MOUNTAIN VIEW, Ark. — Hospital pharmacist Mandy Langston remembers when Lulabelle Berry arrived at Stone County Medical Center’s emergency department last year.

Berry couldn’t talk. Her face was drooping on one side. Her eyes couldn’t focus.

“She was basically unresponsive,” Langston recalls.

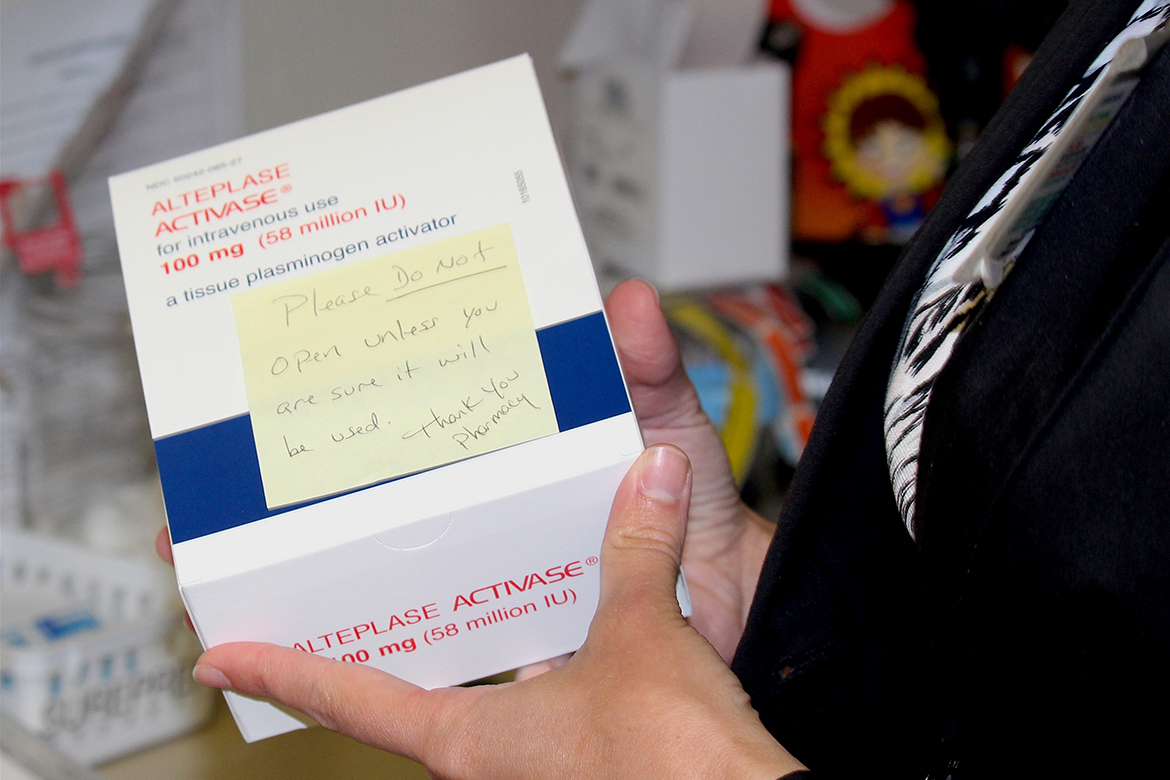

Berry, 78, was having a severe ischemic stroke. Each passing second made brain damage more likely. So, Langston reached for the clot-busting drug Activase, which must be given within a few hours to work.

“If we don’t keep this drug [in stock], people will die,” Langston said.

Berry survived. But Langston fears others could die because of an unintended bias against rural hospitals built into the U.S. health law. An obscure Obamacare provision forces rural hospitals like Langston’s to pay full price for drugs that many bigger hospitals buy at deeply discounted rates.

For example, Langston’s 25-bed hospital pays $8,010 for a single dose of Activase — up nearly 200 percent from $2,708 a decade ago. Yet, just 36 miles down the road, a bigger regional hospital gets an 80 percent discount on the same drug.

White River Medical Center, a 235-bed facility in Batesville, Ark., buys Activase for about $1,600 per dose. White River participates in a federal drug discount program Congress approved in the early 1990s. The program offers significant price breaks on thousands of drugs to hospitals that primarily serve low-income patients. One federal report found the average discount ranged from 20 to 50 percent, though as illustrated with Activase, it can be much higher.

Rural hospitals have long wanted to be part of the so-called 340B program, too, but were blocked from participating until the Affordable Care Act of 2010. That historic health law added rural hospitals to the overall program. But, unlike bigger hospitals, rural hospitals can’t get discounts on expensive drugs that treat rare diseases because of a last-minute exclusion written into the ACA.

That seemingly minor detail in the law has left rural hospital pharmacists and health care workers struggling to keep medicines in stock, and wondering if they will be able to adequately care for patients.

