In the end, literally, the candidates returned to health care.

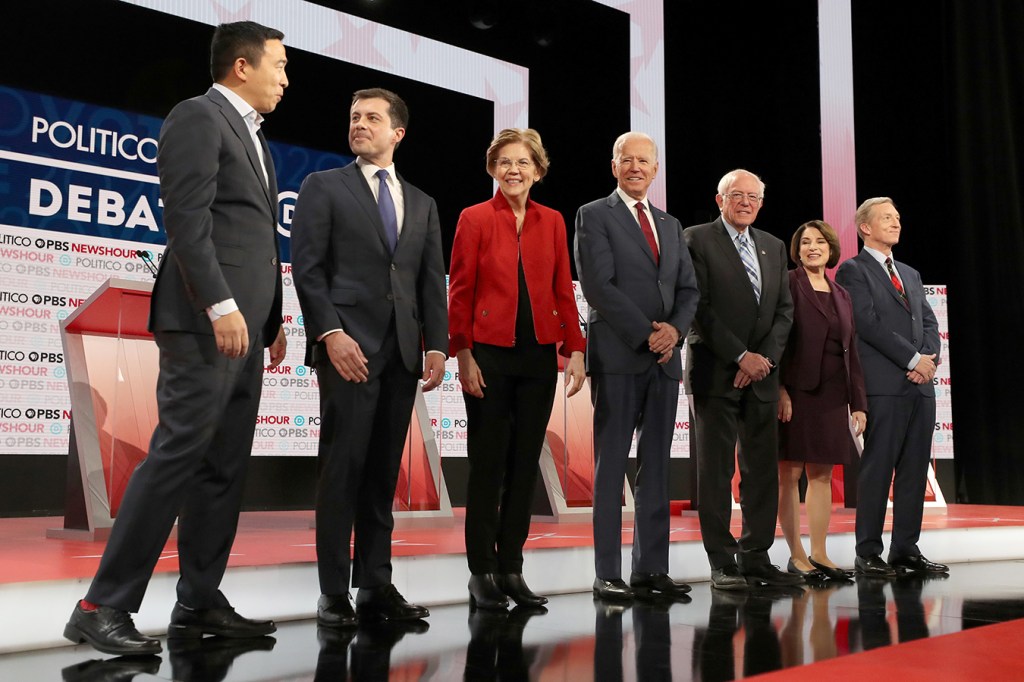

The sixth Democratic presidential debate on Thursday is likely to be best remembered for its sharp exchanges over campaign finance and a glistening fundraiser in a Napa Valley wine cave. But just before their closing statements, after lengthy discussions of impeachment, climate change and human rights in China, the seven candidates who qualified for the last debate of 2019 talked about the practicality of sweeping health care reform — specifically, “Medicare for All.”

In light of the Obama administration’s challenges passing the Affordable Care Act nearly a decade ago, former Vice President Joe Biden was asked about the likelihood of being able to replace the nation’s existing health care with a single-payer system.

“I don’t think it is realistic,” he replied.

Biden noted that Americans are already paying taxes for a relatively small portion of the population to be covered by Medicare, suggesting taxes would skyrocket under a single-payer system.

Yes, Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont replied, taxes would go up under his Medicare for All plan. But premiums, deductibles and out-of-pocket expenses would disappear, he said, and there would be an annual cap on prescription drug costs.

“The day has got to come, and I will bring that day about, when we finally say to the drug companies and the insurance companies, the function of health care is to provide it for all people in an effective way,” Sanders said, “not to make profits for the drug companies and the insurance companies.”

Sen. Amy Klobuchar of Minnesota, who, like Biden, has proposed adding a public option to the existing system, took a folksier approach to criticizing Medicare for All.

“If you want to cross a river over some troubled waters, you build a bridge,” she said. “You don’t blow one up.”

It was an encore of an argument over health care reform that has become familiar to anyone who watched, well, any of the previous five debates.

But with six Democratic debates to go in the primary season, the candidates also waded into topics that focused more on care: the startling racial disparities in maternal mortality rates and the treatment of those with disabilities.

Andrew Yang, a businessman who is mostly running on his proposal to institute a universal basic income of $1,000 a month, noted that black women are 320% more likely to die in childbirth.

That disparity has prompted calls to extend Medicaid coverage, ensuring many new moms are not kicked off their health care shortly after giving birth.

And speaking as the parent of a child with special needs, Yang noted his universal basic income plan could help shift more of the responsibility for caring for those with disabilities away from cash-strapped local governments.

“We’re going to take this burden off of the communities and off of the schools who do not have the resources to support kids like my son, and make it a federal priority, not a local one, so they’re not robbing Peter to pay Paul,” he said.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts, who taught children with special needs, vowed to fully fund the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, a law passed in 1975 that was intended to provide free, specialized education to those with disabilities.

She added that she would also focus on supporting those with disabilities in housing and the workplace.

“You’ve got to go at it at every part of what we do,” Warren said. “Because as a nation, this is truly a measure of who we are.”

The seventh debate is scheduled for Jan. 14, with three more to follow in February and another two yet to be announced.