Medical device safety researchers are calling on the Food and Drug Administration to release hundreds of thousands of hidden injury and malfunction reports related to about 100 medical devices.

A recent Kaiser Health News investigation revealed that the FDA granted device makers numerous “exemptions” from the standard rules of publicly reporting harm related to devices.

One such program began about 19 years ago and allowed companies to file alternative summary reports about injuries or malfunctions into a database not visible to doctors, medical researchers or the public.

While the FDA pledged quickly to review the safety of one such device — the surgical stapler — researchers say the agency needs to open the data on scores of other devices, which have included mechanical ventilators and pacemaker electrodes.

“The FDA absolutely should be making all of this information available,” said Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Center for Health Research, who has testified to Congress and the FDA about device safety.

During a recent interview, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb said that he had no immediate plans to release the device-safety reports, but that the matter is under review. In an updated statement Tuesday, he added that “we are looking at ways to make ASR [alternative summary reporting] data received prior to 2017 more easily accessible.”

“I think that the imperative of the agency is to make as much of this information available to the public as possible,” Gottlieb said during the interview last week. “I think these databases by and large should be searchable to the public.”

An agency spokeswoman said the FDA revoked most of the “alternative summary reporting” exemptions in mid-2017 and asked device makers who kept their exemptions to file a public report summarizing what information they’d send in a spreadsheet directly to the agency. That new approach doesn’t affect the hidden reports dating to 2000.

