When Kea Turner’s 74-year-old grandmother checked into Virginia’s Sentara Virginia Beach General Hospital with advanced lung cancer, she landed in the oncology unit where every patient was monitored by a bed alarm.

“Even if she would slightly roll over, it would go off,” Turner said. Small movements ― such as reaching for a tissue ― would set off the alarm, as well. The beeping would go on for up to 10 minutes, Turner said, until a nurse arrived to shut it off.

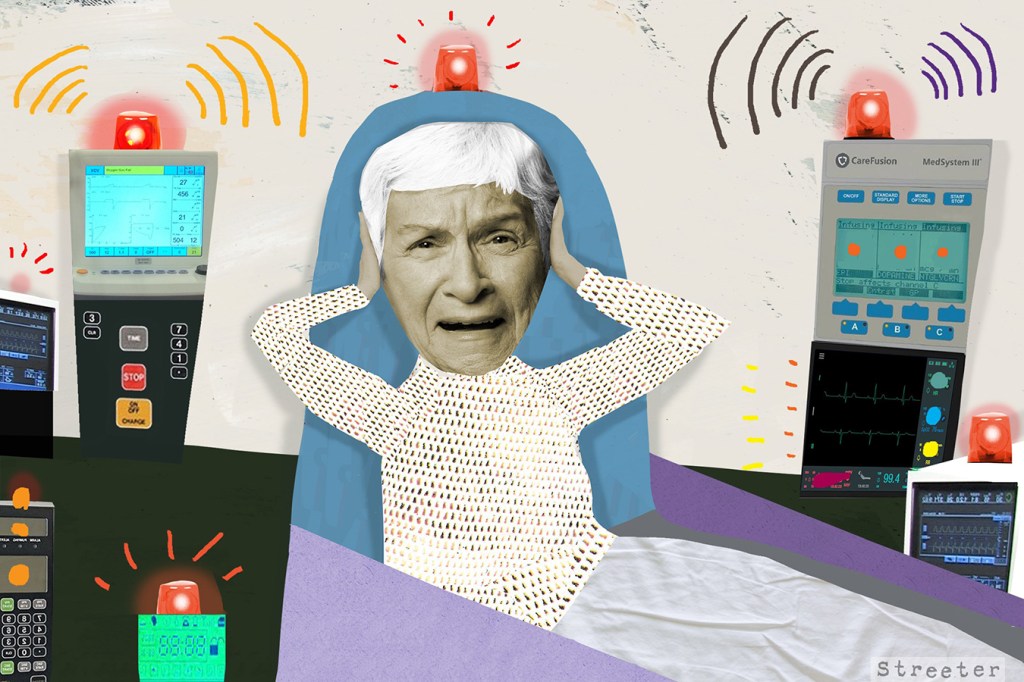

Tens of thousands of alarms shriek, beep and buzz every day in every U.S. hospital. All sound urgent, but few require immediate attention or get it.

Intended to keep patients safe alerting nurses to potential problems, they also create a riot of disturbances for patients trying to heal and get some rest.

Nearly every machine in a hospital is now outfitted with an alarm ― infusion pumps, ventilators, bedside monitors tracking blood pressure, heart activity and a drop in oxygen in the blood. Even beds are alarmed to detect movement that might portend a fall. The glut of noise means that the medical staff is less likely to respond.

Alarms have ranked as one of the top 10 health technological hazards every year since 2007, according to the research firm ECRI Institute. That could mean staffs were too swamped with alarms to notice a patient in distress, or that the alarms were misconfigured. The Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, warned the nation about the “frequent and persistent” problem of alarm safety in 2013. It now requires hospitals to create formal processes to tackle alarm system safety, but there is no national data on whether progress has been made in reducing the prevalence of false and unnecessary alarms.

The commission has estimated that of the thousands of alarms going off throughout a hospital every day, an estimated 85% to 99% do not require clinical intervention. Staff, facing widespread “alarm fatigue,” can miss critical alerts, leading to patient deaths. Patients may get anxious about fluctuations in heart rate or blood pressure that are perfectly normal, the commission said.

And bed alarms, a recent arrival, can lead to immobility and dangerous loss of muscle mass when patients are terrified that any movement will set off the bleeps.

An ‘Epidemic Of Immobility’

In the past 30 years, the number of medical devices that generate alarms has risen from about 10 to nearly 40, said Priyanka Shah, a senior project engineer at ECRI Institute. A breathing ventilator alone can emit 30 to 40 different noises, she said.

In addition to triggering bed alarms, patients who move in bed may set off false alarms from pulse oximeters, which measure the oxygen in a patient’s blood, or carbon dioxide monitors, which measure the level of the gas in someone’s breath, she said.

