Dinah Jimenez assumed a world-class hospital would be better prepared than a chowder house to inform workers when they had been exposed to a deadly virus.

So, when her boyfriend, an employee of a popular seafood restaurant in Seattle, received a call from his boss on a Sunday in late March telling him a co-worker had tested positive for COVID-19 and that he needed to quarantine for 14 days, she said she assumed she’d get a similar call from the University of Washington Medical Center. After all, the infected restaurant employee worked a second job alongside her at the hospital’s Plaza Cafe.

That call never came, she said.

Jimenez, 42, said she returned to her job as a cashier at the hospital cafeteria two days later, and “it was like nothing had happened. They didn’t say anything.” She said the infected worker, a fellow cashier, was stationed just 2 feet from her during a typical shift and that neither had been wearing a mask. “He was as close to me as the person sitting behind you in an airplane,” Jimenez said.

Word slowly spread among the cafeteria crew that a co-worker had the virus, she said. In the days that followed, two more workers fell ill. But communication about the outbreak was not broadly disseminated through the ranks, according to Jimenez and other employees interviewed. It wasn’t until April, Jimenez said, that the hospital started providing workers with one mask per day. A few weeks later, workers said, they learned a fourth staff member had tested positive for the virus.

From cafeteria staff to doctors and nurses, hospital workers around the country report frustrating failures by management to notify them when they have been exposed to co-workers or patients known to be infected with COVID-19. Some medical centers do carefully trace the close contacts of every infected patient and worker, alert them to the exposure and offer guidance on the next steps. Others, by policy, do not personally follow up with health workers who unknowingly treated an infected patient or worked with a colleague who later tested positive for the virus.

“It’s an enormous issue,” said Debbie White, president of the Health Professionals and Allied Employees, a union representing nurses and other health care professionals in New Jersey. “When a patient is positive, our expectation is that the employer would go back and do their due diligence in terms of investigating who was participating in that patient’s care.”

Instead, she said, union members often report “there is very, very little follow-up” to inform them after an exposure.

The disconnect between hospital policy and worker expectations often centers around the lack of clear, direct communication with individual workers who have been potentially exposed to the coronavirus. And when workers are informed about an infected colleague or patient, some say that the efforts to conceal that person’s identity can make it difficult to gauge the level of risk.

Melissa Johnson-Camacho, a nurse at UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, California, said she was informed that another nurse in her unit tested positive, but not which one.

“I don’t know who that nurse is. I don’t know if I had lunch with that nurse. I don’t know if I helped that nurse with a patient,” said Johnson-Camacho, who is a chief nurse representative for the California Nurses Association.

UC Davis Health spokesperson Charles Casey said federal and state privacy laws prevent the hospital from identifying individuals who test positive. HIPAA, the federal privacy rule, does permit some disclosures of personal health information to health care workers during an outbreak of infectious disease, but only the “minimum necessary,” according to recent guidance from the Office for Civil Rights, which is part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Other hospitals contend that because community transmission of COVID-19 is so widespread, workers should assume anyone they encounter, inside or outside the hospital, could be infected and adapt their behavior accordingly.

OHSU Health Hillsboro Medical Center, a major provider outside Portland, Oregon, for example, recently sent an email to all employees saying that because COVID-19 is widespread in that community, “you will no longer receive notification from [the Employee Health program] after caring for a patient with COVID-19. Instead, we ask that you serve as our eyes and ears and report any concerns for exposure to Employee Health as soon as possible.”

Based on similar reasoning, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued updated guidelines in April to say hospitals should consider forgoing contact tracing for their workers — a fundamental of public health work that involves identifying people who have been exposed and asking them to quarantine — in favor of universal masking and screening for symptoms at the beginning of shifts.

While all hospital employees, from food service to custodial staff, are vulnerable to exposure, nurses and other direct-care providers who interact closely with patients are at greatest risk. Informing them of patient exposures is generally less important in intensive care units and wards designated for COVID-19 assessments, where patients are assumed to have the virus and proper protective gear should be used. But when providers care for a patient hospitalized for an unrelated condition who later tests positive, workers say the information can be crucial.

“A lot of nurses are caregivers, too, and we have people at home who are in the high-risk group,” said Johnson-Camacho, the UC Davis nurse. “No one wants to take this home to their family or someone they love.”

Knowing about an exposure might make the difference when deciding whether to hug your children or move out of the family home, Johnson-Camacho added.

At Stroger Hospital in Chicago, nurse Elizabeth Lalasz said she contracted the coronavirus after spending several hours with a patient who came in with what initially was believed to be a chronic respiratory condition, but who later was sent home with a presumed case of COVID-19. Lalasz said the hospital never followed up with her about the presumed exposure, even though she had not been wearing proper protective gear. She said she subsequently fell ill and tested positive for the virus — and that her co-workers were never informed about her condition.

“The contact-tracing idea didn’t even exist,” Lalasz said.

Cook County Health, which operates Stroger, did not directly respond to questions about its policies on informing workers about exposure to the virus. But spokesperson Deborah Song said the system is following CDC guidelines.

At UW Medicine in Seattle, where the cafeteria outbreak played out, spokesperson Tina Mankowski said the hospital is not doing contact tracing when workers or patients test positive for COVID-19. She said that is because the medical center is not asking workers to quarantine at home following a potential exposure.