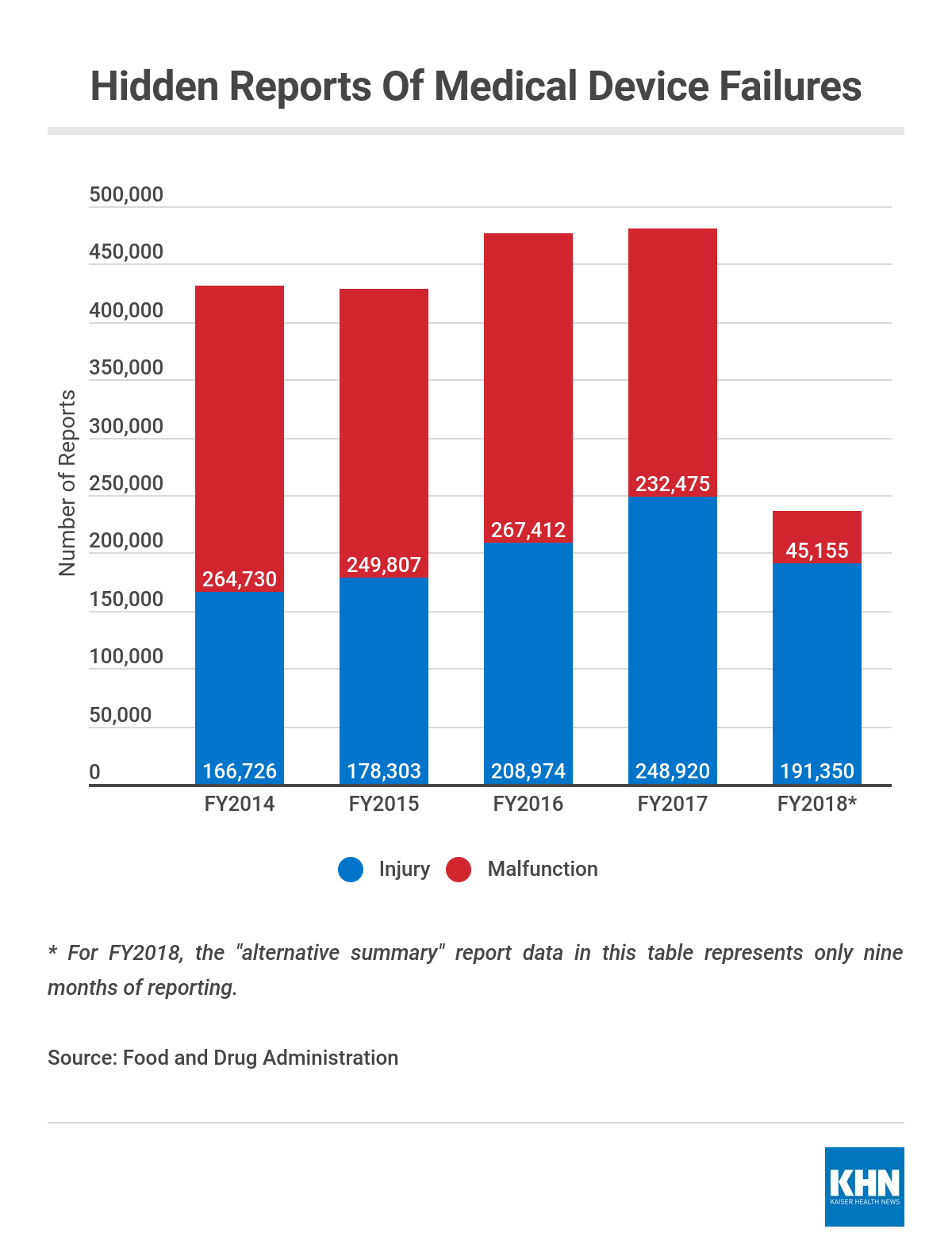

Agency data show that more than 2 million alternative summary reports have been filed since the start of 2014.

In a February guidance statement for device makers, the FDA said summary reporting can streamline reporting for the industry and simplify the agency’s review process “while maintaining or enhancing the quality, utility, and clarity of MDRs [device reports] through a more holistic view of reportable event trends.”

Makers of about 100 devices filed reports that way over the years, and the FDA has not disclosed the reports’ content beyond responding to KHN’s questions about specific devices. Among the devices involved are implantable defibrillators and the staplers, which in 2016 were linked to under 100 public reports of harm, even as nearly 10,000 malfunction reports were filed discreetly within the FDA.

Asked for more detail on staplers and other devices with exemptions, the agency referred to the Freedom of Information Act process, which can take nearly two years.

That’s not soon enough for organizations like the ECRI Institute. Chief policy officer Ronni Solomon said the nonprofit does device-safety analyses for the government and evidence-based reports for hospitals and performs device-related accident investigations.

Having thorough data on device-related harm is key on all fronts, she said, noting that the organization is exploring ways to get access to more FDA data.

Dr. Alan Shapiro, an associate professor at the New York University School of Medicine who has used the agency’s public device-safety database, called MAUDE, in his research, said paring down patient-safety data and keeping it in-house is the wrong move in the current era of artificial intelligence and automation.

He noted that an important safety tenet in hospitals is: the more eyes on the patient the better. He said there’s a clear parallel to the work researchers do with agency data to identify device-safety lapses.

“The FDA isn’t so capable that they can afford to hide data,” he said.

Hani Elias, chief executive of Lumere, said his consulting company uses the open FDA device data to advise health systems across the nation on device safety for purchasing decisions. He co-founded the company after seeing hospitals make device-buying decisions based on the effectiveness of the sales force rather than on quality and safety.

“There’s a lot of benefit in opening up this data,” Elias said.

Among the benefits of greater transparency would be the peer pressure among device makers — stripped of reporting exemptions — to make their products safer.

“You don’t want to be the people known for the products known for hurting people,” said Alan Card, an assistant professor and patient-safety researcher at the University of California-San Diego School of Medicine.

In 2018, the FDA approved a new pathway for makers of 5,600 device types to file malfunction reports in summary format. That program relieves the device makers of seeking a special exemption. It requires one public report detailing a novel or unique type of malfunction. Information about subsequent, similar malfunctions can be sent straight to the FDA in a spreadsheet.

The agency has also quietly granted device makers other summary-reporting exemptions for injury information gleaned from litigation and from device-specific registries used for research. Device makers filing such reports also have to file a public report summarizing the data that is sent directly to the FDA and isn’t readily available to the public.

Agency records show that some cardiac device makers have filed hundreds of death reports under the registry exemption. The FDA confirmed that nearly 12,000 litigation summary reports related to injuries associated with pelvic mesh were filed in 2017 alone.

Prior to the KHN investigation, Zuckerman said she was aware the FDA granted reporting exemptions but the sheer number of reports “takes my breath away.”

In the interview, Gottlieb said he “wasn’t aware of the full scope of the reports that weren’t going into MAUDE.” Gottlieb has announced his resignation; his last day will be April 5.

Card also said the KHN report was a surprise, but now that it’s out, it’s time for the FDA to open the records to help doctors and patients make the safest choices. “There are a lot of people out there who are trying to make reasonable decisions on data that isn’t what it was purported to be,” he said.