SANTA CRUZ, Calif. — For more than 30 years, public health officials and nonprofits in California have provided clean hypodermic needles to people who use them to inject drugs.

For nearly that entire time, opponents have accused the free needle programs of promoting drug use and homelessness.

But recently, opponents have deployed a novel strategy to shut them down: using environmental regulations to sue over needle waste. They argue that contaminated needles pollute parks and waterways — and their lawsuits have succeeded across the state.

A bill signed Monday by Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom will thwart that tactic.

Environmental challenges have already forced free needle programs in Orange County, Chico and Eureka to close or modify their operations.

The new law comes at a critical moment for a program in Santa Cruz. A final court ruling that could determine the fate of the program is expected within days, and it’s not clear how the law will affect the judge’s decision.

“We’re in the midst of an opioid crisis,” said Assembly member Joaquin Arambula (D-Fresno), a physician who wrote the bill Newsom signed, AB 1344. “We need all the tools that we have available for us to address this crisis head-on.”

Despite the legislative victory, lawsuits to challenge needle programs on other grounds are still possible, and local ordinances banning needle exchanges have flourished across California.

Under the new law, which takes effect Jan. 1, opponents of free needle programs will no longer be able to sue over violations of the California Environmental Quality Act, known as CEQA.

CEQA requires projects that need approval from a public agency or receive public funding to be assessed for their potential environmental impacts. This requirement applies to major construction projects, like reservoirs and freeway overpasses, and localized ones such as affordable housing. CEQA is enforced by lawsuits and has been invoked over the years to stop or slow unpopular proposals, like homeless shelters.

California allows licensed physicians to give clean needles to patients without authorization. Free needle programs run by local governments or community groups must be approved by the state, a county or city.

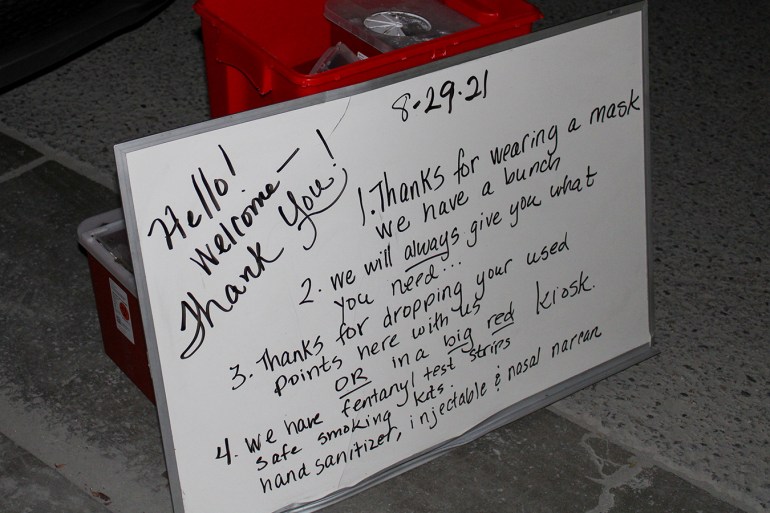

These programs, which allow people to dispose of used “rigs” and get new ones, attempt to reduce the spread of HIV and hepatitis C, which can spread among drug users who share needles, and decrease infections among users. Some are true “exchanges” that require people to turn in a used needle to get a new one. Others allow people to take what they need without returning them.

In the past few years, opponents have started focusing on the programs’ environmental impacts because some needles end up on the ground or in creeks and rivers.

Walt McNeill, a lawyer in Nevada City, California, challenged nonprofit-run needle programs in Chico, Eureka and Santa Cruz on behalf of local officials, former law enforcement officers and community groups.

McNeill said his clients aren’t opposed to needle programs in general, just ones they believe are run irresponsibly. “You have no idea where the needles are going, and no way of recovering needles effectively,” he said.

The trend in environmental challenges began a few years ago when the only needle program in Orange County shut down following a CEQA lawsuit. In 2020, a program created to address needle pollution in Chico closed after it settled a CEQA lawsuit, then later reopened on a smaller scale under a physician’s authority. Also in 2020, Eureka officials wouldn’t reauthorize a needle program after McNeill challenged it on environmental grounds.

Last year, McNeill sued one of two free needle programs in Santa Cruz County. Run by the Harm Reduction Coalition of Santa Cruz County, it operates out of a van and serves up to 75 people each Sunday on the same street corner in an industrial part of town. The complaint alleged the program “spread tens of thousands of used and unused hypodermic needle ‘litter’” throughout the community and has led to “environmental degradation of the creeks, streams, rivers and beaches.”

A superior court judge in Sacramento is expected to hand down her ruling soon. McNeill said he’s confident the judge will side with his clients despite the new law because of other flaws in the program. If she disagrees, he said, he may file another suit on other grounds.

“No matter how you slice it, the program will be deauthorized,” he said.

But Denise Elerick, founder of the coalition, said she believes her program will survive. She said arguments about needle litter mask anti-homeless sentiment.

“They say it’s about the environment but it’s not. They want people to die and disappear,” she said.

Decades of research shows that needle giveaways aren’t a major source of pollution, and that people who get needles from an exchange are more likely to dispose of them properly than those who don’t.

A 2019 study by Santa Cruz County’s Health Services Agency found that for every 10 needles that ended up on the ground or in a river, 1,000 made it into a sharps container, used to collect used needles, or an official disposal point. The report concluded that reducing needle litter would require more syringe programs and disposal sites, not fewer.

The Santa Cruz program, which began in 2018, gives out as many syringes as people request.

