FORT SCOTT, Kan. — A slight drizzle had begun in the gray December sky outside Community Christian Church as Reta Baker, president of the local hospital, stepped through the doors to join a weekly morning coffee organized by Fort Scott’s chamber of commerce.

The town manager was there, along with the franchisee of the local McDonald’s, an insurance agency owner and the receptionist from the big auto sales lot. Baker, who grew up on a farm south of town, knew them all.

Still, she paused in the doorway with her chin up to take in the scene. Then, lowering her voice, she admitted: “Nobody talked to me after the announcement.”

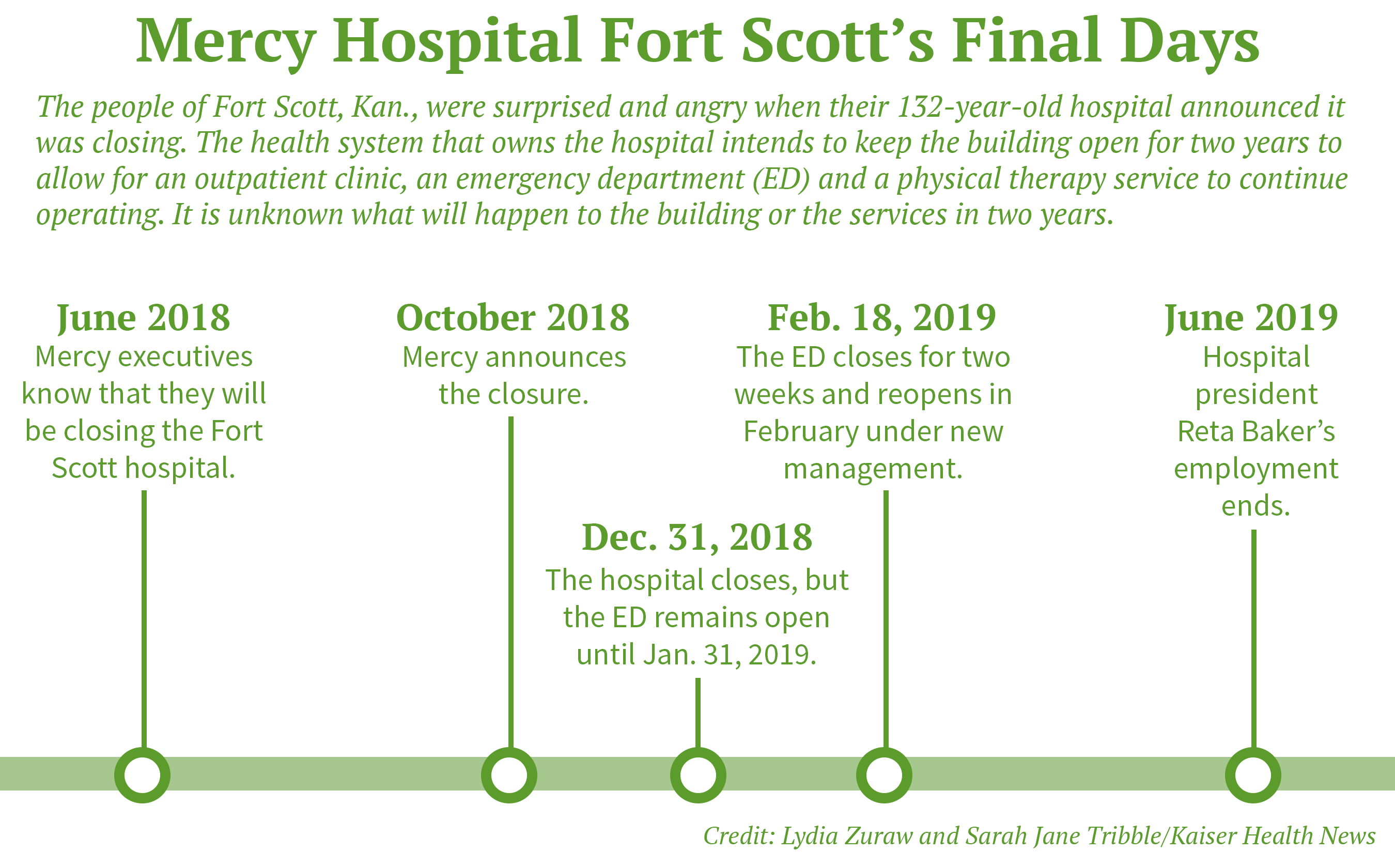

Just a few months before, Baker — joining with the hospital’s owner, St. Louis-based Mercy — announced the 132-year-old hospital would close. Baker carefully orchestrated face-to-face meetings with doctors, nurses, city leaders and staff members in the final days of September and on Oct. 1. Afterward, she sent written notices to the staff and local newspaper.

