Republicans are in a hurry to get their “repeal and replace” health care bill to the House floor.

In just the week since it was introduced, two committees have approved the “American Health Care Act,” and a floor vote is planned before month’s end.

But in the rush to legislate, some facts surrounding the bill have gotten, if not lost, a little buried. Here are five things that are commonly confused about the health overhaul effort.

1. The GOP bill would replace the health law’s subsidies with tax credits.

Not really. The GOP bill would replace the Affordable Care Act’s tax credits with different tax credits.

Under the ACA, people with income above the poverty line (about $12,000 for an individual in 2017) and under four times the poverty line (about $47,000) who buy their own insurance are eligible for advanceable, refundable tax credits. “Advanceable” means they don’t have to wait to file their taxes, so the money is available each month to pay premiums; “refundable” means credits are available even to those with incomes too low to owe federal income tax. The ACA’s tax credits are based on income and the actual price of health insurance available to each individual.

The GOP bill also has advanceable, refundable tax credits. They are based on different criteria, though. The Republican tax credits would increase with age (from $2,000 for youngest adults to $4,000 for older adults not yet eligible for Medicare), and would gradually phase out with income (starting at $75,000 for individuals and $150,000 for families). They would not vary by geographic region or the cost of coverage. And while older adults would get credits twice as large as younger adults, another change in the bill would let insurers charge those older customers’ premiums that are five times as high. In the current law, the difference is 3-to-1.

There are actual subsidies in the ACA — they help people with incomes between 100 and 250 percent of poverty ($12,060 to $30,150 for an individual) pay their deductibles and coinsurance or copays. These subsidies are the subject of an ongoing lawsuit filed by the House against the Obama administration. Those subsidies would be repealed under the GOP bill.

2. Republicans have left popular provisions of the ACA in their bill because they are popular.

Not necessarily. True, the public supports the provisions of the health law that allow adult children to stay on their parents’ health plans until they turn 26 and that prohibit insurers from rejecting or charging more to people with preexisting health conditions. Those things remain in the GOP bill.

But even if Republicans had wanted to get rid of those provisions, they likely could not. That’s because the budget rules Congress is using to avert a filibuster in the Senate forbid them from repealing much of the ACA that does not affect government spending.

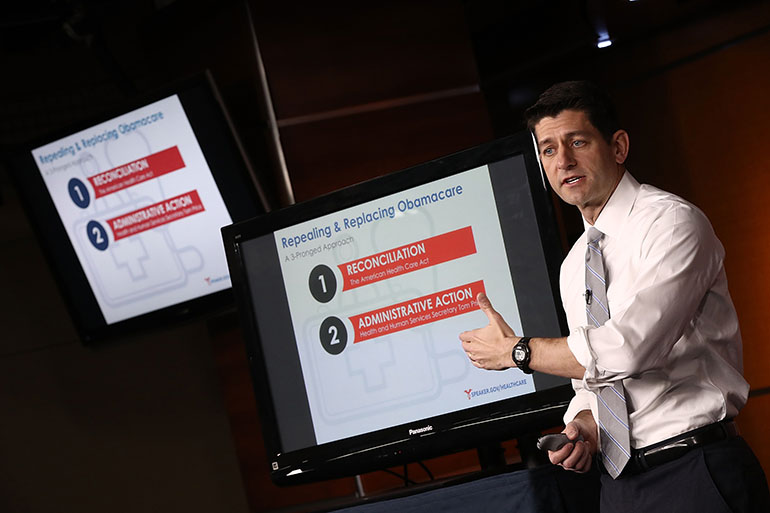

3. This bill is one part of a three-part effort to remake the health law.

This is true; Republicans continually refer to their health care effort as having three “buckets.” One is the budget bill currently under consideration. A second is the power of Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price to make administrative changes that would undermine the ACA.

The third is follow-up legislation that would allow things like selling insurance across state lines and limiting damages in medical malpractice lawsuits. House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-Wis.) referred to that in a Thursday press conference as “additional legislation that we feel is important and necessary to give us a truly competitive health care marketplace.”

What Republicans usually don’t say, though, is that the second and third parts are complicated. Changing federal regulations generally requires a cumbersome process of advertising the changes, soliciting comments and revising the rules. Controversial changes also can bring lawsuits and lengthy legal proceedings. In addition, any subsequent bills on the law would require 60 votes to pass the Senate because they would not be covered by the budget rules Republican are using for this first legislation. Republicans currently have a 52-48 vote majority in that chamber, and Democrats have so far been united in opposing the GOP’s health changes.

4. The bill’s Medicaid provisions just scale back the program’s expansion.

In truth, the Medicaid portions of the GOP bill would fundamentally restructure the Medicaid program.

The Affordable Care Act allowed states to expand Medicaid, whose cost is shared between the states and federal government, to everyone with incomes under 138 percent of poverty. Previously, eligibility was restricted to those in specific categories (primarily low-income pregnant women, children, seniors and those with disabilities). Because Medicaid was already a significant financial burden for states, the federal government offered to pay the entire cost for the expansion population for the first three years, eventually dropping back to 90 percent, which is still more than states get for traditionally eligible populations.

The GOP bill would end new enrollment in that expanded program in 2020. It would continue to cover people who had already qualified — but since many people in Medicaid churn in and out of the program, the number of enrollees is likely to gradually decline.

But that’s just the beginning of the Medicaid changes. The Republican bill would, for the first time ever, limit the amount the federal government provides to states for Medicaid spending. It would make payments based on the number of enrollees in each state and that “per-capita” cap is expected over time to shift more financial responsibility for the program to the states. The left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities estimates that states could be on the hook for an additional $370 billion over 10 years if the bill becomes law.

5. The GOP bill is a huge tax break for the wealthy.

This is technically true — the bill would provide nearly $600 billion in tax breaks over the next decade, almost all of it going to the wealthy, according to the nonpartisan Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

But that’s not because Republicans set out to lower taxes on wealthy people. It’s because they are repealing nearly all the taxes that helped pay for the health law’s benefits, and the Democrats had targeted many of those to higher-income people.