Recently, a Wall Street Journal expose and a New York Times column by Princeton economist Uwe Reinhardt detailed how vast health care resources are steered by the American Medical Association’s Relative Value Scale Update Committee — or RUC, a secretive, 29 person, specialist-dominated panel. Since 1991, the RUC has been the main, if unofficial, adviser on Medicare physician reimbursement how specific procedures should be valued – to what is now called the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Many Medicaid and commercial health plans follow Medicare’s lead on payment, so the RUC’s influence is sweeping.

Not surprisingly, the Committee’s payment recommendations have consistently favored specialists at the expense of primary care physicians. More striking, however, is CMS’ rubber stamping of about 90 percent of their suggestions, even though, in their last three service reviews, the RUC urged payment increases six times more often than decreases.

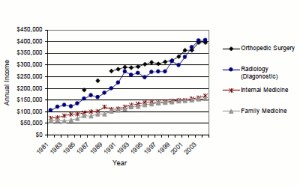

This arrangement has played out well for specialists, but the health system consequences have been catastrophic. One significant result has been a primary care shortage. Specialists now earn, on average, $135,000 a year and $3.5 million over the course of their careers more than their primary care colleagues. The income disparity has driven all but the most idealistic medical students away from primary care.

Figure 1. Comparison of annual income (median compensation) by physician subspecialty. Source: Phillips RL Jr, et al.; Robert Graham Center. Specialty and geographic distribution of the physician workforce: what influences medical student and resident choices? March 2009. Accessed January 4, 2010.

Most health care professionals acknowledge the compelling evidence that primary care reduces cost while improving quality and are chagrined by its devaluation. Susan Dentzer, editor-in-chief of Health Affairs, calls American primary care “horribly broken.” A 2008 Physicians Foundation survey found an overwhelming 78 percent of doctors in all specialties believe the U.S. has a primary care shortage. During the reform debate, advocates and critics alike wondered whether universal coverage was practical in a system in which most primary care doctors’ capacity was already saturated.

But there is a more insidious and destructive issue at hand. The perverse incentives that are embedded in fee-for-service physician payments influence care decisions and are a principal driver of the health system’s immense excesses. Encouraged by the RUC, sometimes unnecessary specialty procedures may appear more valuable and appropriate than primary care services. The system pays more for invasive approaches, so conservative treatment choices that are lower cost and lower risk to the patient may be passed over, especially near the end of life. The resulting waste, half or more of all health care dollars, has fueled a cost explosion that has led the industry and the larger economy to the brink of instability.

Even so, although the health law began a transition away from fee-for-service reimbursement, it gave short shrift to remedying the shortcomings in primary care reimbursement, offering a mere 10 percent boost, and only if office visits account for at least 60 percent of overall Medicare charges. One can speculate why primary care was mostly ignored. But the wealthier specialists, and the drug and device firms that support them, apparently had more influence over policy.

In the absence of meaningful policy-based payment reforms, the RUC’s specialty bias continues to hold sway over payment policy. Dr. Reinhardt calls for a broader, more balanced, independent panel. We agree.

Given the recent attention to the issue, it is possible — but unlikely — that CMS will move toward that approach. The professionals and organizations that benefit from the current structure will fight to maintain the status quo.

So we propose a radical action. Quit the RUC.

America’s primary care medical societies should loudly and visibly leave, while presenting evidence that the process has been unfair to their physicians and, worse, to American patients and purchasers. Primary care physicians have tried to change the process, but to no avail. Leaving would de-legitimize the RUC, paving the way for a new, more balanced process to supplant it.

There are times when hopeful discussions and appeasement simply enable the continuation of an unhealthy situation. Abandoning and replacing the RUC would be an important first step toward re-stabilizing primary care, health care and the larger economy.

Brian Klepper, PhD and David C Kibbe, MD MBA write together on health care issues. The views stated are their own. Although David Kibbe is a senior adviser to the American Academy of Family Physicians, this commentary is not associated with the AAFP.