Arkansas, for example, is in the “stroke belt,” where medical staff depend on Activase to help them battle one of the highest rates of stroke deaths in the country. When Langston went to restock Activase this year, it was so expensive she left a reorder unfilled for more than week, anxiously keeping only one dose of the clot-busting drug on hand.

“Usually strokes come in clusters,” Langston said. “I didn’t want two people to come in and we were going to [have to] choose which one we were going to treat.”

In Atlantic, Iowa, pharmacy director Crystal Starlin sparingly stocks oncology drugs at Cass County Memorial Hospital. Newly diagnosed cancer patients might have to wait a couple of days to start treatment.

“We just can’t keep the extra [drugs] on hand,” Starlin said.

In Vermont, North Country Hospital closed its infusion center this spring due to the soaring cost of medicines.

“That was one area we could not afford to be in,” said chief executive Claudio Fort. North Country is the only hospital in a two-county region along the Canadian border and its roughly dozen active chemotherapy patients now must drive 45 minutes away for treatment.

The rare-disease exclusion was not publicly debated before being added into the ACA. Rather, it was tucked into the law at the very end of the process. How it wound up in the law is a bit of a mystery.

Former PhRMA chief executive Billy Tauzin said he doesn’t recall negotiating the exclusion. But, he said, the industry has consistently raised concerns about the drug discount program’s reach.

“It’s a question of how deeply you can afford to discount drugs that are expensive,” said Tauzin, who abruptly stepped down just before the ACA passed.

After the health law passed, PhRMA battled for years — in federal court — to keep rural hospitals from getting discounts on rare-disease drugs.

Congressman Peter Welch, a Democrat from Vermont who represents North Country, said it is clear whom the law hurts and helps.

“The pharma lobbyists pay attention, and their lawyers pay attention to the fine print,” Welch said. The pharmaceutical industry “changes that fine print … [and] many legislators don’t even realize [that it] will have this adverse impact on hospitals in their communities.”

The rare-disease exclusion means that certain types of hospitals — including critical access, sole community and rural referral centers — cannot get discounts on rare-disease drugs, or on drugs that are “designated” to treat a rare disease. (Rare-disease drugs are also known as orphan drugs, which is a federally approved category of drugs that treat a disease affecting fewer than 200,000 people. Often, they carry price tags of up to $100,000 a year or more.)

The Food and Drug Administration gives the designation as a first step when it agrees with a drugmaker’s request to study whether a drug can be used to treat a specific rare disease. This can happen even if a drug is already FDA-approved and on the market for use in treating a common condition. The next step — the ability to market the medicine as an orphan drug — comes once research confirms that the drug is safe and effective in treating a specific, less common condition.

The popular clot-buster Activase has not won final approval to treat a rare disease but, on two separate occasions in 2003 and 2014, the FDA has given it the orphan designation while research is ongoing.

About 450 orphan drugs have been approved by the FDA. But thousands of drugs are “designated” and more are identified every week.

The list includes generic drugs such as the hormone melatonin and the autoimmune drug abatacept. In other words, medicines used to treat everything from sleep troubles to arthritis have ended up “designated.”

The small town of Mountain View, Ark., known for its crafts and music scene, is about two hours north of Little Rock and nestled in the rolling Ozarks. Arkansas’ mountainous terrain makes it essential for local hospitals to stock lifesaving stroke drugs. The state reports some of the nation’s highest rates of stroke deaths. (Sarah Jane Tribble/KHN)

Some drugmakers, such as Janssen Pharmaceuticals, have voluntarily offered discounts to rural hospitals on all of their orphan drugs including Remicade, whether they’re approved or designated. In contrast, drugmaker Genentech sent letters to rural hospitals on Jan. 1 listing dozens of drugs that would not qualify for discounts, including Activase and cancer drug Avastin.

Susan Willson, a Genentech spokeswoman, said the company is “deeply committed to ensuring that people have access to the medicines they need.” But, she added, the company believes the federal drug discount program has “grown well beyond its original intent.”

Several federal reports in recent years from the Medicare advisory board, as well as the Government Accountability Office and the Office of Inspector General, have evaluated the federal drug discount program’s growth. About 40 percent of U.S. hospitals now participate in the program and House Republicans held a hearing this summer questioning the program’s growth.

But for Dana Smith, director of pharmacy at Dallas County Medical Center in Fordyce, Ark., the discount program’s growth and problems are a separate issue.

“Basically, Genentech is saying to me that rural health care and the patients in rural America are not as important as patients in urban areas,” Smith said, adding the pharmaceutical industry “knows we have less manpower to fight them.”

Back at Stone County, emergency room medical director Dr. Barry Pierce paused one recent afternoon at the nursing station and recalled those tense days with just one dose of Activase. Stone County now keeps two doses of the stroke drug on hand.

Pierce noted that Stone County is at least 45 minutes away from the next nearest hospital and, echoing Langston’s concern, he said: “If we don’t have the drugs we need, people will die.”

KHN’s coverage of prescription drug development, costs and pricing is supported in part by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation.