Voters this year have told pollsters in no uncertain terms that health care is important to them. In particular, maintaining insurance protections for preexisting conditions is the top issue to many.

But the results of the midterm elections are likely to have a major impact on a broad array of other health issues that touch every single American. And how those issues are addressed will depend in large part on which party controls the U.S. House and Senate, governors’ mansions and state legislatures around the country.

All politics is local, and no single race is likely to determine national or even state action. But some key contests can provide something of a barometer of what’s likely to happen — or not happen — over the next two years.

For example, keep an eye on Kansas. The razor-tight race for governor could determine whether the state expands Medicaid to all people with low incomes, as allowed under the Affordable Care Act. The legislature in that deep red state passed a bill to accept expansion in 2017, but it could not override the veto of then-Gov. Sam Brownback. Of the candidates running for governor in 2018, Democrat Laura Kelly supports expansion, while Republican Kris Kobach does not.

Here are three big health issues that could be dramatically affected by Tuesday’s vote.

1. The Affordable Care Act

Protections for preexisting conditions are only a small part of the ACA. The law also made big changes to Medicare and Medicaid, employer-provided health plans and the generic drug approval process, among other things.

Republicans ran hard on promises to get rid of the law in every election since it passed in 2010. But when the GOP finally got control of the House, the Senate and the White House in 2017, Republicans found they could not reach agreement on how to “repeal and replace” the law.

This year has Democrats on the attack over the votes Republicans took on various proposals to remake the health law. Probably the most endangered Democrat in the Senate, Heidi Heitkamp of North Dakota, has hammered her Republican opponent, U.S. Rep. Kevin Cramer, over his votes in the House for the unsuccessful repeal-and-replace bills. Cramer said that despite his votes he supports protections for preexisting conditions, but he has not said what he would do or get behind that could have that effect.

Polls suggest Cramer has a healthy lead in that race, but if Heitkamp pulled off a surprise win, health care might well get some of the credit.

And in New Jersey, Rep. Tom MacArthur, the moderate Republican who wrote the language that got the GOP health bill passed in the House in 2017, is in a heated race with Democrat Andy Kim, who has never held elective office. The overriding issue in that race, too, is health care.

It is not just congressional action that has Republicans playing defense on the ACA. In February, 18 GOP attorneys general and two GOP governors filed a lawsuit seeking a judgment that the law is now unconstitutional because Congress in the 2017 tax bill repealed the penalty for not having insurance. Two of those attorneys general — Missouri’s Josh Hawley and West Virginia’s Patrick Morrisey — are running for the Senate. Both states overwhelmingly supported President Donald Trump in 2016.

The attorneys general are running against Democratic incumbents — Claire McCaskill of Missouri and Joe Manchin of West Virginia. And both Republicans are being hotly criticized by their opponents for their participation in the lawsuit.

Although Manchin appears to have taken a lead, the Hawley-McCaskill race is rated a toss-up by political analysts.

But in the end the fate of the ACA depends less on an individual race than on which party winds up in control of Congress.

“If Democrats take the House … then any attempt at repeal-and-replace will be kaput,” said John McDonough, a former Democratic Senate aide who helped write the ACA and now teaches at the Harvard School of Public Health.

Conservative health care strategist Chris Jacobs, who worked for Republicans on Capitol Hill, said a new repeal-and-replace effort might not happen even if Republicans are successful Tuesday.

“Republicans, if they maintain the majority in the House, will have a margin of a half dozen seats — if they are lucky,” he said. That likely would not allow the party to push through another controversial effort to change the law. Currently there are 42 more Republicans than Democrats in the House. Even so, the GOP barely got its health bill passed out of the House in 2017.

And political strategists say that, when the dust clears after voting, the numbers in the Senate may not be much different so change could be hard there too. Republicans, even with a small majority last year, could not pass a repeal bill there.

