The Medicaid expansion promoted by the Affordable Care Act was a boon for St. Mary’s Medical Center, the largest hospital in western Colorado. Since 2014, the number of uninsured patients it served dropped by more than half, saving the nonprofit hospital more than $3 million a year.

But the Grand Junction hospital’s prices did not go down.

“St. Mary’s is still way too costly,” said Mike Stahl, CEO of Hilltop Community Resources, which provides insurance to about half of its nearly 600 employees and their families in western Colorado. “We are not seeing the decreases in our overall health bills that I believe the community overall should be feeling.”

Stahl and other employers in Colorado hoped that as hospitals saved millions of dollars in charity care from the Medicaid expansion, it would lead to a curb in consumer and employer health costs and insurance premiums.

A new state report found that didn’t happen.

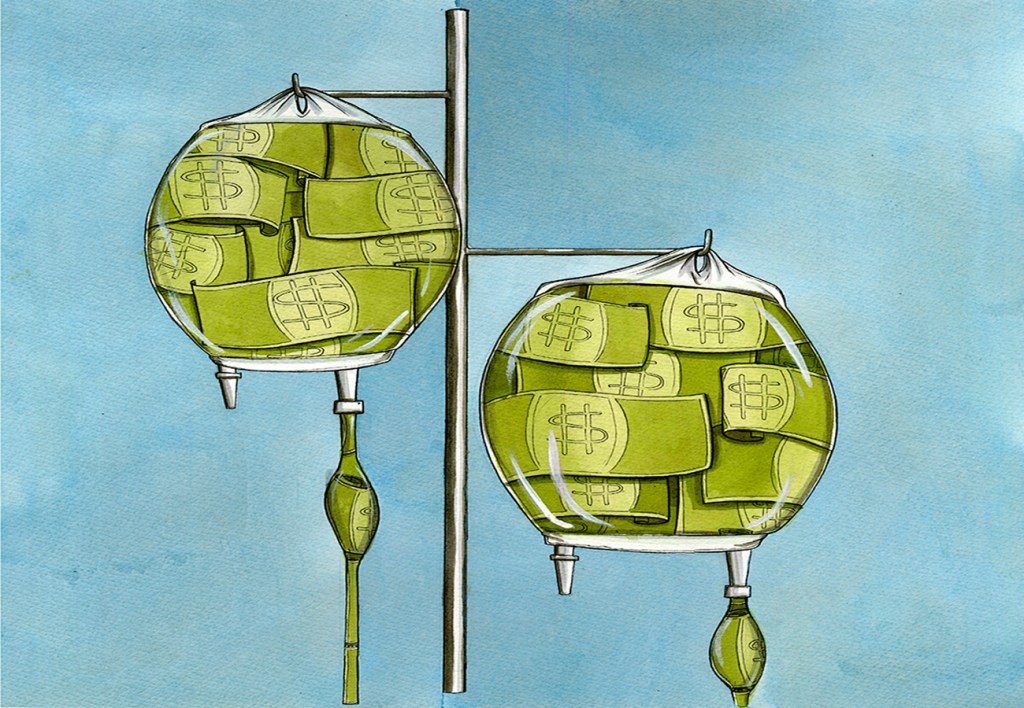

While hospitals are financially better off since the expansion, they have increased the costs they shift to commercial health plans since 2009, the state researchers said.

The state report noted the average hospital profit per each patient discharge rose to $1,359 in 2017, twice the amount in 2009. For patients covered by commercial and employer-based health plans, margins per discharge rose above $11,000 in 2017 compared with $6,800 in 2009.

Julie Lonborg, a spokeswoman for the Colorado Hospital Association, said the state agency that did the study was biased against hospitals and had a “predetermined conclusion.” Hospitals in the state are not doing as well as the report suggests, she added, noting that a third of them face operating losses.

And some insurers have not passed along savings to customers that hospitals give them, she said.

Hundreds of thousands of state residents gained coverage under the Medicaid expansion, lowering Colorado’s uninsured rate by half to 7 percent. In addition, hospitals’ uncompensated care costs dropped by more than 60 percent, or more than $400 million statewide.

Kim Bimestefer, executive director of the Colorado Department of Health Care Policy & Financing, said that hospitals have used their expanded revenues to focus on adding services that provide high profits or expanding operations in wealthier areas of the state that often duplicate what is already available.

