The federal government will pay more than $100,000 to give someone a kidney transplant, but after three years, the government will often stop paying for the drugs needed to keep that transplanted kidney alive.

Constance Creasey is one of the thousands of people who find themselves caught up by this peculiar feature of the federal kidney program.

Creasey started kidney dialysis about 12 years ago after her kidneys failed. That meant going to a dialysis center three times a week, for three hours per session. (A typical patient undergoes three to five hours of dialysis per session).

“The first three years of dialysis was hard. I walked around with this dark cloud. I didn’t want to live, I really didn’t,” she says.

Being dependent on these blood-cleansing machines was physically and emotionally draining. But she stuck it out for 11 years. Medicare pays for dialysis, even for people under the age of 65. It also pays for kidney transplants for people with end-stage renal disease.

“Finally, a year and a half ago, transplant came. I was a little apprehensive but I said OK. And I call her Sleeping Beauty, that’s my kidney’s name.”

Creasey, a 60-year-old resident of Washington, D.C., no longer needs to spend her days at a dialysis center. She has enough energy for a part-time job at a home furnishing store and time to enjoy life’s simple pleasures.

“I was able to do my favorite thing — go to the pool — and I was just loving it because it’s like I had no restrictions now,” she says.

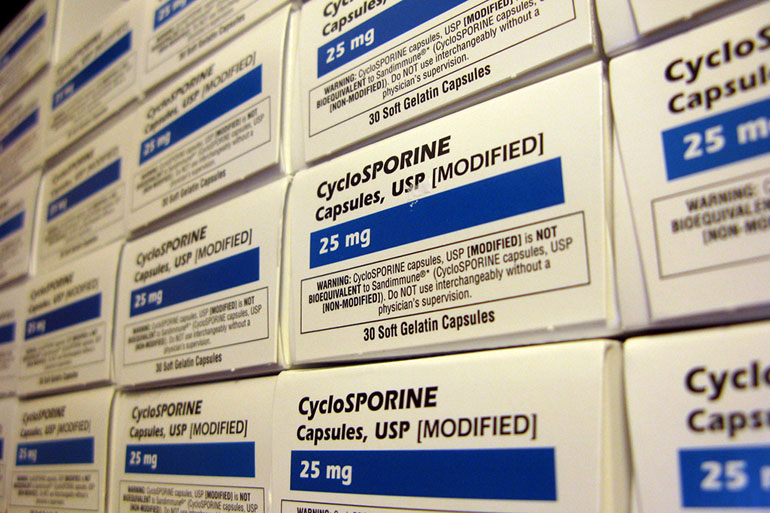

But there is still a dark cloud on Creasey’s horizon. Medicare’s kidney program currently pays for a large share of the expensive drugs she needs to take twice a day to prevent her body from rejecting the transplanted kidney. But under federal rules, that coverage will disappear three years after the date of her transplant.

“I have a year and a half to prepare, or save,” she says. “How am I going to do this?”

She’s already paying copays, premiums and past medical bills. She says she sleeps on the floor because she considers buying a bed a luxury she can’t afford.

She has no idea what kind of insurance she’ll be able to get after her Medicare coverage runs out. And she was shocked to discover how big the bills could be. One day she went into the pharmacy to pick up her drugs, and the Medicare payment hadn’t been applied.

The pharmacist told her she’d need to pay a $600 copay for the one-month supply. “And I’m like are you kidding me? Six hundred? What am I going to do? I can’t pay that!”

A social worker at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital in Washington, D.C., where Creasey got her transplant, sorted that out. But it’s not a permanent solution.

The three-year cutoff for Medicare payments is a common problem, says Dr. Matthew Cooper, who runs the kidney transplant program at the hospital. That’s especially so since many people with serious kidney disease have low incomes in the first place.

“It’s probably about 30 percent of people who find themselves in a troublesome spot at this 36-month mark,” he says.

Some people end up trying to stretch out their drug supplies by not taking them as often as they need to, he says. “We see that a lot.”

But this isn’t like skipping a pain pill and bearing the consequences. People lose their transplanted kidneys through organ rejection if they don’t take their medicine religiously.

Rita Alloway, a clinical pharmacist at the University of Cincinnati, says she also encounters this false economy. “If we were telling them to take four pills twice a day, they may start taking three pills twice a day without telling us, to extend their coverage that they had for the prescriptions they had,” she says.

If people tell her that they can’t afford it, she can help them get the medications for free, Alloway says. But sometimes people are too proud to admit their financial distress, she said.

And instead of spending $15,000 a year on these anti-rejection drugs, people go back onto dialysis, which costs $90,000 a year or more. And that’s taxpayers’ money, provided with no time limit.

Kevin Longino, CEO of the National Kidney Foundation, says it’s not just affecting the people who have transplants, but those who are on the long list waiting their turn for an organ to become available.

“The tragedy is you have so many people on the wait list already, and to have someone unnecessarily have rejection because they can’t afford the drugs and to have to go back into the system — it’s just a difficult thing to explain, why we’re allowing that to happen.”

Longino says insurance companies are making the problem even worse. Some have reclassified anti-rejection drugs as “specialty drugs,” and they now require patients to pay for a percentage of the cost, rather than a more traditional fixed copayment.

Longino encountered that himself after he had a kidney transplant about a dozen years ago. He says his costs went from $150 a month to $950 a month when his insurance company made that cost-sharing shift.

He, Alloway and Cooper have been trying to persuade Congress to pass a bill to fix this problem. Rep. Michael Burgess, R-Texas, and Rep. Ron Kind, D-Wis., have introduced bills more than once, but they have not moved through Congress. Burgess’ office says they plan to try again next year.

Lawmakers are concerned about the costs. Severe kidney disease already costs Medicare a staggering $30 billion a year, and there’s no official cost-benefit analysis showing whether covering transplant drugs for everybody would save money overall.

“The Medicare [savings] in maintaining this drug coverage is better than putting people on dialysis,” Cooper says. “To me this is a no-brainer. I just cannot understand why we haven’t got to the point where we say Medicare coverage for life for immunosuppressive drugs because people will benefit and money will be saved.”

For Constance Creasey, this is not an abstract conversation.

“Those pills are my life right now,” she says. “I’m trying not to worry, but it’s hard.”