[UPDATED on March 6]

DENVER — When Brittany Pettersen, a Colorado state senator, gave birth to a boy in January, she became only the second lawmaker in the state to have a baby during a legislative season.

The first, Sen. Barbara Holme, delivered just two days before lawmakers adjourned nearly 40 years ago. But because she was part of a Democratic minority at the time, no one worried much about the votes Holme was missing, much less her need for paid maternity leave.

“That was the year I was born,” said Pettersen, also a Democrat. “Unfortunately, we haven’t come very far from 1981.”

Despite the inroads women have made entering the workforce and politics, paid family and medical leave remains a heavy lift in Colorado and across much of the country. For each of the past six years, the Colorado legislature has considered bills to establish a statewide paid leave program, but none have passed. Yet this year, with a Democratic governor, Democratic control of both the state House and Senate, plus more female legislators than ever before, many thought it would be the best chance for a paid leave bill in the 30 years since Holme had her baby.

Pettersen has become something of a poster child — perhaps, a poster mom — for this year’s legislative push. While undoubtedly many male lawmakers have had children while serving, her fellow senators may find Pettersen’s example hard to ignore if a paid leave bill comes to the floor.

“This is our opportunity to help Coloradans. And we’re going through it, even in our workplace,” said Pettersen, who took one month of paid leave from her legislative work. (Colorado legislators are allowed to take up to 40 days of fully compensated leave, but their salary is reduced if they’re out longer for anything other than a medical illness.)

Still, even after a bipartisan task force came to broad consensus this year for a mandatory paid family leave benefit run by the state and funded through payroll taxes, Coloradans may have to settle for something far less ambitious if anything passes at all. The fight illustrates just how divisive paid family leave can be when determining how to pay for it.

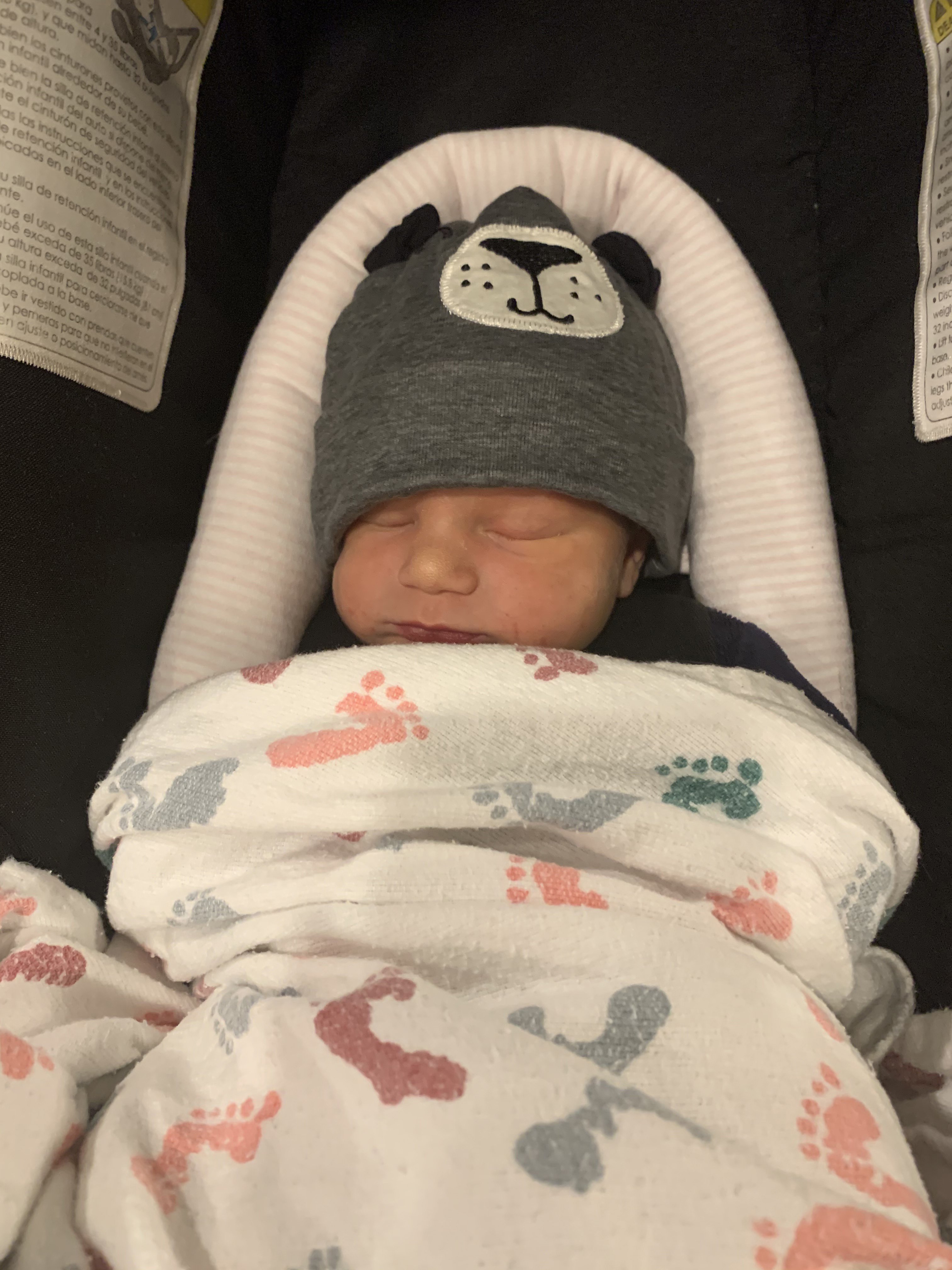

Colorado lawmaker Brittany Pettersen has pledged to bring her son, Davis, to the chamber floor for a crucial vote on paid family and medical leave, a tangible display of what’s at stake.(Courtesy of Brittany Pettersen)

Legislative Hurdles

Under federal law, employers with 50 or more employees are required to grant workers time off to deal with family or medical issues, including the birth of a child or the care of an aging parent. But companies are not required to pay workers for that time off.

