Paula Wilson has seen some tough times in her 23 years as the CEO of Valley Community Healthcare, a clinic that provides care for the poor in North Hollywood, Calif. But nothing was quite like Nov. 9, the day after the U.S. elections, when walking around the office “was like coming into a funeral,” she said.

Her staff worried that a repeal of the Affordable Care Act, long promised by Republicans, would obliterate their jobs. Patients fretted it would jeopardize their care.

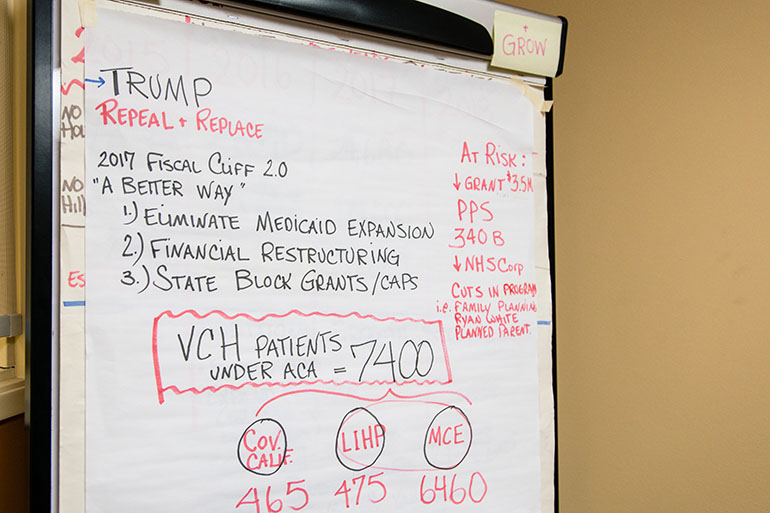

Nearly a third of the clinic’s 25,000 patients were newcomers, many of them recently covered through the expansion of Medi-Cal ushered in by the Affordable Care Act. Thanks to the expansion, Valley Community Healthcare had been growing rapidly, opening one new site, adding on to others, and offering patients new dental and mental health services.

What would happen if this new source of financial support were taken away?

Wilson didn’t have an answer that day, and she still doesn’t. But she’s hanging on to a cautious hope. “Pretty much that whole first week was getting a grip and assuring people: We’ve been here 46 years and we’re not going anywhere,” she said. “We’ve fought the fight before, and we’ll do it again.”

In the absence of details about the impact and timing of a possible ACA repeal, Wilson’s brand of determination is all community clinics can count on for now.

Republicans, newly empowered by Donald Trump’s ascendance to the White House, have made clear they plan to repeal large parts of the landmark health care law in short order. The timing of any replacement is still uncertain, though political pressure has been growing recently for any void left by a repeal to be quickly filled with a new plan. For the time being, however, consumers are unlikely to see big changes in their health care.

Community clinics are key providers of primary care services for the poor. CaliforniaHealth+ Advocates, which represents the state’s clinics, estimates that they serve 6.2 million Californians — an increase of more than a million in less than five years. Today, more than 3.5 million community clinic patients are covered by Medi-Cal, California’s version of Medicaid, the federal health insurance program for people with low incomes.

More than half of patients who signed up for Medi-Cal after the advent of the ACA have gotten their primary care at community clinics, according to a December 2015 report by the California Health Care Foundation. (California Healthline is an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.)

Historically supported by Democrats and Republicans alike, community clinics worked hard to implement Obamacare reforms, and they benefited as a result. Many, like Valley Community Healthcare, helped enroll patients and expanded their services, taking advantage of special ACA funding that enabled them to improve their facilities and systems of care.

The same scenario has played out nationwide at many of 1,400 federally backed community health centers — a type of community clinic — according to two studies published recently in the journal Health Affairs.

One of the studies, which used data from 2012 to 2015 to track visits to community health centers, showed that in states that adopted the Medicaid expansion, the centers saw more patient visits, including those for mental health treatment, and lower rates of uninsured patients — a financial boon for clinics that typically operate on thin margins.

The second study, which examined data from 2011 to 2014, found that in the Medicaid expansion states, patients were more likely to receive asthma treatment when it was needed, have their body mass index assessed, get pap smears and keep their blood pressure relatively stable.

Proponents of the health reform law in California had hoped the expansion of community clinics would provide primary care for more patients, thus reducing expensive emergency room visits at safety-net hospitals.

“Health centers have been the poster child of positively embracing the ACA. They’ve gone along with everything,” said Blue Shield of California Foundation CEO Peter Long, whose organization supports the clinics. But without clarity about where funding will come from in the future, or how much of it there will be, it’s possible that clinics will “go into hunker-down mode,” he added. That could mean limiting hours, reinstating waiting lists for new patients and cutting promising new programs.

