A significant portion of previously uninsured Californians gained medical coverage through the nation’s health care law – about six in 10 during the state’s first open enrollment, according to a survey released Wednesday.

All told, about 3.4 million people who didn’t have health insurance before sign-ups began last fall are now covered, according to the survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation. (Kaiser Health News is an editorially independent program of the foundation.)

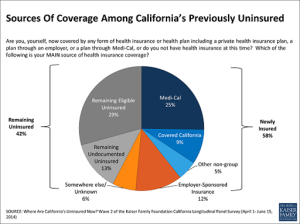

The largest share of the previously uninsured — 25 percent — enrolled through the state’s Medi-Cal program, which has long covered poor families but was expanded this year to include adults without children. Nine percent purchased private plans through the subsidized insurance marketplace, Covered California, which opened in October. And 12 percent became insured through their jobs, the researchers found.

Sara Rosenbaum, health law professor at George Washington University, said the state’s progress has national importance.

“California is such an outsized presence in terms of uninsured people,” she said. “For California to have made this progress has a major effect on the national uninsured numbers.”

About 1.4 million people purchased private plans through the insurance marketplace by the end of open enrollment – far more than any other state, according to Covered California. Nearly 2 million had enrolled in Medi-Cal.

Allynne Noelle, a principal dancer for the Los Angeles ballet, chose a Blue Shield plan offered by her employer through Covered California’s small business exchange. And although the $5,000 deductible is “extremely high” for her, she’s relieved, she said.

“This new coverage is a peace of mind,” she said. “It will save me from drowning in medical bills.”

The number of previously uninsured Californians cited by the survey who have gained coverage is much larger than expected, said Gerald Kominski, director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research, which helped create the official enrollment projections for Covered California.

“If the numbers are accurate and borne out by larger studies … I think it is an indication that the law is working even better than many of us anticipated,” he said.

Still Uninsured

Even though the state exceeded its own expectations for coverage, more than 40 percent of those previously uninsured still don’t have health insurance, according to the survey. Some said they didn’t enroll because of the cost, while others feared that signing up would bring attention to their family’s immigration status. Those who are in the U.S. illegally are not eligible for coverage.

The remaining uninsured may be hard to reach. More than 80 percent either have never been covered or haven’t had a plan in at least two years, the survey found. About 60 percent are Latino.

“It would be nice to have coverage,” said Steve Mercill, 59, who most of his life has worked jobs that didn’t offer coverage. He is now a paid caregiver for his father, a retired doctor, in a small town near the Oregon border.

Mercill tried to purchase a plan through Covered California last year but said he couldn’t get the website to work and couldn’t get the help he needed through the call center. He plans to try again in the fall.

The Kaiser Family Foundation survey focused on those without coverage last fall, before open enrollment.

Kominski of UCLA said that by focusing only on those who were previously uninsured, the survey doesn’t paint a complete picture: While some people gained coverage, others lost it.

“There is churn in the health care system and this study does not account for that,” he said.

Aggressive Enrollment

Before the nation’s health law took effect, California had the highest number of uninsured in the nation, coming from highly diverse ethnic backgrounds and cultures. But the state embraced Obamacare before most others and was the first to create a state-run insurance exchange.

Though there were some initial technical problems in the enrollment process, they were fewer and less severe than those in the federal exchange and other states. In addition, the hospitals, community clinics and social services offices were aggressive in enrolling those eligible for Medi-Cal.

“The fact that a quarter of the previously uninsured Californians ended up enrolled in Medi-Cal points to what a key piece Medicaid is in the puzzle in getting more Americans covered,” said Mollyann Brodie, executive director of the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Public Opinion and Survey Research.

“That was a piece that often got less attention during open enrollment season,” she said.

Most of those who got covered said it was easy to sign up. Leslie Ziegler, 31, said signing up for insurance through the Covered California website only took about an hour. Before Obamacare, Ziegler, a San Francisco high-tech entrepreneur, had been turned down by several insurance companies because she had ulcerative colitis, a chronic disease that requires costly medication and treatment.

Companies can no longer deny coverage because of pre-existing conditions. Ziegler is thankful, saying having access to insurance and health care whenever she needs it is “a wonderful thing.”

Some respondents said, however, that it was difficult to confirm their coverage. Even now, hundreds of thousands of Medi-Cal applicants are waiting for cards confirming their eligibility.

Teresa Martinez sought help at a Los Angeles health clinic to sign up for Medi-Cal, but months later, she is still waiting for her card. Martinez, a Koreatown hair stylist, said she is anxious to see a doctor to treat arthritis and pain in her leg, as well as help her keep her blood sugar in check to fend off diabetes.

“It seems like I am just hitting closed doors,” she said last week. “I don’t know what’s up.”

‘A Huge Relief’

Despite an early lag in Latino enrollment, the survey found that more than half of previously uninsured Latinos ultimately got coverage.

“It’s a huge relief,” said Newport Beach restaurateur Sandra Lopez, a 41-year-old Mexican immigrant who enrolled her family, including a young adult son with epilepsy, in a subsidized private plan through California’s exchange.

The state’s far-reaching efforts to spread the word about the law and get people signed up made a difference, researchers said. About 60 percent of Medi-Cal or Covered California enrollees had someone help them sign up. About seven in ten uninsured Californians who were contacted about signing up did so, compared to about half of people who were not contacted.

“Outreach was such an important predictor in whether an uninsured person got health insurance or not,” Brodie said. But friends and family did not have much of an impact on whether people enrolled.

Meifeng Lui, 52, said her family of five had been uninsured for four years because they could not afford coverage. Lui said she was “very grateful and so blessed” that the enrollment counselors spoke their language at the Chinese Community Health Plan in San Francisco and helped her enroll in a private plan through Covered California.

“I was so happy because someone knew what to do,” said Lui.

When Maria Garcia decided to enroll under Obamacare, she sought help from a counselor at the Ravenswood Family Health Center near her home in East Palo Alto.

She didn’t feel comfortable navigating Covered California’s site. Within hours, she said, the counselor helped her settle on a Kaiser Permanente plan, for which she’d pay just $36 a month thanks to a subsidy from the state.

According to the survey, most of those who got insurance said their plan is “a good value” for what they pay but nearly half of people who got plans other than Medi-Cal said that it has been difficult to afford the coverage.

Researchers found stark differences in how people signed up for Medi-Cal versus the subsidized private plans in Covered California. More than half of Medi-Cal recipients enrolled in person, compared to 15 percent over the Internet. More than half of Covered California enrollees, however, signed up over the Internet, compared to 15 percent in person.

The researchers surveyed 2,001 uninsured Californians last summer, then conducted a second round of interviews with many of the same people this spring. The margin of sampling error was plus or minus 4 percentage points. For subgroups sampled, the margins were slightly larger.

Sarah Varney, Daniela Hernandez and Heidi de Marco contributed reporting.