For the 7,800 people of Fort Scott, about 90 miles south of Kansas City, the hospital’s closure was a loss they never imagined possible, sparking anger and fear.

Reta Baker, president of Mercy Hospital, began as a staff nurse in 1981 and “has been here ever since.” The hospital closed at the end of 2018.(Christopher Smith for KHN)

“Babies are going to be dying,” said longtime resident Darlene Doherty, who was at the coffee. “This is a disaster.”

Bourbon County Sheriff Bill Martin stopped before leaving the gathering to say the closure has “a dark side.” And Dusty Drake, the lead minister at Community Christian Church, diplomatically said people have “lots of questions,” adding that members of his congregation will lose their jobs.

Yet, even as this town deals with the trauma of losing a beloved institution, deeper national questions underlie the struggle: Do small communities like this one need a traditional hospital at all? And, if not, what health care do they need?

Sisters of Mercy nuns first opened Fort Scott’s 10-bed frontier hospital in 1886 — a time when traveling 30 miles to see a doctor was unfathomable and when most medical treatments were so primitive they could be dispensed almost anywhere.

Now, driving the four-lane highway north to Kansas City or crossing the state line to Joplin, Mo., is a day trip that includes shopping and a stop at your favorite restaurant. The bigger hospitals there offer the latest sophisticated treatments and equipment.

Visitors to Mercy Hospital Fort Scott would pass a tall white cross as they drove down a winding driveway before arriving at the front door. Sisters of Mercy nuns founded the hospital in 1886, and the newest building, constructed in 2002, honors that Roman Catholic faith with various fixtures and stained-glass windows.(Christopher Smith for KHN)

Mercy flew its flags at half-staff in December in honor of former President George H.W. Bush, who died Nov. 30. (Christopher Smith for KHN)

And when patients here get sick, many simply go elsewhere. An average of nine patients stayed in Mercy Hospital Fort Scott’s more than 40 beds each day from July 2017 through June 2018. And these numbers are not uncommon: Forty-five Kansas hospitals report an average daily census of fewer than two patients.

James Cosgrove, who directed a recent U.S. Government Accountability Office study about rural hospital closures, said the nation needs a better understanding of what the closures mean to the health of people in rural America, where the burden of disease — from diabetes to cancer — is often greater than in urban areas.

What happens when a 70-year-old grandfather falls on ice and must choose between staying home and driving to the closest emergency department, 30 miles away? Where does the sheriff’s deputy who picks up an injured suspect take his charge for medical clearance before going to jail? And how does a young mother whose toddler fell against the coffee table and now has a gaping head wound cope?

There is also the economic question of how the hospital closure will affect the town’s demographic makeup since, as is often the case in rural America, Fort Scott’s hospital is a primary source of well-paying jobs and attracts professionals to the community.

The GAO plans to complete a follow-up study later this year on the fallout from rural hospital closures. “We want to know more,” Cosgrove said. The report was originally requested in 2017 by then-Sen. Claire McCaskill (D-Mo.) and then-Rep. Tim Walz (D-Minn.), and has been picked up by Sen. Gary Peters (D-Mich.). Here in Fort Scott, the questions are being answered — painfully — in real time.

At the end of December, Mercy closed Fort Scott’s hospital but decided to keep the building open to lease portions to house an emergency department, outpatient clinic and other services.

Mercy Hospital Fort Scott joined a growing list of more than 100 rural hospitals that have closed nationwide since 2010, according to data from the University of North Carolina’s Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research. How the town copes is a window into what comes next.

An empty operating room at the closed hospital(Christopher Smith for KHN)

Unused hospital equipment is stored for shipment to other hospitals in the nonprofit Mercy health system.(Christopher Smith for KHN)

While some parts of the building are still in use, vast, empty halls and workstations abound at Mercy’s closed Fort Scott hospital. (Christopher Smith for KHN)

‘We Were Naive’

Over time, Mercy became so much a part of the community that parents expected to see the hospital’s ambulance standing guard at the high school’s Friday night football games.

