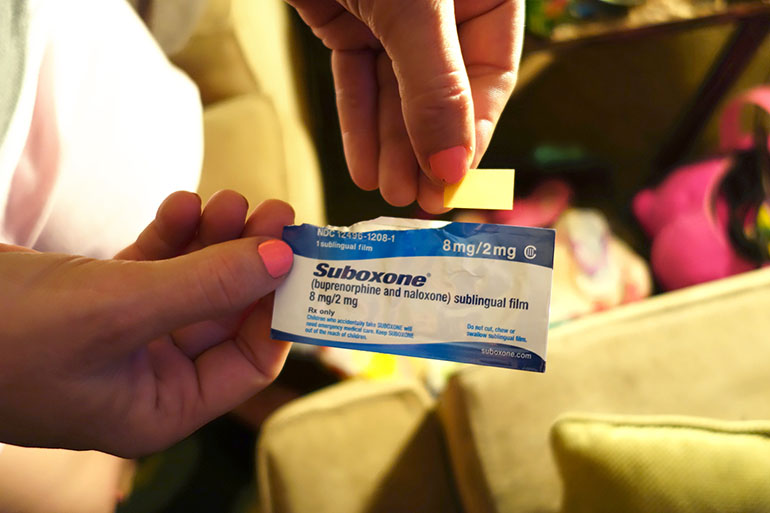

Twice a day, Angela and Nate Turner of Greenwood, Ind., put tiny strips that look like tinted tape under their tongues.

“They taste disgusting,” Angela says.

But the taste is worth it to her. The dissolvable strips are actually a drug called Suboxone, which helps control an opioid user’s cravings for the drug. The married couple both got addicted to prescription painkillers following injuries several years ago, and they decided to go into recovery this year. With Suboxone, they don’t have to worry about how they’ll get drugs, or how sick they’ll feel if they don’t.

“You can function, but you’re not high,” Angela says. “It’s like a miracle drug. It really is.”

A body of evidence now shows that medications such as Suboxone are effective in putting the brakes on opioid use disorder, when used in conjunction with counseling. For the Turners, the treatment means Angela can take care of their 3-year-old and Nate can hold down a job.

But because of some companies’ insurance rules, getting started on Suboxone — and staying on it — can be difficult.

Angela says after her doctor wrote her a prescription, she had to wait three days to get it filled. She spent those days in bed with nausea, diarrhea and muscle cramps — the intense symptoms of opioid withdrawal. For Nate, the wait was five days. On Day 3, he relapsed and used heroin.

“I just thought it was over, that I wasn’t going to make it back to the program,” he says.

Suboxone is covered through the Turners’ health plan, which is part of Indiana’s Medicaid expansion, the Healthy Indiana Plan. But before the couple’s insurance company, Managed Health Services, will pay for the drug treatment, their doctor has to get approval from the insurer — known as a prior authorization.

The prior authorization process adds work for doctors and their staff, said Dr. Andrew Chambers, a psychiatrist and addiction specialist in Indianapolis. With the phone calls, faxing and other paperwork, he said, three of his nurses spend about 30 hours a week going back and forth with the insurance companies.

“It’s almost like when you take on a patient to treat opiate addiction, you also have to take on another patient called the insurance company,” Chambers said.

Getting a prior authorization to prescribe one of these medications can take days or weeks, said Sam Muszynski, director of health care systems and financing with the American Psychiatric Association. He said the delays leave patients vulnerable to relapse.

“You may lose that opportunity right then and there,” he said. “They may never come back.”

Muszynski and policy analysts with the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration say requiring prior authorizations from insurers for addiction medication is a widespread practice in the U.S.

As of 2013, Medicaid in 48 states required a prior authorization for buprenorphine, the active ingredient in Suboxone. Chris Carroll, director of health care financing at SAMHSA, said that number likely has not changed much since 2013. He said treatment limitations like prior authorizations are part of “the dark shadows of the insurance industry.”

Prior authorizations are one way insurers limit what they pay for, Muszynski said, and they use prior authorizations more often with mental health and addiction treatments, compared to other medical treatments. That’s despite the 2008 passage of a federal law called the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, which was supposed to end unequal insurance coverage for mental illness as compared to physical illness.

Nate and Angela Turner, of Greenwood, Ind., take the drug Suboxone twice a day to control their cravings for opioids and heroin. Nate says the drug has helped him hold onto his job and stay in counseling as he works to quit his addiction to painkillers. (Jake Harper/Side Effects Public Media)

For instance, under the Turners’ plan, insulin treatments for diabetes don’t require a prior authorization. But Suboxone does.

“It’s just totally unfair,” Muszynski said. “There’s a continuing pattern of discrimination, which results in reduced access to people who need opioid addiction treatment.”

Prior authorization requirements can also pressure doctors to change how they prescribe a drug such as Suboxone. Sometimes an insurer will push for a lower dosage than the doctor wants, or it will require a patient to start tapering the use of a medication even when the doctor thinks the patient needs more time.

“These rules and regulations for us completely block the correct provision of care,” says Chambers. “And that’s crazy.”

For some insurers, a prior authorization expires after just a few months, forcing everyone involved to go back through the process of reauthorizing. In some cases, Chambers said, patients will even run out of medicine before a new prescription can be approved, which can force them into withdrawal.

Indiana Medicaid said it has started to allow some doctors to skip that initial back-and-forth with the insurance company. But Chambers said the changes haven’t helped him much yet.

Clare Krusing, press secretary with the trade association America’s Health Insurance Plans, said that prior authorizations are not in place to limit treatment for patients with opioid addiction. Rather, she said, they’re meant to ensure that patients receive proper care.

“Prior authorization is not just arbitrarily applied,” she said. “Plans look at what the clinical guidelines are. A plan is going to make sure that before a drug is prescribed, the patient meets those guidelines.”

Krusing added that the prior authorizations in place for buprenorphine don’t violate the parity law, because the treatment plan for addiction is different from the treatment plan for other chronic illnesses, such as diabetes.

Nate Turner has managed to stay in treatment despite the prior authorization process. He says there’s an irony here. He started taking opioids without a prior authorization — in fact, on his plan, the pain pills he used to be addicted to require no prior authorization. He says that sort of gatekeeping paperwork shouldn’t be a stumbling block when he’s trying to quit his opioid habit.

“I can assure you, if I were on regular pain medicine, I’d be able to get them, no problem,” he says. “No questions asked.”

This story is part of a partnership that includes Side Effects Public Media, NPR and Kaiser Health News.