The federal government, which spends billions of dollars each year covering unintended pregnancies, is encouraging states to adopt policies that might boost the number of Medicaid enrollees who use long-acting, reversible contraceptives.

LARCs, as they are known, “possess a number of advantages,” Vikki Wachino, deputy administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, wrote to state programs in a recent bulletin. “They are cost-effective, have high efficacy and continuation rates, require minimal maintenance, and are rated highest in patient satisfaction.”

And, Wachino stressed, “more can be done to increase this form of contraception.”

The federal push reflects the continuing concern over the nation’s rate of unintended pregnancies, which is one of the highest among developed countries. The costs are significant not only for the families involved but also for the federal and state governments. In 2010, the latest year for which data are available, the federal government spent $14.6 billion and states another $6.4 billion on unplanned pregnancies. (Southern states were especially affected. In Mississippi, public programs covered 82 percent of such pregnancies.)

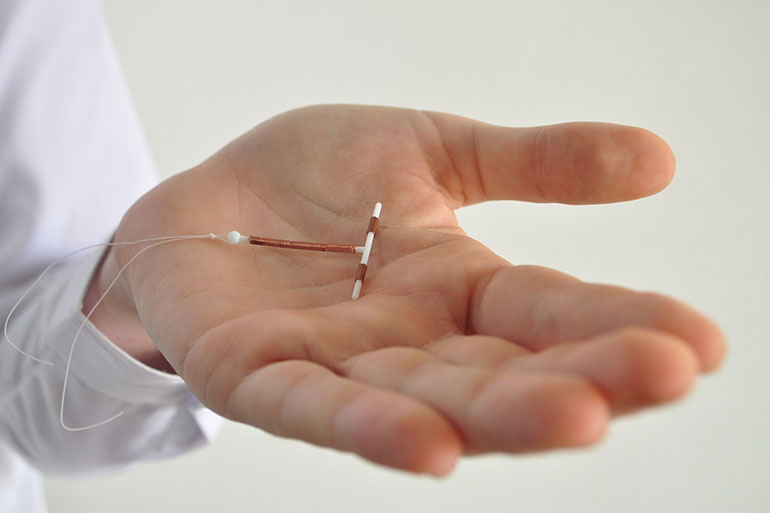

LARCs are considered a key way to help reduce all of those numbers. They include intrauterine devices and under-the-skin hormonal implants that, once in place, provide nearly complete protection against pregnancy for three to 10 years. In contrast, birth control pills are about 90 percent effective and must be taken daily.

Under Medicaid, the state/federal health program for low-income people, states must cover family planning services for women and men without charge. Although they have considerable latitude in determining which services, they’ve generally included most methods of birth control, said Adam Sonfield, a senior public policy associate at the Guttmacher Institute, a research and advocacy organization that focuses on reproductive and sexual health.

Yet overall adoption of long-acting contraceptives has been slow in state Medicaid programs. In 2012, about 11 percent of low-income beneficiaries used a LARC, similar to the percentage of U.S. women overall.

Access in programs can be hampered by policies related to how LARCs are paid for and how services are provided, the CMS bulletin noted. It highlighted how some states are making changes to expand LARC use.

For example, it often is more efficient for a woman who has just delivered a baby to have an IUD inserted while she’s still at the hospital rather than wait until a postpartum visit several weeks later. But providers generally receive a bundled payment for labor and delivery services under Medicaid — and that doesn’t include IUD insertion. A dozen states — Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Illinois, Iowa, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, New Mexico, New York and South Carolina, according to the CMS bulletin — have implemented policies that now reimburse providers separately for inserting an IUD or hormonal implant right after a woman gives birth.

Another hurdle is the high up-front cost of long-acting contraceptives. This can be addressed by increasing payment rates to doctors as an incentive for them buying and stocking the devices, the bulletin noted.

Some state programs require that Medicaid participants first try a different contraceptive method before moving to a LARC, a practice referred to as step therapy. Or they require a plan’s prior authorization, which can delay or even block women from getting that method. Both minimize use.

South Carolina, which in 2011 had the 12th highest teen pregnancy rate in the country, became the first Medicaid program to change its policy to reimburse providers for placement of LARCs immediately after delivery. The state now encourages the use of LARCs in outpatient settings by allowing the devices to be ordered by a physician but billed directly to Medicaid. In addition, it has eliminated prior authorization and step therapy as requirements.

The Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank, published a study last week calling for the increased use of LARCs for Medicaid enrollees both right after delivery as well as following abortion. It’s just one of a growing number of advocates, starting two years ago with the Association of State and Territorial Health Officials and continuing with the National Institute for Children’s Health Quality.

“The research is clear, LARC is the most effective and, over time, the least expensive reversible contraceptive method,” the nonprofits NICHQ and the the National Academy for State Health Policy stated in an issues brief last month. “Unplanned pregnancies are both medically difficult, with higher rates of preterm birth and low-birth weight babies, and incredibly costly. Wider adoption of LARC is a significant opportunity for states to reduce unnecessary expenditures in Medicaid programs.”

A recently published rule for managed care organizations that run many Medicaid programs also addressed LARCs. It said states must offer enrollees a choice of contraceptive methods and can’t require prior authorization or step therapy, said Mara Gandal-Powers, counsel for health and reproductive rights at the National Women’s Law Center.

“The language reinforces women’s access to the birth control method of their choice,” she said.

This story has been updated to add a link to the study by the NICHQ and the National Academy for State Health Policy.

Please contact Kaiser Health News to send comments or ideas for future topics for the Insuring Your Health column.