How stressful is medical training? So bad that in a class encouraging medical students to express emotion by drawing comics, nearly half depicted their supervisors as monsters.

“In their attempts to make meaning of medical training through images and words, students imagined the workplace as dank dungeons; portrayed patients as ghosts that haunted physicians who had treated them impersonally; represented supervising physicians as fiendish, foul-mouthed monsters; and depicted themselves as sleep-deprived zombies walking through barren post-apocalyptic landscapes,” according to a new article in the Journal of the American Medical Association written by Daniel R. George and Dr. Michael Green, who teach the “Comics in Medicine” class at Penn State College of Medicine.

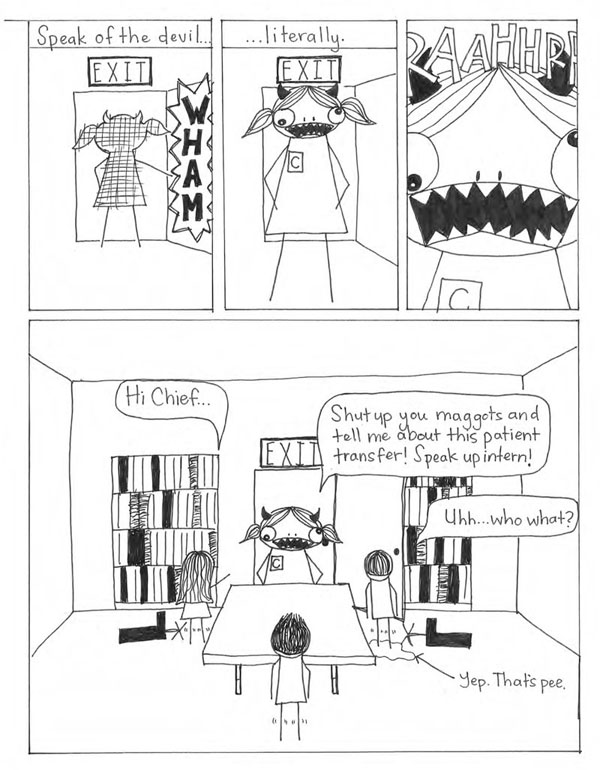

Courtesy of Trey Banbury via JAMA

In one particularly harrowing image, they wrote, a student “depicted his supervising physician screaming at the medical team, causing one intern to urinate herself moments before having her head bitten off for possessing too little information about a patient.”

While the Penn State article encompassed only the 66 students who have taken the humanities class since 2009, a large study in the same annual medical education issue found that nearly one-third of more than 17,000 medical residents in 31 studies screened positive for depression or depressive symptoms. That rate is higher than that for either medical students or practicing physicians who have finished their training, and substantially higher than the rate for the general public.

The study by researchers from several leading medical schools, including Harvard, Yale, and Cambridge in England, added to a body of work showing that the stress of training can cause depression. And it’s not just the doctors themselves who suffer – patients should worry, too. Depression in residents “has been linked to poor-quality patient care and increased medical errors,” the researchers note.

The two studies together demonstrate that something is wrong with the training system in general, University of Nevada Medical School Dean Thomas Schwenk says in an accompanying editorial.

“The profession purportedly recognizes the importance of health and wellness,” Schwenk wrote, “but the value system of the current training environment makes clear to residents the unacceptability of staying home when ill, of asking for coverage when a child or parent is in need, and in expressing vulnerability in the face of overwhelming emotional and physical demands.”

A big part of the problem is that medicine has long been taught by treating underlings harshly – which has been considered acceptable because a mistake could cost a patient her life.

“People treat people like they were treated,” said Green, a physician and professor of internal medicine at Penn State, in an interview. “This is how I did it and I’m OK, so I’m going to do it to you and you’ll be OK.”

But medicine itself has changed, Schwenk said in an interview, and that compounds the problem. “My era (the 1970s) came away with very strong role models and people who were incredibly influential,” he said. “Today everyone is so frantic” with patients moving in and out of hospitals faster and many more strict protocols for patient care. That leaves little time or space for more benevolent types of supervision and teaching for doctors-in-training.

So what would help?

Schwenk says it’s time for the pendulum to swing back toward more personalized training after medical school. “There’s got to be a shift back toward dedicated teaching and mentorship,” he said. “We’ve lost that because of the craziness of the (health) system.”

Doctors who train other doctors also need to practice what they preach, he says. “We don’t teach in ways that encourage wellness and good mental health and coping mechanisms.”

Green says the system also needs to be geared toward stopping the abuse of medical students and residents by professional superiors.

“There has to be a message that this is not OK and there will be consequences for treating people badly,” he said.

But both doctors said they hope that bringing more visibility to the problem could help lead to needed changes. Said Green: “My hope is it’s getting better because we’re much more sensitized to these issues.”