Felicia Morrison is eager to find a health plan for next year that costs less than the one she has and covers more of the medical services she needs for her chronic autoimmune disease.

Morrison, a solo lawyer in Stockton, Calif., buys coverage for herself and her twin sons through Covered California, the state’s Affordable Care Act insurance marketplace. Morrison, 57, gets a federal subsidy to help pay for her coverage and she said that her monthly premium of $167 is manageable. But she spends thousands of dollars a year on deductibles, copayments and care not covered by her plan.

“I would just like to have health insurance for a change that feels like it’s worth it and covers your costs,” she said.

Her chances are looking up after lawmakers in Sacramento acted to enhance Covered California for 2020: They added state-funded tax credits to the federal ones that help people pay for coverage. And they reinstated a requirement for residents to have coverage or pay a penalty — an effort to ensure that enough healthy people stay in the insurance pools to offset the financial burden of customers with expensive medical problems.

An added benefit of these new policies: They appeal to insurers, which are expanding operations in the state, enhancing competition and offering consumers more choices.

California’s ACA exchange is not the only one benefiting from the renewed interest of insurance companies. Other states are expected to see more insurers enter or re-enter their marketplaces next year. That’s a critical signal, experts said, that the state-based marketplaces, which cover about 11 million people nationally, are becoming more robust and less risky for insurers — despite ongoing political and legal battles over the ACA.

“It’s taken longer than expected, due in part to the political rancor, but things seem poised to go well for next year,” said Katherine Hempstead, a senior policy adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. “The ACA market is becoming a better place for insurers and consumers.”

Hempstead said 2020 would likely be the second year in a row with a net increase in the number of insurers participating and relatively modest premium increases nationwide.

Covered California said last month it expected an average premium increase of just 0.8% in 2020, far below this year’s hike of nearly 9% and the lowest since the agency began enrolling people in October 2013.

Peter Lee, Covered California’s executive director, attributed next year’s slender rate increase to the new state-funded premium subsidies and the requirement that people be insured.

California is one of a handful of states offering its own subsidies to residents — and the first to provide them to people making more than the federal income threshold of 400% of the federal poverty level. The subsidies are available to people earning up to 600% of the poverty level, which are individuals making up to about $75,000 a year and families of four with an annual income up to $154,500. The extra aid is expected to help 235,000 families who didn’t previously qualify for federal help.

California insurers have responded enthusiastically.

Anthem Blue Cross, which withdrew from most of the state’s individual market in 2018, is jumping back in. It will expand offerings in the Central Valley and return to the Central Coast, Los Angeles County and the Inland Empire. Anthem health plans will be available to nearly 60% of Californians next year, according to Covered California.

Blue Shield of California will also expand its HMO plan into parts of Tulare and Riverside counties and add coverage in Kings and Fresno counties. And the Chinese Community Health Plan will expand to cover all of San Mateo County next year.

“Nearly every Californian will be able to choose from two carriers, and 87% will have three or more choices in 2020,” said Lee. He urged people to shop among plans, including the new ones, to try and lower their premiums.

“I definitely plan to look carefully at all new options,” Morrison said.

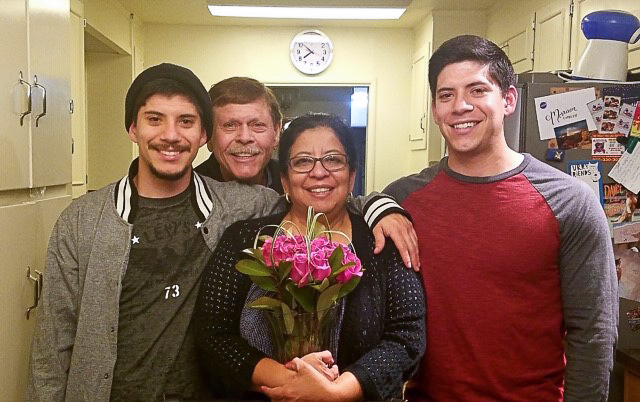

Felicia Morrison, pictured with her husband, Bryant, and sons, Neil and Nathan, buys coverage for herself and her sons through Covered California. (Courtesy of Felicia Morrison)

Anthem, the nation’s second-largest health insurer with 40 million enrollees in 10 states, also plans to expand its ACA coverage in Virginia next year.

Centene, which has 12 million enrollees nationwide, plans to expand into new ACA markets next year as well, a company spokesperson said. It operates in 20 states, three of which it entered for the first time this year.

Two startup insurers, launched in recent years in part to serve the ACA marketplaces, also plan expansions in 2020. Bright Health, based in Minneapolis, announced in late July that it will offer ACA plans in six more states, on top of the four it now serves.

And New York-based insurer Oscar, which this year offered ACA plans in nine states, including California, plans to enter Colorado, Pennsylvania and Virginia, as well as new areas of New York and Texas.

Participation rates matter. A 2017 study by researchers at the Urban Institute found that the median monthly ACA premium that year was $451 in areas with one insurer compared with just over $300 in markets with three to five insurers and $270 in those with six or more insurers.

The number of insurance companies offering plans in ACA marketplaces has fluctuated. From 2014 to 2016, the average number was between five and six, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. That number declined to 3.5 last year, following Republican threats to gut or replace the ACA and Trump administration changes to the marketplaces. (Kaiser Health News is an independent program of the foundation.)

Premiums in some areas rose 20% to 30%.

This year, the average number of plans ticked up to four.

But variability among states is still substantial. Four states — Alaska, Delaware, Mississippi and Wyoming — have just one ACA insurer this year. In contrast, seven states — California, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Texas and Wisconsin – have eight insurers or more.

“Anything less than three is not a good situation,” said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at the Center on Health Insurance Reforms at Georgetown University in Washington. “It looks like the marketplaces are stabilizing, though, and importantly the insurers are now making more money in this market.”

Kelley Turek, the director of commercial insurance at America’s Health Insurance Plans, the main trade group for health insurance companies, agreed. “The churn is finally slowing down,” Turek said. “Companies are staying and expanding into new geographical areas. We strongly agree the market works best when consumers have more choice.”

The ACA marketplaces still need more regulatory predictability, however, and political divisiveness over the ACA continues to undermine that, Turek said.