STONE MOUNTAIN, Ga. – – At Oakhurst Medical Center, just 20 percent of kids have received all their recommended immunizations by age 2.

Adults don’t fare much better at this community health center, which provides primary care to 14,000 mostly poor people in a town famous for its granite monolith and “Confederate Mount Rushmore,” just east of Atlanta.

Less than half of the diabetics and a little more than a third of those with high blood pressure had their conditions under control in 2010 — far below national averages for the entire adult U.S. population, the latest federal data show.

“We can do better,” says Oakhurst Chief Executive Officer Jeffrey Taylor, who ticks off some of his challenges: high obesity rates; many African immigrants unaccustomed to seeking vaccinations and other preventive care, and 40 percent of patients without health insurance.

While Oakhurst is an extreme example, hundreds of the nation’s nearly 1,200 federally funded community health centers fall short on key quality of care measures, according to federal data analyzed by KHN and USA Today. The centers’ performance most often lagged national averages on helping diabetics keep their blood sugar under control and screening women for cervical cancer.

20 Million Patients Seen

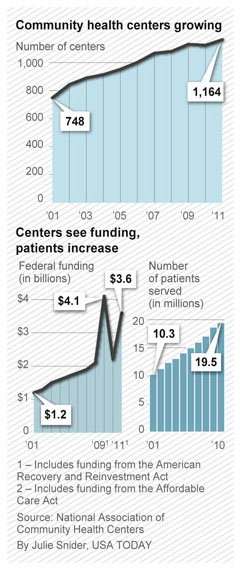

After doubling the number of patients served in the past decade to more than 20 million people a year, the mostly privately run, nonprofit centers are coming under increased pressure as they gear up for a major expansion under the health care law. Beginning in 2014, about 30 million Americans are expected to gain health coverage, half through Medicaid, the state-federal insurance program for the poor. Congress authorized $10 billion to expand the centers’ capacity on the assumption many of the newly covered would seek care there.

Since 2008, they have also been required to report data to the federal government on six performance measures, including how well they care for their patients with diabetes and high blood pressure, screening rates for cervical cancer, vaccination rates for children, provision of timely prenatal care and rates of low birth-weight babies.

A KHN-USA Today analysis of the 2010 health center data, obtained through the U.S. Freedom of Information Act, shows the level of care varies widely, including by region: Centers in the South generally perform worse than those in New England, the Midwest and California.

The analysis also found that:

— Nearly 75 percent of centers performed significantly worse — at least 10 percent below the national average for the entire U.S. population — for cervical cancer screening rates. While 75 percent of U.S. women had at least one Pap test for cervical cancer in the past three years, the average was 58 percent for women in community health centers, according to federal data.

–About 73 percent performed significantly below average in helping diabetics maintain their blood sugar levels.

— About 28 percent of centers performed significantly below average for immunizing 2-year-olds.

— Georgia was the only state to rank near the bottom on four of the six quality measures.

— Four other states — Louisiana, Virginia, Kansas and Kentucky — ranked near the bottom for three measures.

“Of course this raises a concern for us,” says Cindy Zeldin, executive director of Georgians for a Healthy Future, an Atlanta-based consumer health advocacy group. “We have so many uninsured for whom the community health centers are one of the few places where they can go for primary care.”

Still, Zeldin says she is not surprised that patients at Georgia’s 27 health centers fare worse given the state’s high rates of obesity and diabetes.

Feds Defend Quality

Federal officials point out that patients at the nation’s community health centers sometimes get better care.

For example, three out of four centers performed significantly better than the national average in helping hypertensive patients keep their blood pressure under control and more than four in 10 do significantly better at making sure women get timely prenatal care.

“We feel good about quality overall, but there is clearly room to improve,” says Jim Macrae, who oversees the centers for the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

Fewer than 20 centers show a pattern of poor performance, he says. The agency would not name them.