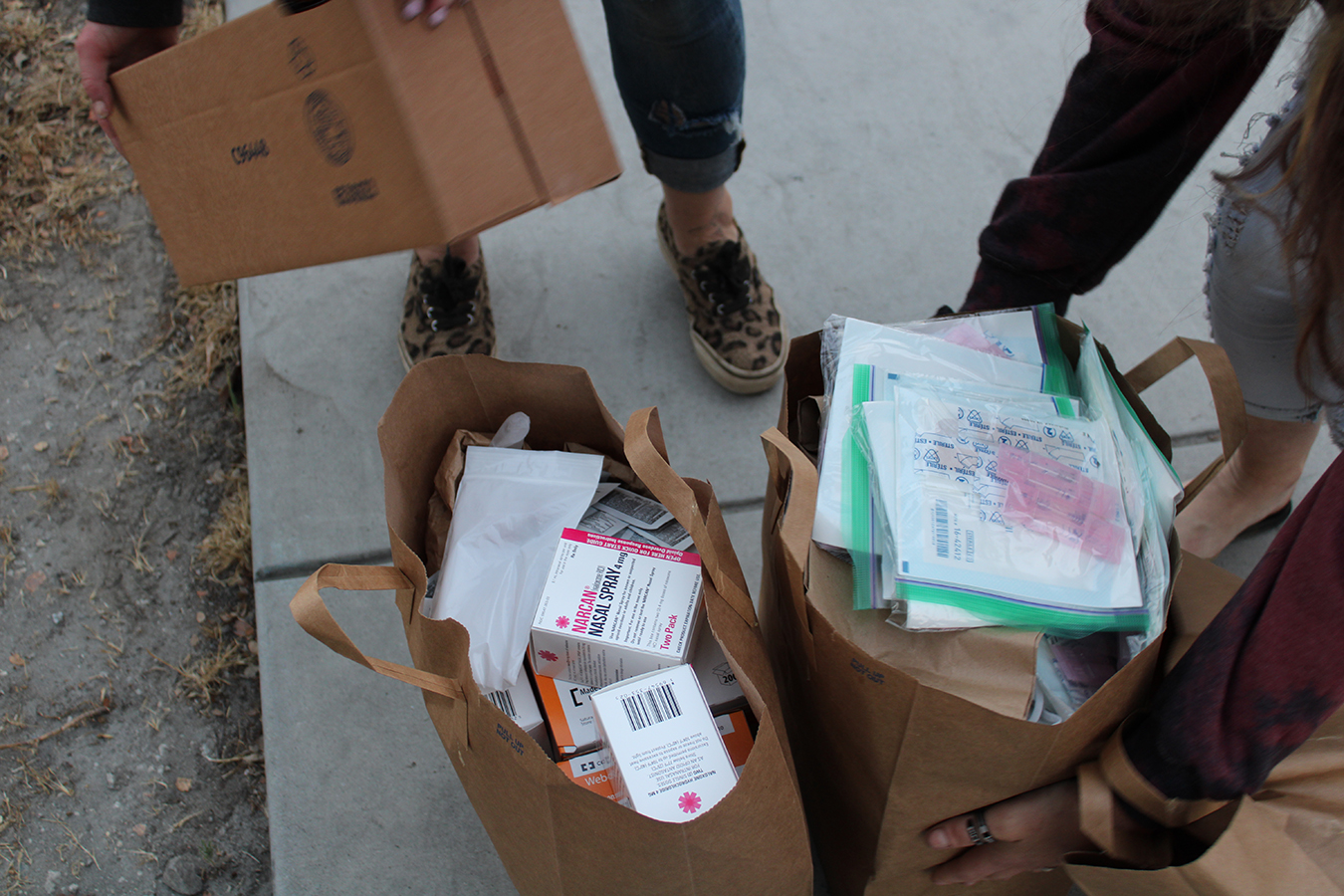

In addition to offering nine sizes of syringes, the program gives out sharps containers, ranging in capacity from a quarter gallon to 8 gallons, which can be returned, picked up or left at disposal kiosks around town.

On one Sunday in August, 56 people stopped by the van and 51 sharps containers were distributed. The coalition would not disclose how many needles it typically gives away.

The clients also gathered supplies to protect them from staph infections, covid and other dangers: condoms, hand sanitizer, masks, alcohol pads, drug-testing strips to ferret out fentanyl, and medication to reverse overdoses. The program even offered clean pipes to encourage that drugs be smoked — rather than injected — and reduce the spread of covid from sharing pipes.

Many who line up each week live in nearby parks and alongside creeks that are the focus of opponents’ environmental concerns. They said they have a vested interest in keeping the environment clean.

“Just because we’re drug addicts doesn’t mean we don’t take care of ourselves,” said one woman, 35. (In order to observe how the program works, KHN agreed not to name the people procuring supplies.) “Yeah, I live in a tent, but my tent is clean. I try to take care of other people and I take care of myself.”

The new law comes too late for programs like Chico’s, because the city has since passed an ordinance banning syringe exchanges. Similar bans have been adopted in Anaheim, Oroville, Butte County, Yuba City and elsewhere in the past few years.

Ryan Coonerty, a Santa Cruz County supervisor, said the county likely won’t adopt a ban, though he’s disappointed by Newsom’s decision. He believes the nonprofit needle program in Santa Cruz contributes to needle pollution more than the county-run program, which requires people to turn in used needles to get fresh ones.

“We will continue to struggle with needle litter and, unfortunately, not get any help from the state to stop needles from going into the ocean, parks and beaches,” he said.

But the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and other public health agencies say one-for-one programs limit the ways people can safely dispose of sharps, forcing them to hang onto their needles until the next needle exchange. That’s not realistic, according to the people who lined up to get needles from the Santa Cruz program.

“A lot of us are homeless,” said one 40-year-old woman, “and we can only stay someplace for so long.”

This story was produced by KHN, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.