House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan, R-Wis., left many details to Congress when he unveiled Tuesday his plan to make major changes to Medicare as part of a fiscal 2012 budget resolution. He says his overall objective is to convert Medicare into a premium support program for which the government will spend a specific amount for beneficiaries’ care, a fundamental shift from the current fee-for-service program. Backers of premium support say it is similar to the health insurance program for federal workers but others say it may not meet seniors’ needs. Insurers are eager for the additional business but wonder if payments will be adequate to cover the cost of care. Here is a guide to some of the issues and questions raised by Ryan’s plan, which faces enormous political hurdles given expected Democratic opposition.

What is premium support?

A premium support model would fundamentally change the way that Medicare works by limiting the amount of money the federal government spends on medical services for seniors and the disabled. Currently, Medicare is an entitlement program, which means that the government must help finance every doctor visit and medical service that an individual needs.

Under a premium support system, the government would pay a percentage toward the insurance premium for each individual; there would likely be more help for low-income and sicker people. And enrollees could kick in more money to get better coverage.

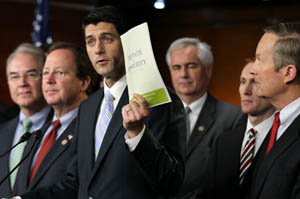

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Henry Aaron, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and Robert Reischauer, president of the Urban Institute and former head of the Congressional Budget Office, in 1995 were among the first to explore alternatives to Medicare’s system of paying for individual services. And in 1998, President Bill Clinton’s National Bipartisan Commission on the Future of Medicare, chaired by then-Rep. Bill Thomas, R-Calif., and then-Sen. John B. Breaux, D-La., developed a “premium support” idea, but it never became a formal recommendation. Breaux and then-Sen. Bill Frist, R-Tenn., tried unsuccessfully to advance the plan as separate legislation.

Today, there are many ways to shape the model. “In past iterations, the idea of premium support involved having government pay a share of the premium for a defined set of benefits. But the concept is not locked in stone, and sponsors can clearly modify it with various bells and whistles,” said Tricia Neuman, vice president of the Kaiser Family Foundation. “These variations can have huge implications for both beneficiaries’ spending and for federal savings.” (KHN is a program of the foundation.)

One variable is how much federal spending would increase each year. “We don’t want spending per person to grow disproportionately fast or slow because of things like variations in birth rates 65 years ago,” said Joe Antos, the Wilson H. Taylor Scholar in Health Care and Retirement Policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute. “It wouldn’t be bad to put some number up there, but every year or every five years Congress could take a look at it and say, ‘This is what we want.'”

Is premium support anything like vouchers?

Ryan argues there are important distinctions, and some conservative policy experts agree.

In a voucher plan the government would cut a check and then allow seniors to buy the insurance policies they want in the private marketplace. Ryan acknowledged on Fox News Sunday that his Medicare proposals over the past several years included vouchers, but he recommended premium support in his budget Tuesday.

Plans And Proposals

A premium support model could resemble the existing system for federal employees, said Gail Wilensky, who oversaw Medicare for President George H.W. Bush and is now a senior fellow at Project Hope. Like vouchers, it limits government contributions, but also bases the amount on the premium costs of popular, participating health plans. “That gives you assurances that there will be a low-cost plan that can be purchased,” she said.

Others counter that premium support and vouchers are the same thing. “I use the words interchangeably,” said John Goodman, president of the National Center for Policy Analysis, a conservative think tank in Dallas. “It just means that the government limits the amount of money that it puts up, and people have to add to it if market prices are higher.”

It’s not surprising that Republicans favor the term premium support, as the word voucher elicits a strong negative reaction from the public. A September poll conducted by Pew Research and National Journal found that 69 percent of people older than 65 opposed vouchers for Medicare. That opposition came from both Democrats and Republicans.

How does the Ryan plan compare to the federal employees’ health plan?

Thomas Buchmueller, a health economist at the University of Michigan, said the plan sounds much like the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program but also like the exchanges being set up in the health law. In the FEHBP model the government provides a set financial contribution each year.