Under current policy, if an employee contracts the virus, that person’s manager is notified in general terms, and is supposed to share that information with other staff members. Employees are asked to self-monitor for fever or upper-respiratory symptoms, and to stay home if they are ill.

Mankowski confirmed that four cafeteria employees had tested positive for the virus. She said employees were notified but did not provide specifics about how or when.

“The safety of University of Washington Medical Center patients and employees is our top priority,” Mankowski wrote in an email. “If an employee tests positive for COVID-19, the manager is informed that one of their employees has tested positive and then discusses this with the staff in that area.”

Jimenez and three other workers said that was not their experience and that communication about the outbreak was muted.

Luis Rios, a cook at the cafeteria for 17 years, said he was not informed after the first colleague tested positive, though he had chatted with the sick cashier in the staff locker room several times, no more than 2 feet away. A few days after that worker was diagnosed, Rios said, he was taste-testing a dish when he noticed his sense of taste was dulled, a symptom of COVID-19. He also felt cold, even in the warm kitchen. He was tested at an area medical clinic, and became the unit’s second confirmed case.

“Honestly, I don’t know if UW or my managers care about workers’ lives,” said Rios, 49, who spoke through an interpreter. “They only care if we can go in and work.”

Justin Lee, communications director for the Washington Federation of State Employees (WFSE), which represents the cafeteria workers, said supervisors did post a copy of an email from the employee health department to cafeteria directors notifying them in general terms when the first worker tested positive. A printout was tacked near the employees’ time clock. But many workers did not see it or may have been unable to understand it because it was written in English, according to Lee. Information shared days later in a small huddle did not reach the whole staff, he said.

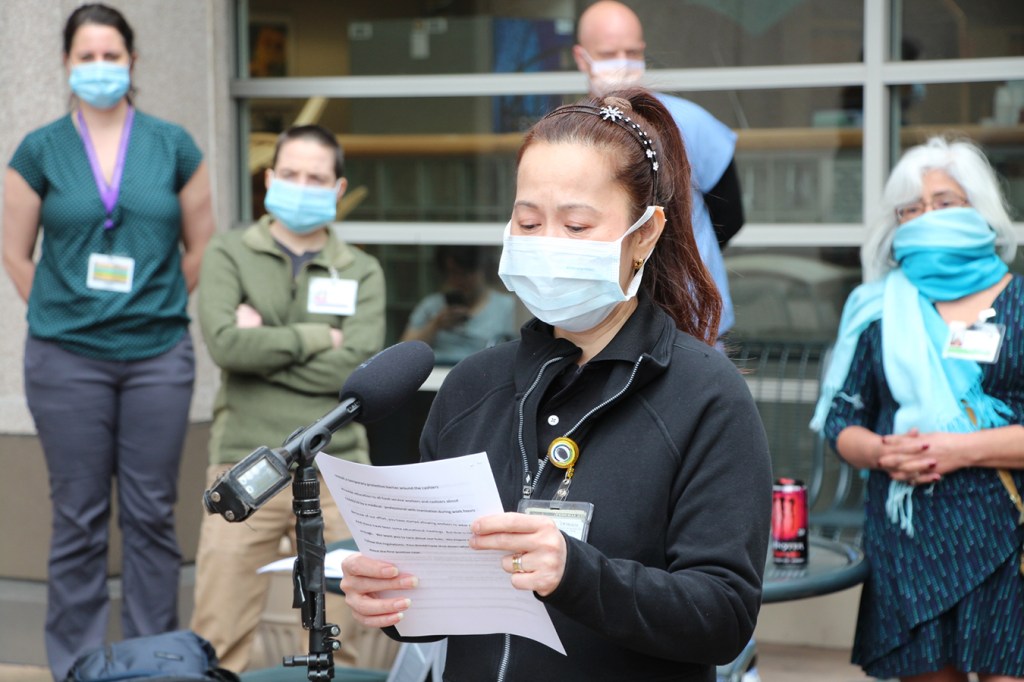

In early April, cafeteria workers delivered a petition to hospital management, with the support of WFSE and Service Employees International Union Local 925, with 450 signatures. They requested the hospital close the Plaza Cafe for a deep cleaning, install a temporary protective barrier around the cashiers and bring in a medical professional to educate all cafeteria staff about COVID-19, with translations in other languages.

The cafeteria was not closed, but Mankowski said the hospital has disinfected it and all workstations, and now requires workers throughout the hospital to wear masks. The hospital has declined to install Plexiglas barriers at the cafeteria, she said, because it believes the universal masking offers the necessary safety precautions.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has no rule requiring that employers inform workers of exposures to infectious diseases. But Dr. Alyssa Burgart, a bioethicist at Stanford, said hospitals do have an ethical obligation. She acknowledged the challenges: With dozens of employees going in and out of a patient’s room each day, tracking every single one can be difficult, particularly with limited resources. Hospitals are trying to figure out in real time exactly what they need to disclose and how to do it.

“Everything is a disaster now, and no one has time to answer anything. So you’re seeing organizations fumble when figuring out how to do this in a way that meets their ethical obligation to protect employees but doesn’t violate federal privacy laws,” Burgart said.

“The typical way these decisions would be made would be over a very long deliberative process, and that is a luxury we do not have right now. Some organizations are going to miss the mark the first time.”