This story was updated Feb. 18 to reflect that Michael Bloomberg will be among Democratic presidential candidates participating in this week’s primary debate.

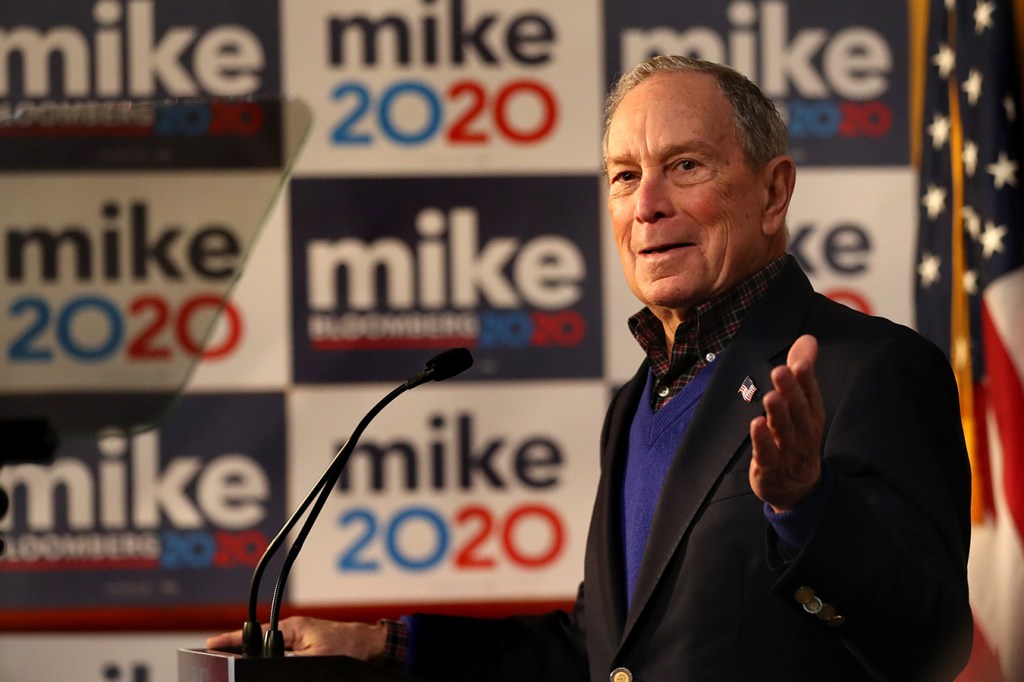

Former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has spent more than $200 million arguing that he should be the Democratic nominee for president, blanketing the airwaves with advertisements.

One of those ads emphasizes health care — leaning into the characterization of Bloomberg as a moderate Democrat with experience getting results. It offers an impressive list of statistics and accomplishments.

And, because of a strong showing in a national NPR/PBS NewsHour/Marist Poll, he has qualified to join five other Democratic presidential candidates Wednesday on the Las Vegas debate stage.

“Mayor Bloomberg helped lower the uninsured by 40%, covering 700,000 more New Yorkers,” says a New York-based nurse featured in the commercial. “Life expectancy increased. He helped expand health coverage to 200,000 more kids and upgraded pediatric care. Infant mortality rates dropped to record lows. And as mayor, Mike Bloomberg always championed reproductive health for women.”

Are those numbers accurate? And if so, how much credit does Bloomberg deserve? Most important ― what can his record tell us about how he might approach health care from the Oval Office? These questions seemed important in advance of Wednesday’s primary debate.

The New York Record

Bloomberg’s campaign directed us to independent estimates by the U.S. Census Bureau, which tracked New York City’s uninsured rates during Bloomberg’s time as mayor, which spanned 11 years from 2002 to 2013.

The numbers check out. The city’s uninsured population dropped from 1.8 million in 2001 to 1.05 million in 2013. Life expectancy did go up. And the number of kids without coverage fell from about 270,000 to 67,900.