2. Medicaid expansion

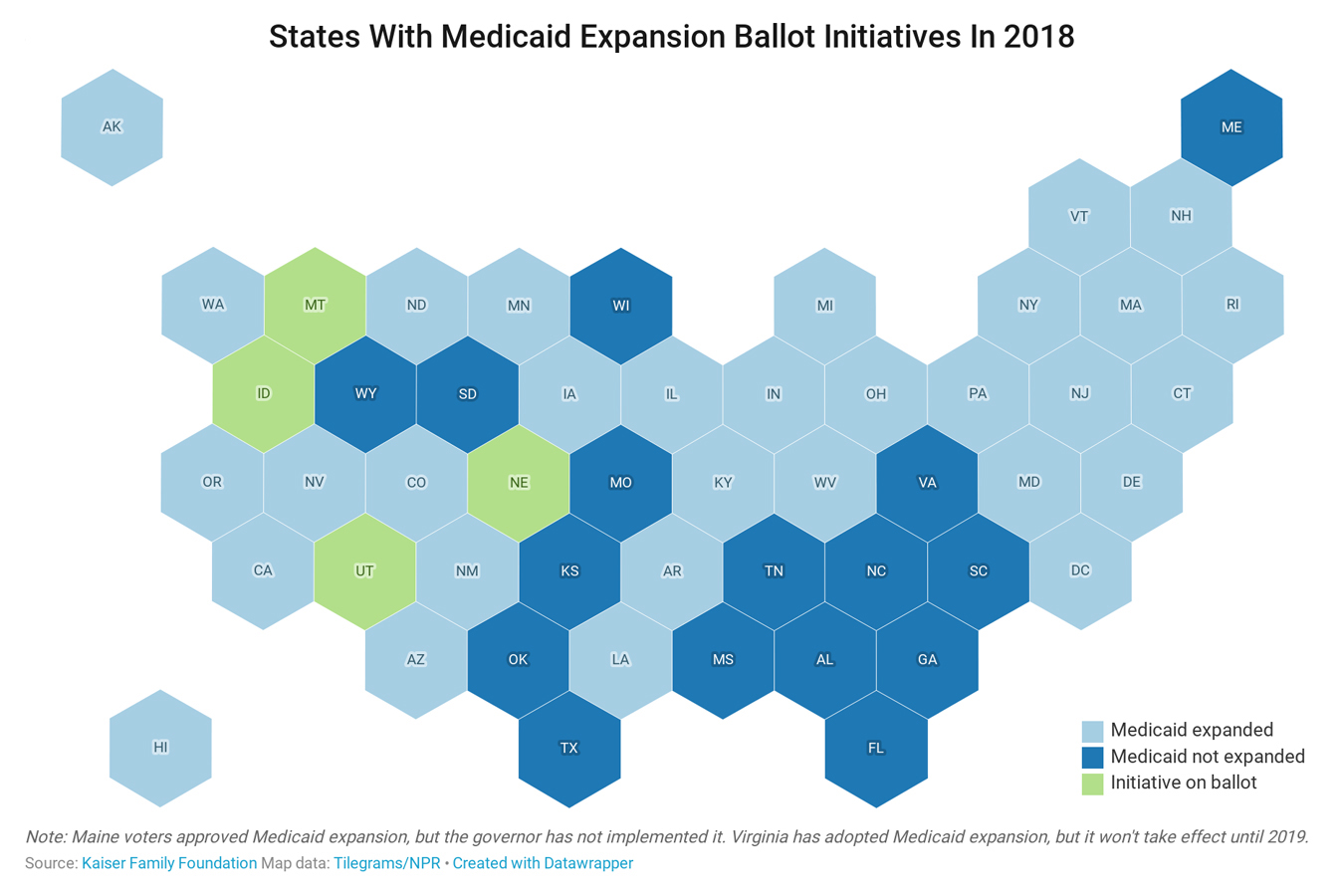

The Supreme Court in 2012 made optional the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid to cover all low-income Americans up to 138 percent of the poverty line ($16,753 for an individual in 2018). Most states have now expanded, particularly since the federal government is paying the vast majority of the cost: 94 percent in 2018, gradually dropping to 90 percent in 2020.

Still, 17 states, all with GOP governors or state legislatures (or both), have yet to expand Medicaid.

McDonough is confident that’s about to change. “I’m wondering if we’re on the cusp of a Medicaid wave,” he said.

Four states — Nebraska, Idaho, Utah and Montana — have Medicaid expansion questions on their ballots. All but Montana have yet to expand the program. Montana’s question would eliminate the 2019 sunset date included in its expansion in 2016. But it will be interesting to watch results because the measure has run into big-pocketed opposition: the tobacco industry. The initiative would increase taxes on cigarettes and other tobacco products to fund the state’s increased Medicaid costs.

In Idaho, the ballot measure is being embraced by a number of Republican leaders. GOP Gov. Butch Otter, who is retiring after three terms, endorsed it Tuesday.

But the issue is in play in other states, too. Several non-expansion states have close or closer-than-expected races for governor where the Democrat has made Medicaid expansion a priority.

In Florida, one of the largest states not to have expanded Medicaid, the Republican candidate for governor, former U.S. Rep. Ron DeSantis, opposes expansion. His Democratic opponent, Tallahassee Mayor Andrew Gillum, supports it.

In Georgia, the gubernatorial candidates, Democrat Stacey Abrams and Republican Brian Kemp, also are on opposite sides of the Medicaid expansion debate.

However, the legislatures in both states have opposed the expansion, and it’s not clear if they would be swayed by arguments from a new governor.

3. Medicare

Until recently, Republicans have remained relatively quiet about efforts to change the popular Medicare program for seniors and people with disabilities.

Their new talking point is that proposals to expand the program — such as the often touted “Medicare-for-all,” which an increasing number of Democrats are embracing — could threaten the existing program.

“Medicare is at significant risk of being cut if Democrats take over the House,” Rep. Greg Gianforte (R-Mont.) told the Lee Montana Newspapers. “Medicare-for-all is Medicare for none. It will gut Medicare, end the VA as we know it, and force Montana seniors to the back of the line.”

Gianforte’s Democratic opponent, Kathleen Williams, is proposing another idea popular with Democrats: allowing people age 55 and over to “buy into” Medicare coverage. That race, too, is very tight.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, congressional Republicans are more concerned with how Medicare and other large government social programs are threatening the budget.

“Sooner or later we are going to run out of other people’s money,” said Chris Jacobs.

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell suggested in an Oct. 16 interview with Bloomberg News that entitlement programs like Medicare are “the real driver of the debt by any objective standard,” but that bipartisan cooperation will be needed to address that problem

Republican Jacobs and Democrat McDonough think that’s unlikely any time soon.

“Why would Democrats give that up as an issue heading into 2020?” asked McDonough, especially because Republicans in recent years have been proposing deep cuts to the Medicare program.

Agreed Jacobs, “Trump may not want that to be the centerpiece of a re-election campaign.”