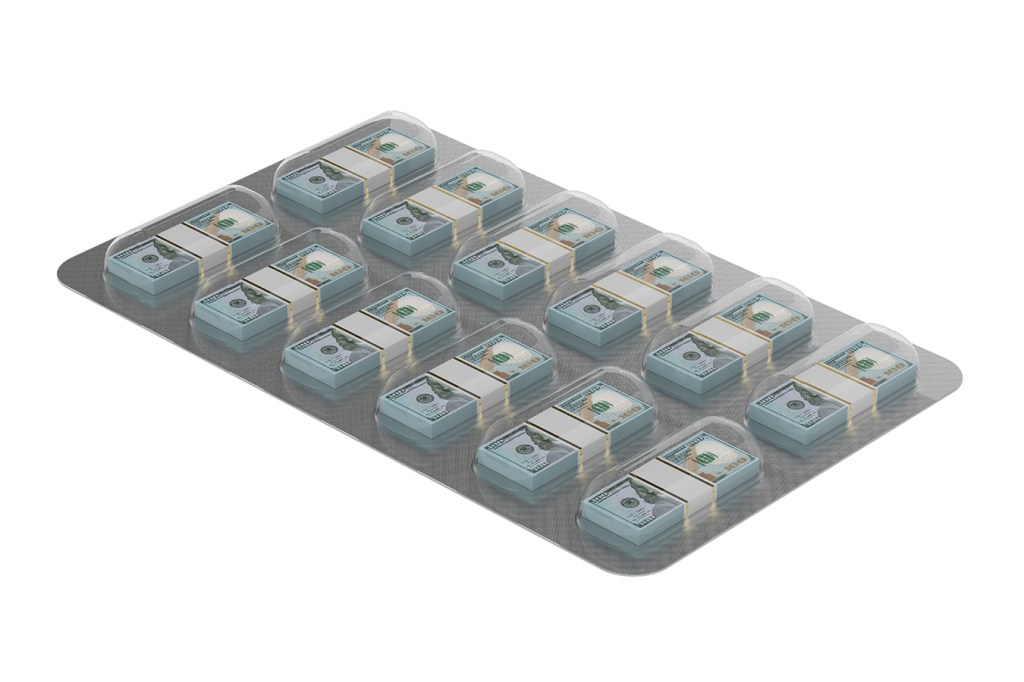

Prescription drug prices were soaring. Angry policymakers swore they’d take action. Pharma giant Merck responded by promising to address the problem voluntarily, vowing to keep price increases under the overall rate of inflation.

“We believe these moderate increases are a responsible approach, which will help to contain costs,” the Merck CEO said at the annual shareholders meeting.

That assurance wasn’t made last week, when multiple drug companies offered similar pledges amid similar criticism. It was nearly three decades ago, in 1990.

Promises by the pharmaceutical industry to contain prices are a familiar — and fleeting — phenomenon, say analysts who have watched the unstoppable rise in drug costs over the years.

History’s lesson, they say, is that price-restraint vows last only as long as it is politically necessary for companies to make them. Recent pharma pledges are unlikely to be any different, they predict.

“These things are always very temporary,” said Paul Ginsburg, director of the University of Southern California-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy. “I don’t think anyone considers this significant.”

Last week, Swiss drugmaker Novartis said it would not raise prices on U.S. products between now and the end of the year. Pfizer, Merck, Sanofi and Roche have all made similar announcements in the wake of repeated criticism from policymakers, especially President Donald Trump.

The current assurances come as the administration floats proposals that could contain costs at the margins, such as promoting competition from generic drugs or changing Medicare drug-purchase policies, some analysts believe.

“The president is using the bully pulpit to make some change, and that is certainly one aspect of using the power of the presidency,” said Dan Mendelson, who founded consultancy Avalere Health and oversaw the health division at the Office of Management and Budget under President Bill Clinton. “If you make changes to regulation and law, those are certainly more durable … over the long term.”

One big wave of pharma price vows came in the early 1990s. Expensive new drugs such as antidepressants and statins to lower cholesterol were quickly driving up costs — although overall prices were far lower than they are now.

Ethicists and consumer advocates were outraged that lifesaving AZT, which counteracted the HIV virus, cost about $8,000 a year when it launched in the late 1980s. These days the cost of some medicines exceeds $1 million a year.

Criticism from policymakers back then might also sound familiar.

“There is no question that we face a growing crisis in the United States due to rising prescription drug prices,” Sen. David Pryor, an Arkansas Democrat who was chairman of the Aging Committee, said in 1990.

In response came a cascade of public promises to limit drug price increases to no more than the rate of inflation.

Merck was one of the first, taking what became known as “the Rahway pledge,” referring to the New Jersey location of its headquarters. Pfizer made a similar promise in 1992, saying it would limit increases to 4 percent or less.

“Pfizer is mindful of the needs of the broader public,” Pfizer chief executive William Steere Jr. told industry analysts in a presidential election year in which both Democrats and Republicans were discussing health care reform.

Bristol-Myers Squibb and Glaxo also said they would keep price increases below inflation, according to a 1992 Newsday story that quoted an analyst referring to “pharmapolitically correct” price promises.

Just two years later, Pryor said many manufacturers were raising prices far faster than the inflation rate. He found that prices for especially profitable and high-volume drugs went up sharply. That echoes today’s criticism of the industry.

Merck recently announced it would cut prices by 10 percent on half a dozen drugs, a seemingly significant concession. But those medicines together account for less than 0.1 percent of the company’s sales, calculated Umer Raffat, an analyst at Evercore ISI. That suggests the move was “just optics” rather than substance, Raffat said in a note to clients.

“We commit to not increase the average net price across our portfolio of products by more than inflation annually,” Merck said last week.

Prescription drug prices have continued to soar in recent years, far outpacing the rate of overall inflation, according to the AARP Public Policy Institute.

“Every now and then senior company executives decide that there is so much anger and pressure, and they will show they are good citizens” by promising to restrain prices, said Donald Light, health policy professor at Rowan University’s School of Osteopathic Medicine in New Jersey. “But it only happens for a year or two.”

On the other hand, industry watchers say, the political and economic environment has shifted since the 1990s. Drug prices are higher than ever. Because of high-deductible insurance plans and other cost-shifting, “consumers are responsible for a much larger burden” in paying for drugs, Mendelson said.

That’s why some are not ruling out at least peripheral regulation and perhaps new laws to address pharma prices.

The administration’s drug “blueprint” has proposed lowering Medicare reimbursement on hospital- and doctor-administrated drugs. Last week, the administration proposed altering a rule on drug rebates used when pharmacy benefit managers negotiate prices with insurers and drug companies.

Avalere President Matt Brow said there is a political reason to make something happen before the November midterm elections.

“I think this administration is willing to take action that most administrations in our memory haven’t been willing to do,” Brow said.

KFF Health News' coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.