Mercy’s name was seemingly everywhere, actively promoting population health initiatives by working with the school district to lower children’s obesity rates as well as local employers on diabetes prevention and healthy eating programs — worthy but, often, not revenue generators for the hospital.

“You cannot take for granted that your hospital is as committed to your community as you are,” said Fort Scott City Manager Dave Martin. “We were naive.”

Indeed, in 2002 when Mercy decided to build the then-69-bed hospital, residents raised $1 million out of their own pockets for construction. Another million was given by residents to the hospital’s foundation for upgrading and replacing the hospital’s equipment.

“Nobody donated to Mercy just for it to be Mercy’s,” said Bill Brittain, a former city and county commissioner. The point was to have a hospital for Fort Scott.

Today Mercy is a major health care conglomerate, with more than 40 acute care and specialty hospitals, as well as 900 physician practices and outpatient facilities. Fort Scott is the second Kansas hospital Mercy has closed.

Tom Mathews, vice president of finance for Mercy’s southwestern Missouri and Kansas region, said Fort Scott’s steady decline in patients, combined with lack of reimbursement — as well as the increasing cost of expenses such as drugs and salaries — “created an unsustainable situation for the ministry.”

But Fort Scott is a place that needs health care: One out of every four children in Bourbon County live in poverty. People die much younger here than the rest of the state and rates for teen births, adult smoking, unemployment and violent crime are all higher in Bourbon County than the state average, according to data collected by the Kansas Health Institute and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Ten percent of Bourbon County’s more than 14,000 residents, about half of whom live in Fort Scott, lack health insurance. Kansas is one of 14 states that have not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and, while many factors cause a rural closing, the GAO report found states that had expanded Medicaid had fewer closures.

Dr. Katrina Burke checks Randall Phillips during an exam at Mercy Hospital in Fort Scott, Kan., in December. “Up in the city, a lot of doctors don’t do everything like we do,” Burke says of the variety of patients she sees as a family practice doctor who also delivers babies. (Christopher Smith for KHN)

Burke, a family practice physician, also delivered babies at Mercy Hospital before it closed. “A lot of my moms are single moms … they don’t have good resources to even get to their OB appointment,” says Burke, who adds that she’s worried about how her patients will get to another hospital 30 miles away when it’s time for the baby to come. Burke delivered 85 babies last year. (Christopher Smith for KHN)

The GAO report also found that residents of rural areas generally have lower household incomes than their counterparts in bigger cities, and are more likely to have limitations because of chronic health conditions, like high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity, that affect their daily activities.

The county’s premature birth rate is also higher than the 9.9% nationwide, a number that worries Dr. Katrina Burke, a local family care doctor who also delivers babies. “Some of my patients don’t have cars,” she said, “or they have one car and their husband or boyfriend is out working with the car.”

By nearly any social and economic measure, southeastern Kansas is “arguably the most troubled part of the entire state,” said Dr. Gianfranco Pezzino, senior fellow at the Kansas Health Institute. While the health needs are great, it’s not clear how to pay for them.

Health Care’s ‘Very Startling’ Evolution

Reta Baker describes the farm she grew up on, south of town, as “a little wide place in the road.” She applied to the Mercy school of nursing in 1974, left after getting married and came back in 1981 to take a job as staff nurse at the hospital. She has “been here ever since,” 37 years — the past decade as the hospital president.

It has been “very startling” to watch the way health care has evolved, Baker said. Patients once stayed in the hospital for weeks after surgery and now, she said, “they come in and they have their gallbladder out and go home the same day.”

With that, payments and reimbursement practices from government and health insurers changed too, valuing procedures rather than time spent in the hospital. Rural hospitals nationwide have struggled under that formula, the GAO report found.

Acknowledging the challenge, the federal government established some programs to help hospitals that serve poorer populations survive: Through a program called 340B, some hospitals get reduced prices on expensive drugs. Rural hospitals that qualified for a “critical access” designation because of their remote locations got higher payments for some long stays. About 3,000 hospitals nationwide get federal “disproportionate share payments” to reflect the fact that their patients tend to have poor or no insurance.

Fort Scott took part in the 340B discount drug program as well as the disproportionate share payments. But, though Baker tried, it could not gain critical access status.

