A study released Thursday challenges two widely-held assumptions about medical care: that people who see a primary care physician will end up healthier than those who don’t, and that having more primary care doctors in an area guarantees better access for patients.

Dartmouth researchers found that people on Medicare who saw a primary care doctor at least once a year were just as likely to end up in the hospital for a chronic illness as those who didn’t have a regular checkup or visit. A visit to a primary care physician didn’t make it any less likely that someone with serious diabetes or peripheral vascular disease would get a leg amputated, their study concluded.

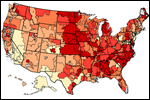

Map: Percent of Medicare Beneficiaries Who Had At Least One Visit to a Primary Care Clinician

Source: The Dartmouth Atlas Project

The health reform legislation passed this year by Congress aims to improve access to primary care, in large part by expanding insurance coverage. But Dr. David Goodman, the study’s lead author, said the findings signal that the nation needs to do more than just get patients into a primary care doctor’s office–it also has to ensure physicians coordinate care with specialists and hospitals.

“While primary care may be necessary for good care, it’s not sufficient by itself,” Goodman said in an interview. “Primary care is not always practiced effectively. It can be disorganized and disconnected from other parts of care.”

The study also found that blacks were worse off than whites in a variety of ways: they are less likely to see a primary care physician, more likely to be hospitalized and more likely to have a leg amputated.

Researchers with the Dartmouth Atlas Project looked at Medicare data between 2003 and 2007 and found that nationally, 77.6 percent of beneficiaries saw a primary care physician or nurse practitioner at least once a year. But that rate varied greatly depending on geography: Only about 60.2 percent of Medicare beneficiaries in the Bronx had an annual visit, while nearly 88 percent did so in Florence, S.C.

The researchers found that some areas with relatively few primary care physicians, such as Wilmington, N.C., still had high rates of visits, while other areas with plenty of such doctors, such as White Plains, N.Y., had lower than average rates for annual visits.

The researchers did identify some benefits that came from annual doctor’s visits. Female Medicare beneficiaries between ages 67 and 69 who saw a primary care physician annually were more likely to get a mammogram once every two years. Diabetics were more likely to get A1c hemoglobin blood tests to measure how their blood sugar was controlled. But they were no more likely to get blood lipid testing or eye examinations, two other tests that are recommended by the American Diabetes Association.

The study did not look at whether health outcomes improved when people saw their primary care doctor more often than once a year. A wide range of previous studies has shown that regular visits to primary care doctors have helped patients avoid hospitalizations and made it more likely they take their medications appropriately, said Dr. Ann O’Malley, a senior researcher at the Center for Studying Health System Change, a Washington think tank.

O’Malley agreed with Dartmouth’s conclusion that improving results will require changing the way medical providers are paid so that primary care doctors, specialists and hospitals all have incentives to coordinate care, rather than just do more. “We can’t expect primary care to save everybody on its own,” she said.

jrau@kff.org