Of all the promises President Donald Trump made for the early part of his term, controlling stinging drug prices might have seemed the easiest to achieve.

An angry public overwhelmingly wants change in an easily vilified industry. Big pharma’s recent publicity nightmare included thousand-percent price increases and a smirking CEO who said, “I liken myself to the robber barons.” Even powerful members of Congress from both parties have said that drug prices are too high.

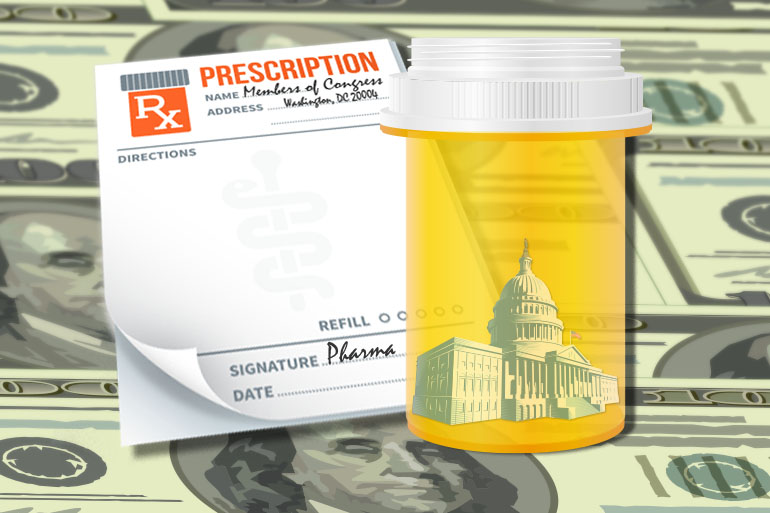

But any momentum to address prescription drug costs — a problem that a large number of Americans now believe government should solve — has been lost amid rancorous debates over replacing Obamacare and stalled by roadblocks erected via lobbying and industry cash.

“There is a very aggressive lobby that is finding any and all means to thwart any reform to a system that has produced very lucrative profits,” said Ameet Sarpatwari, an epidemiologist and lawyer at Harvard Medical School who follows drug legislation. “Everything that’s coming out is being hit and hit hard — even stuff that’s commonsensical.”

Those in Congress concerned with health policy have spent much of the year advancing proposals to overhaul the Affordable Care Act, none of which would affect pharmaceutical pricing. The latest Republican proposal, by Senators Lindsey Graham of South Carolina and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, is no different.

Meanwhile, more than two dozen bills aimed at curbing drug costs have been introduced in this or the previous Congress, according to the Drug Pricing Lab, a Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center program that has catalogued ideas for reducing prices. Many have bipartisan support.

Proposals include importation from other developed countries, where regulations keep prices down; allowing government to negotiate the price of Medicare-covered drugs; speeding approval of cheaper generics; requiring notification before raising drug prices; and restricting consumer drug ads.

(Story continues below.) Other ideas that haven’t made it to legislation include banning patents for pills that simply copy or repackage existing medicines; and adjusting prices according to a drug’s effectiveness.

“There’s clearly no single solution out there that will solve this rapidly rising spending,” said Dr. Peter Bach, who leads the lab. But, he added, “there’s not a lot of fundamental disagreement about the direction this needs to move.”

Trump drew new attention to the issue last month by tweeting that Merck’s chief executive, Kenneth Frazier, “will have more time to LOWER RIPOFF DRUG PRICES!” after Frazier quit the president’s manufacturing council to protest his remarks about white supremacists in Charlottesville, Va.

Those comments matched Trump’s characterization earlier this year of drug companies as “getting away with murder.” That same January day, a dozen Republican senators, including Ted Cruz of Texas, John McCain of Arizona and Mike Lee of Utah, voted for the old liberal idea of letting Americans buy less-expensive drugs from Canada.

The measure was attached to a budget resolution and wouldn’t, by itself, have allowed importation. It failed 52 to 46 after 13 Democrats voted against it, with some citing safety concerns about foreign-sourced medicine — an idea promoted by American drugmakers.

Even so, the vote prompted speculation that a pharma price deal might be within reach.

Sen. Lee is one of the Republicans who favor importation as a way to increase competition. “When we’re talking about garden-variety, generic drugs that can be easily imported from another country that has regulatory procedures that make them safe?” he said in an interview. “I don’t see why not.”

In response to the new threats, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, already one of Washington’s biggest-spending trade groups, increased member dues by half last year to prepare for battle.

The pharmaceutical and health products industries spent $145 million on lobbying for the first half of 2017, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics.

Drug manufacturers gave $4.5 million to congressional campaigns in that period, including six-figure donations to House Speaker Paul Ryan; Rep. Greg Walden, head of the House Energy and Commerce Committee; and Sen. Orrin Hatch, head of the Senate Finance Committee, according to a Kaiser Health News analysis.

PhRMA’s “Go Boldly” campaign, showing heroic researchers seeking cures, has spent $28 million so far this year on six ads shown on about 4,600 national TV channels, according to iSpot.tv, an ad tracker.

The industry hired former FBI director Louis Freeh to study the impact of importation. He concluded that it would “leave the safety of the U.S. prescription drug supply vulnerable to criminals seeking to harm patients.” Import proponents argue the Food and Drug Administration could easily ensure safety by licensing and inspecting Canadian suppliers.

Drugmakers say that high prices reflect heavy investment in innovation and drug development. They reject the notion that the industry wields too much influence in Washington.

“These are important issues with significant ramifications,” Holly Campbell, a PhRMA spokeswoman, said. “So we will continue to be engaged with the administration to advance solutions that improve the marketplace and make it more responsive to the needs of patients.”

The top 10 publicly traded U.S. drug companies made $67.8 billion last year, after taxes, regulatory filings show.

Efforts to restrain prices have made little progress in the executive branch, either.

The White House has long been expected to issue an executive order on drug costs. But leaked documents show that deliberations have focused on things the industry wants, such as extending overseas patents and changing a drug-discount program for hospitals, and not so much on lowering prices.

Gerard Anderson, a health policy professor at Johns Hopkins University, said Trump’s draft order “did not talk at all about branded drugs or about specialty drugs,” including for rheumatoid arthritis and cancer, that have seen especially steep price increases. “If that represents the administration’s thinking, then my guess is there is not much effort.”

Trump’s ongoing feud with congressional Republicans, especially Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, means “you’re not going to get any strong direction or leadership out of the White House” on drug prices, said Vishnu Lekraj, who follows pharma stocks for Morningstar, an investment research firm.

Trump isn’t the only one in his administration criticizing drug companies. Scott Gottlieb, the FDA commissioner, has accused the industry of “gaming” the system to delay the appearance of cheap generics after patents expire. He has pledged to speed applications for generics when there is little competition as part of a “drug competition action plan” while opposing stronger measures like allowing importation.

But promoting generics is “reasonably small potatoes” compared with the money that could be saved by putting direct pressure on brand-drug prices, Anderson said. Gottlieb has served on the boards of several pharmaceutical companies and reaped large consulting and speaking fees from the industry.

Yet even small potatoes might be a long shot — despite widespread agreement that change is needed.

“It is sort of remarkable to see just how far the system can bend before meaningful reform is taken,” said Sarpatwari of Harvard. “If there ever was a time to strike while it’s hot, it’s now.”

Elizabeth Lucas and Sydney Lupkin contributed to this report.

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.