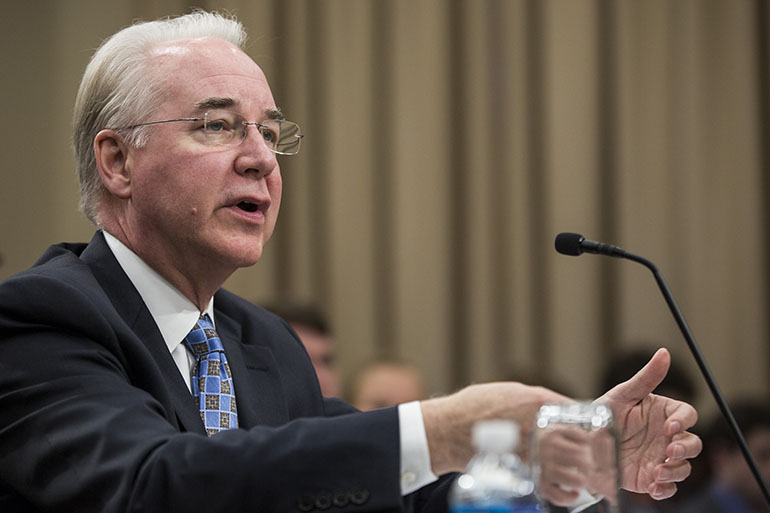

In back-to-back appearances on Capitol Hill Thursday, Health and Human Services Secretary Tom Price sparred with Democrats over the Trump administration’s budget cuts for his department and coming troubles in the individual health insurance market.

“President Trump’s budget does not confuse government spending with government success,” Price said, defending a spending plan that calls for substantial funding reductions to Medicaid, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health and other HHS agencies.

The problem with many federal programs “is not that they are too expensive or too underfunded. The real problem is that they do not work — they fail the very people they are meant to help,” Price said in testimony before the Senate Finance Committee and the House Ways and Means Committee.

He cited Medicaid, the federal-state insurance program for low-income people, as an example of where rising costs require reforms. The administration’s budget would reduce federal Medicaid funds to states by $610 billion over a decade. Under its proposal, states would gain latitude over how to spend those funds, which Price said would lead to innovations and efficiencies.

Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) questioned whether HHS is budgeting enough money under Medicaid to fight the opioid-abuse epidemic. Seventy percent of the $939 million that Ohio spent on opioid treatment in 2016 came from federal Medicaid dollars, he said.

“You would never propose we fight cancer with a $50 million increase to a grant program,” Brown said. “… How does this possibly work if you’re going to cut the biggest revenue stream to treat people?”

Price pushed back, pointing out that more than 52,000 Americans died of overdose deaths in 2015.

“We continue to tolerate a system that allows for overdose deaths, and I simply won’t allow it,” Price said.

Trump’s budget has come under heavy attack in Congress since its release last month and is expected to undergo much rewriting. The budget would take effect for the fiscal year starting Oct. 1.

Democratic senators and representatives on the committees repeatedly challenged Price on his testimony and the administration’s health care policies, sometimes using strong words and loud voices.

“It’s mean-spirited. It’s not good for America. We can do much better,” thundered Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.).

With insurers facing looming deadlines to decide whether to participate in the Affordable Care Act’s online marketplaces next year, lawmakers also pressed Price on whether the Trump administration will pay insurers about $7 billion in “cost-sharing subsidies” for 2018. The White House has sent mixed signals, but many insurers’ decisions about next year’s premiums and where they will offer health plans hinge on the verdict.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) repeatedly asked Price if he would commit to making subsidy payments, but Price refused to answer beyond reiterating that the budget includes payments through 2018. Price said he could not elaborate because he is the defendant in a lawsuit regarding these subsidies — a still-pending case brought by the Republican-led House of Representatives during the Obama administration.

Democrats accused Price of doing little to stabilize the individual insurance marketplace as insurers have announced withdrawal plans. But Sen. Pat Roberts (R-Kan.) said the market was failing and it wasn’t Price’s fault.

“We are in the Obama car and it’s like being in the same car as Thelma and Louise going into the canyon,” he said. “We need to get out of the car.”

Price was also asked about a draft rule from HHS that would scale back the ACA’s mandate requiring nearly all employers to offer health insurance covering birth control. The HHS proposal would allow more types of employers to claim moral or religious exemptions to the mandate. “I think that for women who desire birth control, it should be available,” Price said.

When Sen. Maria Cantwell (D-Wash.) pressed him to answer whether birth control should be available to women through their employers, Price reiterated that it should be available to women who want it.

“This is a very big problem,” she said. ”Women cannot be discriminated against by their employers who want to cherry-pick women’s health.”

Correction: This story was updated on June 9 to correct the day of hearing.