Oakhurst was one of eight community health centers nationwide whose patients fell below the U.S. average for all six quality care indicators in 2010. Sixty-one centers fell short on at least five indicators.

But there are bright spots even in Georgia: Albany Area Primary Health Care, a center with 11 clinic sites in south Georgia, keeps more than 80 percent of its diabetics’ blood sugar under control, which beats the rates in most community health centers.

Elizabeth Rayes, 38, of Warner Robins, Ga., credits a nurse at the center for counseling her how to control her diabetes even though she can’t afford a blood glucose meter to test herself. “They do a great job,” she says.

More Difficult-To-Treat Patients

Macrae notes the centers face greater challenges than the average doctor’s office because their patients are nearly six times as likely to be poor, two-and-a-half times as likely to be uninsured, and nearly three times as likely to be enrolled in Medicaid.

Those that treat large numbers of migrant workers and the homeless also tend to have worse outcomes because their patients face more challenges.

Some of the data reflect real problems with patient care, while others simply relate to challenges collecting information, Macrae says. For example, many health centers including Oakhurst have lower Pap test rates because women see gynecologists in other settings, he says.

One factor making it difficult to compare centers’ performance is that the federal data are not risk-adjusted to account for the fact that some centers treat sicker patients.

Nonetheless, the report cards are motivating centers to improve, Macrae says. “We are asking for more transparency to help drive better performance,” he says, adding that all centers should be performing at the levels of top facilities.

Dr. David Stevens, medical director of the National Association of Community Health Centers, the industry’s main trade group, says the data show most centers are providing good care – and that they are more accountable than private medical practices which do not report quality data to the government.

Quality Varies Within Cities

Still, quality of care varied not only by state and region, but also among facilities in the same city. In Milwaukee, 16th Street Community Health Center beat U.S. averages for all six quality indicators. Nearby Milwaukee Health Services was below average for five of six measures.

“There is tremendous performance variation within community health centers and also tremendous variation among any health providers, hospitals, nursing homes, doctors,” says Deborah Gurewich, a Brandeis University researcher. “That’s the American health system.”

A study Gurewich authored in 2011 in the Journal of Ambulatory Care Management also found wide variation in health center performance in avoiding preventable hospital admissions for Medicaid patients.

Lower-performing centers typically have a higher proportion of uninsured patients and more staff turnover, she says. Conversely, centers that have electronic health records tend to have higher performance. About half of all centers are using electronic health records. Those report quality data for all their patients to the federal government. The rest report on a sample of their data.

Data Not Used As ‘Gotcha’

The Obama administration this year will begin reducing Medicare payments to hospitals for falling short on some quality care indicators such as infection rates, but it has no plans to do that with the health centers. “We don’t want to use the data as a ‘gotcha’,” Macrae says. “We want to use it for performance improvement.”

This year, the government has begun collecting additional quality information, including whether the centers ask if patients smoke, provide counseling to overweight patients and prescribe appropriate medications to those with asthma.

Until now, most health centers shared their quality data only with the local board of directors, the majority of whom must be regular patients. But the agency plans to publish 2011 data on the individual centers on its website this summer.

Candy Armstead, 36, who has been coming to Oakhurst for three years, illustrates the challenge. Despite her doctor’s recommendation, she refuses to take any blood pressure medicine after a bad experience with one drug.

“It caused my hair to shed so I stopped taking it,” says Armstead, who is on Medicaid like nearly half of the center’s patients.

Taylor says his center’s performance led to pointed questions to the center’s doctors and nurses about immunization rates and other measures.

Parents are now asked about getting their children immunized, no matter why they come to the center. The same goes for women who are due for a Pap test. And an electronic health records system is being installed, which will help monitor patients.

But it continues to be an uphill battle.

Last year, Oakhurst called more than 300 patients considered at high risk because they are obese, diabetic or have high blood pressure and asked them to enroll in a free nutrition class. Only 18 signed up.

Next: Rural Georgia Center Relies on Educators, Electronic Records To Boost Patients’ Health