Employees and retirees have a variety of options, from catastrophic coverage plans with high deductibles to health maintenance organizations to high-end plans with many choices of doctors. Everyone has a choice of at least 10 fee-for-service plans, but the exact number varies by where an enrollee lives.

FEHBP provides coverage without regard to pre-existing conditions or age. On average, the government pays 72 percent of premiums.

Analysts and advocates have sharply opposing views on the merits of an FEHBP approach vs. traditional Medicare.

Medicare supporters say it has lower administrative costs than the FEHBP. But Michael Tanner, senior fellow with the libertarian Cato Institute in Washington, said the comparison is misleading because Medicare outsources some of its jobs to other parts of government such as the Internal Revenue Service, which collects Medicare taxes.

Jonathan Oberlander, professor of social medicine at University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, said FEHBP generally has had trouble controlling health costs over the past decade. But in 2011, its rates for the enrollee share of premiums increased by an average of 7.2 percent. That figure is below last year’s 8.8 percent increase and lower than rate hikes predicted this year for large, employer-sponsored health programs by major benefit consultants.

Tanner said FEHBP is not perfect but is preferable to the current system because it would reduce federal spending on Medicare.

Buchmueller sees pros and cons to the Ryan plan. “On the positive side is that you are adding price incentives at the consumer level so that can be translated to incentives on plans to control health costs,” he said. The risk is that many seniors are not that price sensitive.

Oberlander said putting all Medicare beneficiaries in a system where they have to shop for coverage would be confusing for many of them. “The idea of Medicare beneficiaries acting like rational consumers in a medical marketplace is farfetched,” he said.

“Premium support is a euphemism for increasing costs for Medicare beneficiaries,” Oberlander said.

What do Democrats think of premium support?

Expect many Democrats to oppose any effort to turn the Medicare program from its current structure, which guarantees a specific set of benefits, into a program that designates a set amount of funding for beneficiaries. They fear the “premium support” approach will require beneficiaries, many of whom live on fixed incomes, to pay more for their medical care. That said, some conservative Democrats worried about the growing federal deficit and debt may back the plan if they think it’s done in a reasonable way and will help control Medicare spending. Alice Rivlin, who co-authored a Medicare overhaul plan with Ryan and was budget director for President Clinton, said the “premium support” concept has backers in both parties. “It doesn’t strike me as a particularly Democratic or Republican idea once you think that you need to do something,” she said.

What do insurers and industry analysts say about the idea?

It could be a boon for the industry, providing millions of new customers. “It’s a lot of new business,” said Ana Gupte, a Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. analyst.

But there are many questions about how the program would be structured. “We don’t have a lot of details on what they’re talking about,” Mark Bertolini, president and CEO of Aetna, said Monday.

Some of the unanswered questions include the dollar amount each enrollee would have to purchase insurance and how much that would rise in future years. Would it go up only with general inflation, by the much higher medical inflation rate, or something in between? Tying the annual increase to general inflation would save the government money, but cost consumers more.

Other questions include whether all insurers would be able to offer coverage, or only those who meet certain price and quality benchmarks. How the program would save money is also unclear.

Robert Laszewski, a Virginia-based consultant to the health care industry, said any Republican plan would likely include all insurers. “It would be along the lines of ‘here’s the voucher and there’s the market,” he said, adding that Republicans might create some kind of standard benefit package, but allow insurers to offer a wide range of policies in addition to a standard package. He isn’t sure how it would save money, based on the experience with private insurers in Medicare Advantage, which offers an alternative to traditional Medicare.

Those plans on average cost taxpayers more than traditional Medicare. The health law approved by Congress last year begins ratcheting down the extra payments to Medicare Advantage to bring them in line with the traditional program. At present, Medicare Advantage insurers enroll about 24 percent of all beneficiaries.

This article was written by Julie Appleby, Mary Agnes Carey, Phil Galewitz, Marilyn Werber Serafini and Christopher Weaver.