When Medicare reimbursement dropped 2% because of sequestration after the Budget Control Act of 2011, it proved traumatic, since the federal insurer was a major source of income and, for many rural hospitals, the best payer.

Then, in 2013, when the federal government began financially penalizing most hospitals for having too many patients returning within 30 days, hospitals like Fort Scott’s lost thousands of dollars in one year. It contributed to Fort Scott’s “financial fall,” Baker said.

Baker did her best to set things right. To reduce the number of bounce-back admissions, patients would get a call from the physician’s office within 72 hours of their hospital stay to schedule an office visit within two weeks. “We worked really, really hard,” Baker said. Five years ago, the number of patients returning to Fort Scott’s hospital was 21%; in 2018 it was 5.5%.

Meanwhile, patients were also “out-migrating” and choosing to go to Ascension Via Christi in Pittsburg — which is two times larger than Fort Scott — because it offered cardiology and orthopedic services, Baker said. Patients also frequently drove 90 miles north to the Kansas City area for specialty care and the children’s hospital.

“Anybody who is having a big surgery done, a bowel resection or a mastectomy, they want to go where people do it all the time,” Baker said. Mercy’s Fort Scott hospital had no cardiologists and only two surgeons doing less complicated procedures, such as hernia repair or removing an appendix.

Last year, only 13% of the people in Bourbon County and the surrounding area who needed hospital care chose to stay in Fort Scott, according to industry data shared by Baker.

There were no patients in the hospital’s beds during one weekend in December, Baker said, adding: “I look at the report every day. It bounces between zero and seven.” The hospital employed 500 to 600 people a decade ago, but by the time the closure was announced fewer than 300 were left.

Fort Scott City Manager Dave Martin stands in the middle of the city’s historical main street, which connects to one of the first military outposts built in the United States. Martin, who feels angry at Mercy for abandoning the community, says, “We really thought that we had a relationship.”(Christopher Smith for KHN)

That logic — the financial need — for the closing didn’t sit well with residents, and Mercy executives knew it. They knew in June they would be closing Fort Scott but waited until October to announce it to the staff and the city. City Manager Martin responded by quickly assembling a health task force, insisting it was “critical” to send the right message about the closure.

Relations between Mercy and the city grew so tense that attorneys were needed just to talk to Mercy. In all, Fort Scott had spent more than $7,500 on Mercy Closure Project legal fees by the end of 2018, according to city records.

Will Fort Scott Sink With No Mercy?

When Darlene Doherty graduated from Fort Scott High School in 1962, there were two things to do in town: “Work at Mercy or work at Western Insurance.” The insurance company, though, was sold in the 1980s, and the employer disappeared, along with nearly a thousand jobs.

Yet, even as the community’s population slowly declined, Martin and other community leaders have kept Fort Scott vibrant. There’s the new Smallville CrossFit studio, which Martin attends; a new microbrewery; two new gas stations; a Sleep Inn hotel, an assisted living center; and a Dairy Queen franchise. And the McDonald’s that opened in 2012 just completed renovation.

The town’s largest employer, Peerless Architectural Windows and Doors, which provides about 400 jobs, bought 25 more acres and plans to expand. There’s state money promised to expand local highways, and Fort Scott has applied for federal grants to expand its airport.

Baker and some of the physicians on Mercy’s staff have been busy trying to ensure that essential health care services survive, too.

Baker found buyers for the hospital’s hospice, home health services and primary care clinics so they could continue operating.

Burke, the family care doctor, signed on to be part of the Community Health Center of Southeast Kansas, a federally qualified nonprofit that is taking over four health clinics operated by Mercy Hospital Fort Scott. She will have to deliver babies in Pittsburg, which is nearly 30 miles away on a mostly two-lane highway that has construction workers slowing traffic as they work to expand it to four lanes.

Burke said her practice is full, and she wants her patients to be taken care of: “If we don’t do it, who’s going to?”

Mercy donated its ambulances and transferred emergency medical staff to the county and city.

And, in a tense, last-minute save, Baker negotiated a two-year deal with Ascension Via Christi hospital in Pittsburg to operate the emergency department — which was closed for two weeks in February before reopening under the new management.

But she knows that too may be just a patch. If no buyer is found, Mercy will close the building by 2021.

This is the first installment in KHN’s year-long series, No Mercy, which follows how the closure of one beloved rural hospital disrupts a community’s health care, economy and equilibrium.