths from car accidents in the state.

Colorado faces a severe shortage of treatment options. Making matters worse, the state’s largest substance abuse treatment provider, Arapahoe House, decided to close as of Jan. 2.

Kaiser’s integrated pain service has given some patients a second chance.

Robert Kerley, now a veteran of the program, recently shared his story with other patients. “I got my life back. I can sleep. I can eat. I can enjoy things,” Kerley told them.

To cope with pain, Kerley starts his morning with stretching and a version of tai chi that he calls “my chi.” He practices deep breathing. His advice to others suffering from pain or addiction?

“Do whatever it takes to walk away from it, like no matter what,” Kerley said. “Trust me, it gets better. It gets 100 percent better than where you’re at right now.”

Better for Kerley means his relationships with his family have improved. And he’s back at work, once again able to make a living as a truck driver.

This story is part of a reporting partnership with NPR, Colorado Public Radio and Kaiser Health News.