Many of the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates have backed paid leave, and President Donald Trump’s budget envisioned a paid family leave program. Congress is now considering the Family and Medical Insurance Leave Act, which would provide workers up to 12 weeks of partial income for family leave regardless of the company’s size, funded through a payroll tax of 2 cents per $10 in wages. Congress passed a bill last year that will grant 12 weeks of paid family leave to federal employees beginning in October.

Some states have sought to fill the gaps and, so far, eight states — California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington — along with the District of Columbia have established paid family leave programs, funded through payroll taxes. For a while, at least, Colorado looked poised to join them.

Colorado Republicans have killed paid leave bills in years past. But last year, when Democrats took control, paid leave looked like a possibility.

“That’s also when all the details really started to matter,” said Kathy White, deputy director of the Colorado Fiscal Institute, a nonprofit research and policy advocacy organization, which backed a paid leave benefit.

As a result, the 2019 paid leave bill was the most lobbied legislation in Colorado that session, according to backers, with more than 200 lobbyists registered as working on it. But, ultimately, lawmakers were unable to come to an agreement and instead established a task force to study the issue.

A Broad Consensus

The 13-member bipartisan panel spent months poring through examples from other states and studies that looked at the costs and benefits of providing family and medical leave. They reviewed more than 1,000 public comments submitted in just 30 days.

In January, the task force issued its final recommendations with broad consensus among its members. It backed what’s called a state-run social insurance model to levy a small payroll tax to cover the paychecks of those taking paid leave.

“This has become a really big issue because the research is becoming so clear,” White said. “We can see the difference between those who have leave and those who don’t have leave or have to take unpaid leave for caregiving needs.”

A state-commissioned review found strong evidence that paid leave decreased infant mortality by 10% to 13%, increased the rate of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months, increased childhood immunization rates and improved maternal mental health.

But the task force recommendations were met with objections from various lawmakers, as well as Gov. Jared Polis. He had asked the task force to consider paid leave models other than a state-run program.

Some opposed the new payroll taxes, while others were concerned about the state’s potential costs if payroll taxes don’t collect enough. Critics have argued that paid leave mandates offer employers little flexibility to meet an employee’s specific needs — and can create an economic burden for businesses.

When Brittany Pettersen, a Colorado state senator, gave birth to her son, Davis, near the start of her state’s four-month legislative session, it highlighted the lack of comprehensive paid family leave. A bill to add a statewide system that once seemed a sure thing is getting bogged down.(Courtesy of Brittany Pettersen)

By February, bill sponsors had shifted to a compromise that would require companies to offer paid family and medical time off but would leave it up to employers to determine how to provide that.

It’s not nearly the benefit that paid-leave advocates had hoped for.

“I would have preferred a social insurance plan,” said Democratic Sen. Faith Winter, the bill’s lead sponsor. “Ultimately, you could have a perfect bill that doesn’t pass, or you could have a good bill that passes.”

Waning Support

Now it’s unclear whether the compromise bill has given up too much ground to pass. Already, two of Winter’s Democratic co-sponsors have dropped their names from the revised bill, calling into question whether it will have enough votes.

“It’s a big program with lots of details, and it impacts every person in the state,” Winter said. “When you start moving things that affect everyone and every business, that means everyone cares.”

The coalition of nonprofits and advocacy groups pushing for paid family and medical leave does have a backstop. Early this year, proponents registered two paid leave ballot measures for the November elections.

“Colorado families overwhelmingly want and expect the legislature to move forward with a plan to provide family and medical leave this year,” said Lynea Hansen, a spokesperson for Colorado Families First, a nonprofit that has been lobbying in favor of a paid leave bill. “If the legislature is unsuccessful at passing a comprehensive policy, we plan to take this initiative to the voters.”

It’s unknown whether the backers of the ballot measure would continue to press the issue if the legislature passes the compromise bill instead of the full state-run benefit advocates sought.

“What happens if the legislature does do something and it’s still not good enough for the advocates?” asked Loren Furman, senior vice president of state and federal relations for the Colorado Chamber of Commerce, which has been supportive of a paid leave bill. “Are they then going to continue down the path of the ballot initiative?”

If nothing else, the additional time it took to rework the bill has allowed Pettersen to be back from her one-month maternity leave in time for debate on the bill. The Democrats hold a slim 19-16 margin in the Senate and cannot count on a strict party-line vote because some party members are wavering in their support for the new approach.

Pettersen has pledged to bring her infant son, Davis, to the chamber floor for the crucial vote — a tangible display of what’s at stake.

“It’s just another reminder,” she said. “There are numerous moms that have been elected. But absolutely, having the experience of someone going through it right now is going to impact what we’re talking about.”

[Correction: This story was last revised at 8:38 p.m. ET on March 6 to correct a math error on how long it had been since a Colorado legislator gave birth during a legislative season before Sen. Brittany Pettersen had a son this winter. The first birth was nearly 40 years ago.]