The ulcer on Vincent Adderly’s right foot started as a small lesion on the tip of his big toe — a minor injury for many but a serious medical risk for a diabetic.

For Adderly, 46 and uninsured, the lesion meant trips to the emergency room and hours-long waits for a doctor to scrape the wound, bandage it and send him home with a prescription for antibiotics that Adderly said he could not afford.

But two trips to the ER later, the foot ulcer hadn’t healed and had become more painful. In late May, he went to a different ER. This time, doctors at Memorial Hospital West in Pembroke Pines gave him a grim choice: have the toe partially amputated to prevent a bone infection from spreading, or treat the wound with extended antibiotic therapy and hope for the best.

Adderly chose the amputation, a decision that put him on the front lines of a fight raging in Tallahassee this week over Medicaid expansion. If Medicaid were expanded in Florida — as provided for in the Affordable Care Act, but opposed by many Republicans — Adderly would likely qualify. And if he’d had the regular medical care Medicaid can provide, he and some of his doctors believe he might have avoided the amputation.

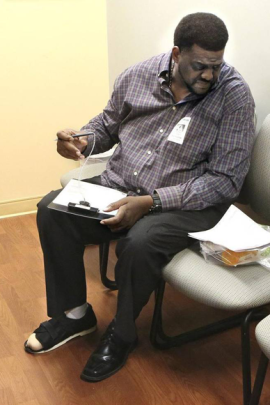

Vincent Adderly, 46, of Miami Gardens fills out forms in the medical records office at Memorial Hospital West in Pembroke Pines on Thursday, May 28, 2015. He is uninsured and diabetic and was at the hospital following his week- long hospitalization there. Part of the big toe on Adderly’s right foot had to be amputated. (Photo by Marsha Halper/Miami Herald)

“I’m evidence of time wasted,” said Adderly, who falls into a healthcare no-man’s-land that policy analysts call the coverage gap. “This could have been avoided.”

Unemployed since 2008, the Miami Gardens man said chronic back pain from a car accident and spinal fusion, along with diabetes-related complications, have left him unable to work. He earns no income and does not qualify for financial aid to buy health insurance under the ACA, or Obamacare. Because he has no dependent children and is not legally disabled, Adderly also is ineligible for Medicaid in Florida — one of 21 states that have not adopted an expansion plan.

Adderly is among an estimated 850,000 Florida adults, including about 140,000 in Miami-Dade and 80,000 in Broward, who would be newly eligible for Medicaid if the state were to adopt an expansion plan, according to the Urban Institute, a health policy research nonprofit group.

Caught in the coverage gap, Adderly said he has applied for Social Security Disability, which would make him eligible for Medicaid. But he also wants to commit his energies to advocating for Medicaid expansion — a choice that Florida’s Legislature has turned down twice already, in 2013 and 2014. The Legislature reconvened Monday in a special, 20-day session to pass a budget. The process broke down this spring over the issue of Medicaid expansion: the Senate offered a plan to help the uninsured that House leaders and Gov. Rick Scott oppose.

“This special session needs to be a session where they address people who have problems, like myself,” said Adderly, who has enrolled in civic engagement courses through a nonprofit group that advocates for Medicaid expansion, Catalyst Miami. “Why should I have to wait on special sessions when it should have been done the first time? If I was afforded the opportunity with Medicaid, or some type of insurance that Obamacare provides, I would have been able to go to a doctor.”

Kissinger Goldman, the emergency room doctor who first saw Adderly at Memorial Hospital West in late May, said there’s plenty of medical evidence that diabetics have better health outcomes when they receive regular care.

“The only way to do that,’’ he said, “is to see a primary doctor who is on top of you, who reminds you to take your medicine, who reminds you to take care of your feet, who reminds you to eat properly.’’

He said that preventive care, the kind emphasized under the ACA, could have helped a patient like Adderly avoid amputation.

“I see what happens when you don’t get preventive care,’’ he said. “You come to me in the emergency room.’’

Florida Rep. Carlos Trujillo, a Miami Republican, said there is no question that Adderly would have benefited from regular visits with a physician.

Trujillo, who opposes healthcare expansion under the ACA, said he also agrees that Adderly would have been better off with Medicaid than being uninsured. But he says those aren’t the questions dividing the Legislature.

“The question we’re debating in Tallahassee,’’ he said, “is whether Medicaid is the solution, and is it the responsibility of the state to offer insurance to individuals who have never been subsidized for insurance? … And if we do, where do we take the money from? Do we take it from education? Do we take it from transportation?

“There is a cost,’’ he said.

Under the ACA, Medicaid expansion was supposed to bridge the gap between the poorest Americans and those who make enough to qualify for government-subsidized plans. But the Supreme Court’s decision to make Medicaid expansion optional meant that Florida and 20 other mostly Republican-led states chose not to expand the state-federal insurance program for the poor.

For states that chose to expand eligibility for Medicaid, the health law requires the federal government to pay 100 percent of the cost of the newly eligible population through 2016, and never less than 90 percent thereafter.

According to advocacy groups and some state legislators, including Sen. Rene Garcia, a Hialeah Republican, Florida would receive an estimated $50 billion in federal funding to expand Medicaid.

Trujillo, however, argues that Florida’s Medicaid costs have grown dramatically over the years, and that the program now accounts for “34 percent” of the state budget. But that percentage includes both federal and state dollars. In 2014, that broke down to about $14 billion from the federal government and and about $9.5 billion from the state.

Vincent Adderly, right, a 46- year-old Miami Gardens man who is uninsured and diabetic, walks past an employee at Memorial Hospital West in Pembroke Pines on Thursday, May 28, 2015. (Photo by Marsha Halper/Miami Herald)

Still, Trujillo said, uninsured Floridians such as Adderly need access to healthcare — but not necessarily Medicaid.

“What’s the best way to get him access? For us, it’s fighting — for transparency, for expansion of scope, for reduced costs — so Vincent can buy good, quality, affordable healthcare rather than end up on Medicaid,’’ he said. “Or is the solution to expand Medicaid and put people on these programs that not you or I could tell them if they would have a better outcome? It’s 100 percent speculation.”

For Adderly, though, there is no guesswork about his need for regular medical care. There is only uncertainty about how to get there, and an urgency to act while there’s still a chance in the Legislature.

“I’m feeling concerned,” Adderly said of the chances for Medicaid expansion in Florida. “But I’m even more determined to make this happen in Florida because there’s no more time to waste. … I’m an example of what happens when you wait.”