Implementing Obamacare “put a lot of stress on their systems,” Long said. “To unwind it would be equally hard.”

Wilson and other clinic CEOs say they’re trying to anticipate worst-case scenarios and plan accordingly, but that’s hard when Congress hasn’t specified what changes it is planning, or when to expect them.

“Right now it’s all crystal ball gazing,” said Steven Wallace, associate director of the UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. “‘Repeal and replace’ is a great slogan, but ‘replace’ is really hard to figure out.”

Community clinic leaders say they’re focusing on several funding challenges. First is a potential rollback of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion program, which extended new coverage to about 20 million people in the U.S., including more than 5 million in California, said Carmela Castellano-Garcia, CEO of CaliforniaHealth+ Advocates.

Some also worry that shifting Medicaid to a block grant system, an idea President Trump has endorsed, would result in cuts to services; or that Congress could decline to reauthorize “330 funding” — an additional $5 billion community clinics receive each year from the federal government. That stream of federal dollars is set to expire in September 2017.

That funding, in addition to payments from the Medi-Cal expansion, allowed the Los Angeles Christian Health Centers to add medical, mental health, dental and case management staff and open two new sites.

The clinic, headquartered on Skid Row in downtown Los Angeles, also launched a fundraising campaign to revamp and enlarge its flagship facility. But CEO Dr. Lisa Abdishoo now worries that some financial assumptions made in planning the expansion may no longer apply now that Trump has been sworn in. “We’re trying not to panic, but now we have to question the sustainability of some of the growth,” she said.

Health care advocates have advised community clinics that they may need to “look at 2009 levels” to plan for post-ACA operations, Abdishoo said. That year, Los Angeles Christian Health Centers served 6,600 patients a year, compared to 10,000 today.

Jane Garcia, CEO of La Clínica De La Raza, a 32-site clinic network in Alameda, Contra Costa and Solano Counties, said her organization could lose ground on hard-fought cost reductions if people’s insurance is taken away and they revert to their old behavior of seeking care only when they are very sick.

“Patients who don’t have coverage hesitate to come in and see the doctor, and they hesitate to seek preventive care,” Garcia said. “That’s the kind of thing that was starting to have an impact on bending the curve on cost reduction.”

ACA-related grants allowed La Clínica’s health centers to improve case management and collaborate more effectively with partners such as Sutter Health, which also saved money by reducing the number of patients seeking primary care in emergency rooms. La Clínica would probably have to cut such administrative efforts were the ACA repealed, Garcia said.

Pamela Richardson, a 60-year-old patient of Valley Community Healthcare who suffers from an iron absorption disorder called hereditary hemochromatosis, was unable to get health insurance before Obamacare prohibited insurers from excluding people with preexisting medical conditions. The clinic helped her sign up for coverage through the Medi-Cal expansion.

Once Richardson was covered, she got long-delayed primary care, which revealed that she had “scary high” blood pressure and a lump in one breast (which proved benign). “When you don’t have insurance you don’t get breast exams. You don’t have pap smears,” she said. “I wish people had a little more patience with Obamacare. Once you get what’s wrong with you under control, the cost would come down.”

Lisa Zeelander, a doctor at Valley Community Healthcare, examines Richardson in December 2016. (Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Wilson, Castellano-Garcia and others said they plan to make precisely that case — that community clinics represent a good value — once state and federal officials begin mulling an ACA replacement in earnest.

A November 2016 study in the American Journal of Public Health showed that Medicaid spending was 24 percent lower for patients who received a majority of their primary care from federally qualified health centers — a type of community clinic — than for patients who got care in other settings. The savings extended across all services, the study’s authors reported.

In rural Shasta County, where a majority voted for Trump, one in three people has Medi-Cal coverage. Dean Germano, CEO of Shasta Community Health in Redding, said he has already launched conversations with staffers of Republican U.S. Rep. Doug LaMalfa, whom he considers “a friend of the health centers.”

“Our mission is to make people like him realize what [repeal] will mean for people on the ground,” Germano said. “If the system goes through a major shock, what would happen to jobs? It would have a major impact on rural communities.”

Another clinic CEO, Kim Wyard of Northeast Valley Health Corporation in San Fernando, said she takes heart because Congress will have to do something to replace what it is taking away. Just blowing everything up isn’t an option, she said.

“We need a safety net, and if more patients are uninsured, we’ll need it more,” Wyard said. “We’re cost-effective,” she added. “Our new president wrote ‘The Art of the Deal.’ He likes a deal. I don’t think there’s a better deal than health centers.”

Shefali Luthra contributed to this report.

This story was produced by Kaiser Health News, which publishes California Healthline, an editorially independent service of the California Health Care Foundation.