Data from the city’s health department suggests that the infant mortality rate also dropped substantially ― from 2001’s 6.1 deaths per 1,000 live births to 4.6 deaths in 2013. That decline was ahead of national trends. During the same period, the national infant mortality rate dropped from 6.85 per 1,000 live births to 5.86.

Bloomberg’s campaign pointed to local efforts promoted by the then-mayor ― for instance, offering online help for uninsured people to find coverage, making it easier to distribute pamphlets marketing different coverage options, home visits for newborns and mothers from health department-employed nurses, and a city-funded program in which community organizations used case management and peer education to combat infant mortality.

But others questioned how meaningful those initiatives were in driving the city’s health insurance gains ― and, more broadly, how great a role Bloomberg played.

“Every single thing ― the 700,000, and the 200,000, all of that ― is directly related to state policy changes,” Elisabeth Benjamin, vice president of health initiatives for Community Service Society, an anti-poverty advocacy group in New York City, said about the improvements in the city’s uninsured rates.

Specifically, Benjamin pointed to efforts by then-Gov. Eliot Spitzer to expand eligibility for the Children’s Health Insurance Program. That, she said, drove most of the gains for kids’ coverage.

The state also expanded Medicaid eligibility, which helped more adults get coverage during Bloomberg’s administration, noted Sherry Glied, a health economist and dean at New York University.

She gave Bloomberg more credit than Benjamin did, citing city efforts to advertise the program and sign people up: “The city couldn’t have done it without the state, but the city played a role,” Glied said.

As for life expectancy ― that’s tricky. Bloomberg gained national attention for efforts to restrict tobacco and soda, for instance. But while people were expected to live longer under Bloomberg’s tenure, it’s unclear that change had anything to do with his work on insurance or public health.

For one thing, Glied noted, there was a particularly large influx of people moving to New York City during that time. Many of them were likelier healthier to begin with. And, big picture, it’s methodologically difficult to figure out why people’s outcomes improved.

“It’s hard to parse this,” she said. “This is the happy moment where everything goes in the right direction, but this is not a randomized experiment. There was no control New York City.”

So the numbers Bloomberg points to are correct. But it’s difficult to say how much responsibility he had for those improvements, and how much was due to external factors.

Bloomberg, The Candidate

What does all this mean when looking at Bloomberg’s 2020 campaign?

His health care agenda places him firmly among the Democrats’ moderate wing. He talks about building on the Affordable Care Act ― largely by expanding subsidies for people buying private insurance, and capping what they will pay out-of-pocket ― as well as creating a government-run public option for coverage that people can buy into. He has also said he would work to eliminate surprise medical billing and empower Medicare, which insures older Americans, to lower drug prices.

That plan isn’t much different from those put forth by former Vice President Joe Biden or former South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg. But Bloomberg is suggesting that his record in New York better equips him to deliver.

“He’s pointing to his record as mayor, where he did make health care a priority, as evidence that this is an issue that’s important to him,” said Sara Collins, a vice president at the Commonwealth Fund in New York.

Would that record translate to the White House? A comparison is difficult to make because the circumstances would be dramatically different.

As mayor, Bloomberg worked against a backdrop in which state lawmakers also wanted to expand coverage, and extended resources to promote that effort. That’s no sure bet in Washington, where the Affordable Care Act has remained a political punching bag for Republicans, a party that political analysts suggest has a good chance of holding onto the Senate in 2020. In that environment, building on the ACA would be much harder than it was to expand coverage in New York.

There are other areas to consider, though. In New York, Bloomberg gained national attention for efforts to tamp down on smoking, address diabetes and bolster access to reproductive health. Those are areas where a president’s influence can matter.

“His record suggests that he sees the public health ― tobacco, salt, calories, all of that stuff ― as a pretty significant component of what happens to people’s health, and also as an appropriate place for the government to take action,” Collins said. “It’s not hard to imagine where he’d be on Juul.”