Shah said she has seen hospitals reduce unneeded alarms, but doing so is “a constant work in progress.”

‘Cry Wolf Phenomenon’

Maria Cvach, an alarm expert and director of policy management and integration for Johns Hopkins Health System, found that on one step-down unit (a level below intensive care) in the hospital in 2006, an average of 350 alarms went off per patient per day, from the cardiac monitor alone.

She said no international standard exists for what these alarms sound like, so they vary by manufacturer and device. “It’s really impossible for the staff to identify by sound everything that they hear,” she said.

The flood of alarms creates a “cry wolf phenomenon,” Cvach said. The alarms are “constantly calling for help. The staff look at them. They say that’s just a false alarm ― they may ignore the real alarm.”

Bed alarms, for example, are meant to summon nurses so they can supervise patients to walk safely. But research has shown that the use of alarms doesn’t prevent falls. Nursing staffs are often stretched thin and don’t reach the bedside before a patient hits the ground.

Meanwhile, patients may feel immobilized at a time when even a few hundred steps per day could significantly improve their recovery. Immobility in the hospital can create other problems for patients, leaving them with often irreversible functional decline, research has shown.

Bed alarms have proliferated since 2008, when the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services declared hospital falls should “never” happen and stopped paying for injuries related to those falls. After that policy change, the odds of nurses using a bed alarm increased 2.3 times, according to a study led by Dr. Ronald Shorr, director of the Geriatric Research, Education and Clinical Center at the Malcom Randall Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Gainesville, Fla. The alarms have become a standard feature in new hospital beds.

But Shorr noted that, in contrast, bed alarms are being removed from other settings: In 2017, CMS began discouraging their widespread use in nursing homes, arguing that audible bed or chair alarms may be considered a “restraint” if the resident “is afraid to move to avoid setting off the alarm.”

Barbara King, an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison School of Nursing, who has interviewed patients about their experience with bed alarms, said patients find them “very restrictive.”

“They’re loud. For some patients, it’s frightening. They don’t know where it’s coming from. It’s a source of irritation,” she said. “For some patients, they won’t move.”

Seeking Solutions

Hospitals have turned to “clinical alarm management,” bringing in consultants to figure out how many devices have alarms, which go off most frequently and which are the most important for nurses to respond to. Hospitals are also installing sophisticated software to analyze and prioritize the constant stream of alerts before relaying the information to staff members.

The U.S. market size for the management of clinical bed alarms, in hospitals and other settings, has grown from $21.4 million in 2016 to $37.4 million in 2018, according to an analysis by MarketsandMarkets. The firm projects the market size will quadruple to $155.5 million by 2023.

For ventilators, it estimates the U.S. market for clinical alarm management will quadruple from $19.9 million in 2018 to $80.2 million by 2023.

In Virginia, Kea Turner’s grandmother grew so frustrated with her bed alarm that she gave up on sleeping and stayed up late watching television during her hospital stay, said Turner, a researcher at the Moffitt Cancer Center in Florida who studies, among other things, patient safety.

Many hospitals, she said, don’t seem to have evidence-based strategies to reduce falls and, “in the absence of those, they’re using things like bed alarms,” she said, which “is not necessarily reducing falls risk and might actually be causing more harm.”

Dr. Joel Bundy, chief quality and safety officer at Sentara Healthcare, a not-for-profit health system that includes the Virginia Beach hospital, said nurses in that oncology unit decided to use bed alarms for all patients at night because of a high number of falls. But he said Sentara typically employs bed alarms only for patients who are deemed at a high risk of falling, based on a questionnaire developed at Johns Hopkins.

Meanwhile, some hospitals are trying to quiet the noise.

By customizing alarm settings and converting some audible alerts to visual displays at nurses’ stations, Cvach’s team at Johns Hopkins reduced the average number of alarms from each patient’s cardiac monitor from 350 to about 40 per day, she said.

But that’s just one device in one unit; other devices and types of care require different customized settings.

Still, Cvach said, “a lot more can be done.”

Dr. Fred Buckhold, an internist at SSM Health St. Louis University Hospital in Missouri, said one patient’s experience spurred his hospital to reduce reliance on bed alarms.

A 67-year-old woman was placed on a bed alarm while being treated for a collapsed lung, said Buckhold, who wrote about the case in JAMA.

“I feel like I’m in jail,” she protested, Buckhold said. “I can’t sit up or go to the bathroom without them coming after me.”

“Did the bed alarm help her at all?” Buckhold reflected in a recent interview. “It just made her want to kill us.”