John Minor of Manhattan Beach epitomized the active Californian. The retired psychologist was a distance runner, a cyclist and an avid outdoorsman, says his daughter Jackie Minor of San Mateo.

“He and my mom were both members of the Sierra Club,” Jackie said. “They went on tons of backpacking trips — climbing mountains and trekking through the desert. He was just a very active person.”

But in September 2014, he fell ill with terminal pulmonary fibrosis — a lung disease that his family says slowly eroded his quality of life.

Two years after that diagnosis, last September 15, John Minor, surrounded by his family, sipped his last drink: apple juice laced with a lethal dose of medication his doctor had prescribed for him. He was 80.

“He laid down and went to sleep and he was in a coma for about two hours and then he passed,” Jackie said. “It was very peaceful.”

Since California’s End of Life Option Act law took effect a year ago on June 9, 2016 at least 500 Californians have received life-ending prescriptions, according to data collected by Compassion & Choices, an advocacy group for aid-in-dying laws nationwide. (The State of California is scheduled to release its official accounting on or before July 1.)

The organization reports that nearly 500 hospitals and health systems and more than 100 hospice organizations allow aid-in-dying to be offered to their patients and 80 percent of insurers statewide cover expenses related to it. The California law created a process for dying patients to ask their doctors for a lethal prescription that they can then take privately, at home.

“What the numbers are showing is that the law is working incredibly well,” said Matt Whitaker, the organization’s point person for California and Oregon which both have aid-in-dying laws. “That it’s working as the lawmakers intended.”

Still, for some patients, finding a doctor willing to prescribe the life-ending drugs can be difficult, in part because the law allows doctors to opt out of prescribing – even when the hospital where they work has agreed to participate in assisting patients.

“It’s a very nuanced decision,” said Dr. Elizabeth Dzeng, an assistant professor of hospital medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, where, she estimates, about three dozen patients have made the request so far.

Dzeng said the decision to prescribe doesn’t come easy for many doctors.

“Even if they’re in support of aid-in-dying they don’t necessarily want to be the person identified as the go-to person for aid-in-dying because that’s a very different implication,” she said.

Dr. Stephanie Harman, medical director of palliative care services for Stanford Health Care, has taken a deep dive into the issue at Stanford. In a recently published paper, she and her co-author reported that 6 of the 13 patients had taken the medicine to end their lives. Harman said about half of those 13 patients couldn’t get the lethal drugs from their own doctor.

One reason, she said: “There is a certain stigma for being known as a physician who writes these prescriptions. There is in the field, in medicine, a question of whether this is an ethical act for a physician.”

Other hospitals and health systems statewide are also trying to get a sense of what their terminally ill patients are experiencing. At UCLA, about 20 patients so far have received prescriptions – but only about half of them have gone on to take the meds, said Dr. Neil Wenger, a professor of medicine at UCLA and director of the UCLA Health Ethics Center.

Wenger has helped develop the UCLA protocol that guides doctors through the requirements of administering the medication to qualified patients.

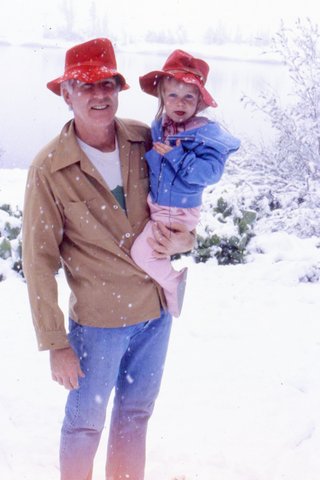

John Minor with daughter Jackie Minor on July 4, 1982, in Virginia Lakes, Calif. Jackie calls her dad’s death last September “very peaceful.” (Courtesy of the Minor family)

Among the physicians he’s spoken with, there is a “whole range of preferences” regarding how and whether to participate in the process.

A “relatively small number” oppose the law, he said. Many others, however, believe patients should have access to aid-in-dying but don’t want to be involved themselves. Complying with the law is not easy; doctors must ensure that the patient is likely to die within six months, mentally competent to make an informed decision and physically able to take the medicine. A second doctor has to agree. Patients must make two oral requests at least 15 days apart and a written request. And doctors have to document the whole process with various forms and paperwork along the way.

“It raises a lot of feelings on the part of the doctor,” he said. “It is something very, very different than what a doctor does — which is saving people. And it’s complicated. It takes a whole lot of time.”

Dr. Catherine S. Forest is one doctor who is committed to taking that time to assist patients who want the prescription.

She practices family medicine in the Stanford health system. Since the law passed, she’s assisted five patients who came to her after their own doctors refused.

Forest said what’s happening now in California is reminiscent of what happened in the 1970s, when abortion became legal. Even among doctors who agreed with Roe v. Wade, there was a reluctance to perform abortions.

“It takes a while for people to train, to feel comfortable and to provide. And that was because it was not legal and then it was legal — and there are very few instances where we do that in medicine,” she said.

Aid-in-dying is one of those challenging moments for doctors, she said. It will take time for California to catch up with other states, like Oregon, that have well-established training resources to help doctors learn the process.

Until that happens, some terminally ill patients who want a lethal prescription may find it challenging to get one. That’s what happened with John Minor.

After he learned his doctors would not prescribe, his family started scrambling.

“I started cold-calling … different hospitals and different departments within different hospitals,” said Jackie.

Ultimately, the family was able to enroll her father in a Kaiser Permanente plan where he received the prescription that he took last fall.

“Mentally he was ready,” said his widow, Sherry Minor. “It was an easy day for him.”

Kaiser Health News is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

This story is part of a partnership that includes NPR and Kaiser Health News.