“They used those dollars to build free-standing [emergency departments], acquired physician practices, build new facilities where there was already sufficient capacity,” she said. “Hospitals had a fork in the road to either use the money coming in to lower the cost shift to employers and consumers or use the money to fuel a health care arms race. With few exceptions, they chose the latter.”

Hospital’s Profit Margin Doubles

In written testimony to the state legislature last year, Colorado officials pointed to St. Mary’s as an example of a hospital with high overhead and operating costs — factors they said can lead to higher insurance premiums.

The facility’s profit margin was above 14 percent from 2015 to 2017, according to the latest available tax returns. Those figures are nearly double St. Mary’s margin before expansion and twice the margin of the average U.S. hospital in 2017, according to American Hospital Association data.

Colorado is the first state to analyze whether hospital cost-shifting — often referred to as a “hidden tax” on health plans — dropped following Medicaid expansion.

But a conservative think tank in Arizona said hospitals there did not cut prices following that state’s Medicaid expansion.

“Not only did [it] fail to deliver on the promises of alleviating the hidden healthcare tax, it allowed urban hospitals to increase charges on private payers dramatically,” said a report from the Phoenix-based Goldwater Institute.

Some critics point out that hospitals are also benefiting because Congress has repeatedly delayed a key ACA provision that would have cut federal funding for hospitals with large numbers of Medicaid and uninsured patients.

The continuation of the program — called Medicaid disproportionate share payments — has provided Colorado hospitals a total of $108 million.

How Outside Costs May Factor In

The hospital industry disputes reports that it has merely pocketed profits from Medicaid expansion. They say many factors influence how much they charge employers and private insurers, including the need to upgrade technology and meet rising health and drug costs.

Lonborg of the state hospital association said hospitals need to shift costs to private employers to make up for lower prices paid by Medicare and Medicaid and to make up for care hospitals give for free to the uninsured.

But, she added, other factors, including the need to keep up with rapid population growth, have kept costs from dropping.

Janie Wade, chief financial officer for SCL Health, the Broomfield, Colo., hospital chain that owns St. Mary’s and seven other facilities, said its costs are higher because it has sicker and older patients than most.

She said looking at just the hospital profit margins on St. Mary’s IRS-990 form is not a fair assessment because it doesn’t take into account costs that are outside the hospital, such as its 93 physician practices. The hospital lost nearly $12 million on those doctor practices in 2017, she said.

Across all operations, she added, the hospital’s operating margin fell from 9.5 percent in 2015 to 4.5 percent in 2018.

Wade said the hospital used some of its new revenue to purchase 14 physician practices in recent years. That was designed, she added, not to ensure they send their patients to St. Mary’s but to help keep those doctors in the city so they can staff important services such as trauma and maternity care.

“Medicaid expansion was a good thing and, of course, we supported it,” Wade said.

But she pointed out that the hospital loses money on Medicaid and Medicare, which together cover more than three-quarters of its patients.

St. Mary’s has sought to keep price increases for commercial insurers and employers to no more than the general inflation rate and made it even lower for some, according to Wade. If employers’ rates were rising more than that, she said, it was likely because insurers were adding price increases.

Officials from Rocky Mountain Health Plans, which was recently acquired by UnitedHealthcare and is one of Grand Junction’s largest insurers, would not comment.

Dave Roper, who used to oversee employee benefits for the city of Grand Junction and now heads a local employer coalition, said the state report confirms what local businesses leaders have long known. “St. Mary’s has no incentive to reduce its costs,” he said.

Edmond Toy, a senior adviser for the nonprofit Colorado Health Institute, said the argument that pursuing the ACA policy would help lower insurance premiums “broadened the appeal of Medicaid expansion … and conceptually it makes total sense.”

But he noted health experts have long debated whether the higher prices hospitals charge people with private insurance are designed to make up for the losses they take on with Medicare, Medicaid and uninsured patients.

He said the state report shows how hospitals in heavily consolidated markets don’t have to cut prices as their bottom lines improve. “They can charge whatever the market will bear.”

Marianne Udow-Phillips, director of the Center for Health and Research Transformation at the University of Michigan, said hospitals have considerable bargaining power in many places because of health system consolidations and their purchases of many physician practices.

“It does appear Colorado hospitals have a strong negotiating position with payers, or payers there are not negotiating very effectively,” said Udow-Phillips. “Hospitals are not going to give it away.”